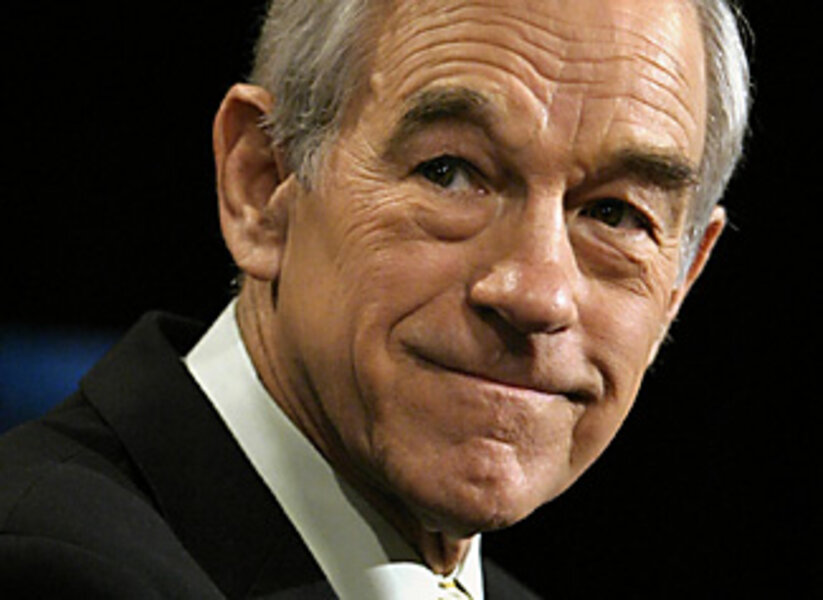

Ron Paul: an absolute faith in free markets and less government

| Berlin, N.H.

Ron Paul still looks surprised when his calls to follow the Constitution and restore a sound currency set off whoops of approval at a campaign stop.

The 10-term GOP congressman from Texas has been making these points for 30 years, with little to show for it beyond hundreds of House votes on the short end of 434 to 1. Critics called him a crank.

But lately, his views and values – the product of a lifetime of intense, self-directed study – are finding an audience. His message is basic: freedom and limited government. Repeal the welfare-warfare state. Get out of Iraq, now. Abolish the income tax. End the war on drugs. Put the dollar back on a more solid footing.

"Unlike some others, I wasn't really anxious to run for president," he tells supporters at Tea Bird's Café and Bistro in Berlin, N.H. "I didn't believe the country was ready for a strict constitutionalist."

When he says "strict," he means it. As a member of Congress, he refuses to vote for any bill not explicitly set out in the Constitution, earning him the nickname "Dr. No." He routinely votes against new taxes, deficit budgets, government surveillance, gun control, war funding, and the war on drugs. He would abolish the Internal Revenue Service, the Federal Reserve, the US Departments of Education, Energy, and Commerce as well as other "unconstitutional domestic bureaucracies." He has called for America to withdraw from the World Trade Organization and the United Nations.

At the heart of Paul's worldview is a conviction that people are born free and should govern themselves – and that free markets make better decisions than governments do.

"Some people think I don't love governing, but it's different," he says in a Monitor interview. "I believe in self-governing and family governing. The responsibility is put more on the individual than on some huge monstrosity in Washington."

Family Roots

Paul traces his values of personal responsibility and self-reliance to his early family life. His father, Howard, the son of a German immigrant, ran a family dairy business in Green Tree, Pa., near Pittsburgh, where he pasteurized and bottled milk. The third of five sons, Paul learned responsibility and the work ethic at age 5 in the family basement. There, milk bottles were washed by hand, and he and his brothers earned a penny for every dirty bottle they spotted coming down a conveyer belt.

"We learned the incentive system," he says. The boys soon figured out that one of their uncles was a worse bottle washer than the other. "We liked to work for that one uncle, because we got more pennies," he says.

The five boys shared a small bedroom in a four-room house. From spring through fall, they slept outside in a small, screened porch. His grandmother and two uncles lived in the same family compound. His father hoped that all five sons would become Lutheran ministers; two of them did. "Confirmation was a big event in my family; birthdays weren't a big event," Paul says. His mother, Margaret, urged her sons to read and get an education.

"I would say that probably from the cradle, their ethic was work and church. That was it," says Carol Paul, the candidate's wife of 50 years. "They weren't a family that played a lot. Everything was serious."

