Nonprofit slips in race for cheap laptop for world's poor kids

| Oakland, Calif.

The vision was grand: Develop a cheap laptop and get it into the hands of 150 million school children in the developing world.

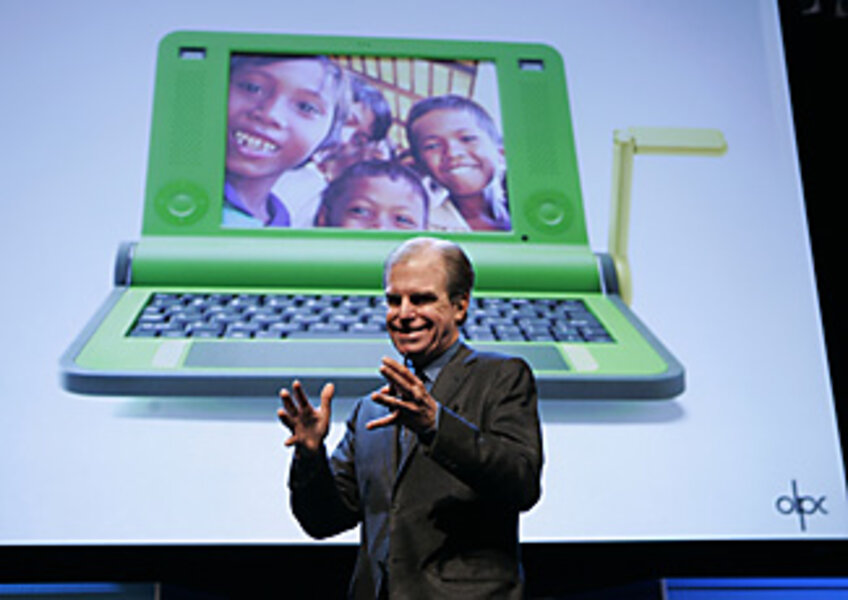

Making the computer turned out to be the easy part. On Wednesday at the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, Nicholas Negroponte, founder of One Laptop Per Child, showed off the $200 XO. The innovative computer sports a bright screen readable in sunshine and a highly efficient battery that can be recharged by cranking it.

But One Laptop has run into controversy – a corporate partner and the group's chief technology officer pulled out in recent weeks – which has experts noting perils for the broader social entrepreneur movement.

Social entrepreneurs, who aim to solve social problems using business-world principles, have tackled everything from expanding rural credit to marketing indigenous crafts in recent years. But experts say the problems at One Laptop point to a challenge for these emerging entrepreneurs. They often excel at trailblazing new markets among the world's poor but struggle to achieve large-scale sales and distribution.

"In many respects, these social entrepreneurs are pathfinders, they are like the research and development for bigger players that have otherwise ignored the bottom of the pyramid market," says James Koch, a professor at Santa Clara University in California.

For example, One Laptop's XO has proven the concept of cheap laptops. Companies like Lenovo and Intel, sensing the market potential, are now working on their own models. This isn't necessarily bad for One Laptop's ultimate goal.

"Part of our model of success is to have competition, to have other people in this space," says Walter Bender, president of software and content at One Laptop. "We don't need to be the monopoly or biggest player in the market."

But the competitors' products aren't helping One Laptop's efforts to secure big orders. So far, it has orders for 500,000 laptops, with more than 100,000 already en route to places such as Afghanistan and Haiti. But it's far behind its goal to sell 150 million units by the end of 2008.

One reason for the shortfall, One Laptop alleges, is that a former partner – Intel – was disparaging the XO as it developed its own ultra-cheap laptop, the Classmate.

"Their sales people were saying, 'Because we're on the board, we have inside info and we know that everything is broken and it doesn't work,' " says Mr. Bender.

Intel has told a different story, saying that Mr. Negroponte was unreasonably demanding that the company stop marketing the Classmate in regions targeted by One Laptop. Intel didn't respond to an interview request.

Partnerships with multinational corporations can be double-edged swords for nonprofit startups. On the one hand, they're one of the quickest ways for startups to ramp up delivery of a product. On the other hand, nonprofits and corporations have different bottom lines, which means that such partnerships need to develop slowly and carefully, says Nora Silver, director of the Center for Nonprofit and Public Leadership at the University of California, Berkeley.

A successful partnership between clothing-manufacturer Timberland and CityYear, a nationwide volunteer corps, took years to forge. The Intel partnership, however, seemed hasty and didn't integrate the sales force into the effort, Dr. Silver says.

"Did these folks have a clear contract?" she asks. "You have to be very clear about such basic agreements."

One Laptop was acting as if they had a contract with exclusivity and noncompete clauses, she adds. Bender says there was only a nondisparage agreement.

The difficulty of scaling up a business isn't limited to social entrepreneurs. For-profit startups struggle with it, too. But entrepreneurs have a bigger challenge when they target poor people, especially those who are uneducated and live in remote areas.

Traditional marketing campaigns on TV and billboards may miss these customers entirely. And putting the product on shelves may not be enough. The entrepreneurs may have to find ways to advance small loans to would-be buyers. They may have to find indigenous nonprofit groups that could open markets that a corporation would never devote the time or have the credibility to crack.

One Laptop decided to target ministries of education to get bulk orders for schools. Working with those agencies, even in the developed world, requires a lot of effort and patience, notes John Quelch, a professor at the Harvard Business School.

"One of the knocks against [One Laptop] could be that they focused very much at achieving a price point for the product, but didn't necessarily focus as much on developing a solution for the ministry of education for country X," says Dr. Quelch, adding that this can be a common pitfall.

"Initially, we had three or four people doing that around the globe, which is a stretch," says Bender. One Laptop is now working closely with Brightstar, the world's largest cellphone distributor, to help with global logistics.