The family lived two miles from the local high school. Although there was a bus to school, Paul preferred to run. He won the state championship in the 220-yard dash and ranked No. 2 in the 440-yard run in Pennsylvania. "He knew he was obligated to do with his God-given body the best he could," says Mrs. Paul. They met in high school at a track meet and married in his last year at Gettysburg College in Gettysburg, Pa., where he studied biology.

Paul says he briefly considered becoming a Lutheran minister, but opted instead for medicine. He graduated from Duke University Medical School in Durham, N.C., in 1961, and was just starting a residency in internal medicine when he was drafted into the US Air Force. From 1963 to 1965, he served as a flight surgeon, then moved to Texas to practice obstetrics. As an OB/GYN, he has delivered more than 4,000 babies.

Paul doesn't often talk about religion, at least not in the context of a political campaign. There's a reason the Gospels teach praying in secret, he says. Over the years, he has attended an Episcopal church, which "became more liberal than we were comfortable with," as well as an evangelical church. He currently attends Baptist services.

Austrian economics

The most decisive intellectual influence in Paul's life was his discovery, while in medical school, of a passion for economics. It started with two vast novels: Ayn Rand's "Atlas Shrugged" and Boris Pasternak's "Dr. Zhivago," a gift from his mother. Both books make a case for the threat that big government bureaucracies pose to creativity and liberty.

Later, he read his way into Austrian economics – the counterweight to Keynesian economic ideas that informed the New Deal. He read Friedrich Hayek's "The Road to Serfdom" – a book that influenced a generation of American conservatives – and especially Ludwig von Mises, a libertarian who extended the influence of the Austrian school of economics in the United States.

For the Austrian school, government intervention in free markets isn't a formula for long-term economic growth. Mises warned that over time it would cripple free markets and lead to state control. Free markets are always superior to a centrally planned economy, he wrote. Mises also advocated a non-inflationary gold standard – an idea that Paul has made his own in his 2007 book "The Case for Gold" and a forthcoming book "Pillars of Prosperity: Free Markets, Honest Money, Private Property."

In 1971, Paul and another local doctor closed their practices for a day and drove 60 miles to the University of Houston to hear Mises give one of his last lectures in the United States.

"I just thought it was fascinating. It made common sense – the sort of thing I would have concluded on my own, but the Austrian economists were a lot smarter," Paul says. He made friends with American economists such as Murray Rothbard, a student of Mises, and often visited Milton Friedman while continuing his own study of economics and world markets.

"He's been a very serious student of economics since medical school, and has read a huge amount of history – constitutional history and monetary history. His philosophical and economic views drive him and everything he does," says Llewellyn Rockwell, a former congressional chief of staff for Paul. Mr. Rockwell is president of the Ludwig von Mises Institute in Auburn, Ala., and maintains the popular website, lewrockwell.com.

As a physician, Paul says he came to resent government intervention in his practice. In his years as an OB/GYN, he didn't accept Medicare and Medicaid payments because he felt they represented unconstitutional government overreach. Sometimes, he'd treat patients for free.

"I found that government was interfering with my judgment as a doctor, disrupting the doctor/patient relationship, and making prices go up," he says.

But what drove him into public life was President Richard Nixon's decision in 1971 to break the last link between gold and US currency and impose wage and price controls. "I decided to speak out," he says.

A nation that spends, borrows, and prints too much money inevitably pays a price, he says. Unrestrained by a link to gold, the Federal Reserve can create too much credit, fueling housing and stock bubbles. The result: The dollar continues to goes down in value, the nation becomes ever more dependent on borrowing money abroad, and young people pay the price. A return to the gold standard restrains the government and restores the value of the dollar.

"My influence, such as it is, comes only by educating others about the rightness of the free market," he wrote in a 1984 essay, "Mises and Austrian Economics: A Personal View."

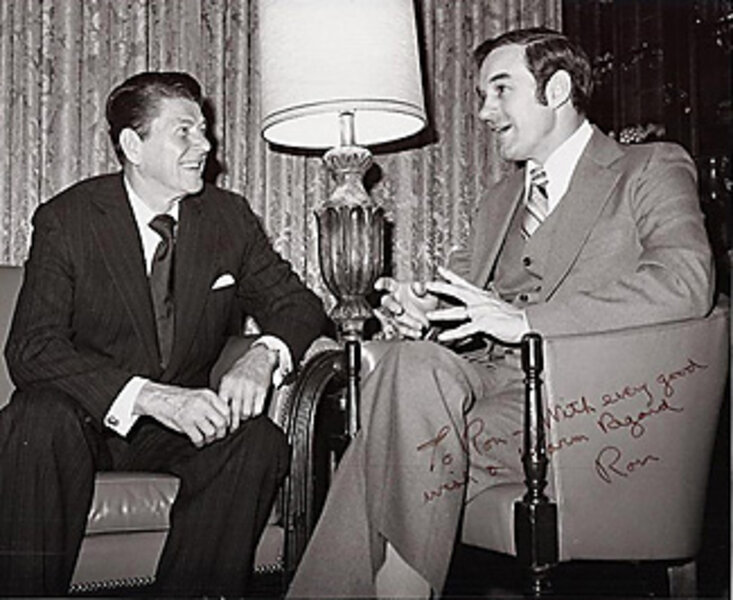

In Congress, Paul often speaks of his own record of consistency in voting against big government and refusing the perks it offers. He says he will not accept a government pension and did not seek government loans to help finance college for his five children. Paul, a longtime Ronald Reagan supporter, even voted against awarding the former president a Congressional Gold Medal in 2000, saying that taxpayers shouldn't be charged the $30,000 to mint the coin.

But critics note inconsistencies in Paul's long public record. For example, while Paul crusades against big government and voted against government funds for victims of hurricane Katrina, he has requested and won billions in special projects for his congressional district, which includes Galveston, Texas.

"I put it in because I represent people who are asking for some of their money back…. And if Congress has the responsibility to spend the money, why leave the money in the executive branch and let them spend the money?" he said on NBC's "Meet the Press" Dec. 23.

At a recent town meeting in Conway, N.H., one audience member said he supported most of Paul's positions, but wondered whether government wasn't needed after all in the cases of monster storms, such as hurricane Katrina. Paul cited the case of the 1900 hurricane in Galveston, which he said rebuilt significantly without help from Washington.

Some libertarian critics also complain that his opposition to abortion rights for women violates libertarian principles of choice. In an interview, Paul says that he came to his views on abortion in part from his experience delivering babies. "From the very beginning, I had a moral and legal obligation to take care of two people, the mother and the child, and if I did anything wrong, I realized that I could be sued for it," he said. "That had an impact on me."

He recalls witnessing an illegal abortion in his first year out of medical school that made an impression, too. "Once I became more firmly entrenched with libertarian beliefs, I realized that another life was involved, I saw this as a principle of nonaggression, which libertarians adhere to. The baby has a choice, too."

For some Washington-based libertarians, Paul's success on the campaign trail is puzzling. "Because Ron Paul is personally a very traditional man, a small town guy, his libertarianism is embedded in a lot more traditionalism that you find in many libertarians," who bristle at his stance on abortion, for example, says Brian Doherty, senior editor at Reason Magazine, the leading libertarian political and cultural journal. "But many financial analysts, who are disproportionate fans of the Paul campaign, say that in their world, the stuff that might strike a normal American as kooky, such as restoring the gold standard, does not strike them as kooky, especially given how the dollar's value is plummeting. There isn't a single other candidate out there talking about their world in an interesting way – or at all," he adds.

A surge of grass-roots support

When Paul first ran for president as the Libertarian Party candidate in 1988, he won 0.54 percent of the vote. In his second presidential bid, he's on track to do better.

While Paul still polls only in single digits nationally and in early primary states, his supporters have raised more than $19 million since October, including a record $6.2 million on one day, Dec. 16. This unofficial, grass-roots campaign is out-organizing all other campaigns over the Internet and recently launched a Ron Paul blimp.

"I'm not surprised that the views are popular, but I'm surprised to the extent that people have rallied and gotten spontaneously involved and done so much in fundraising and campaign events," Paul said in a Monitor interview.

Paul says his campaign is still working out what to do with the last quarter's surge of campaign contributions. "It's a real job figuring out what to do with it," he says. "We're going to budget it out. It just means it's a lot easier planning for super-Tuesday [on Feb. 5], when we have money in the bank."

In Iowa, the campaign has used new funds to quickly ramp up a ground operation. In New Hampshire, it launched new television and radio ads.

Some experts say polls may be undercounting Paul's support, because so many of his backers haven't voted in the past and use cellphones rather than the landlines, which pollsters use. That's why Paul "is likely to do better on election day than polls say he might," said Fergus Cullen, chairman of the New Hampshire Republican Party in an interview for C-SPAN's "Newsmakers" on Sunday.