Sea captains' logbooks reveal secrets of New England's fishing culture

| Durham, N.H.

In the hamlets and modest seaports that dot the coastal counties of New England, Bill Leavenworth trolls for the lost bounty of the Gulf of Maine. His prey: the bound, handwritten logs kept by the captains of virtually every fishing boat that plied those rich waters between 1852 and 1866.

The logs were once held in the region's customs houses, but over time were scattered to the four winds. Some landed in basements and attics, some were donated to local libraries and museums, and others returned to fishermen. On Nantucket Island, a number were stuffed between the walls of a public building as insulation against the winter cold, and were only recently found during a renovation. Others were undoubtledly used to start the fires of fish-house stoves or simply thrown away.

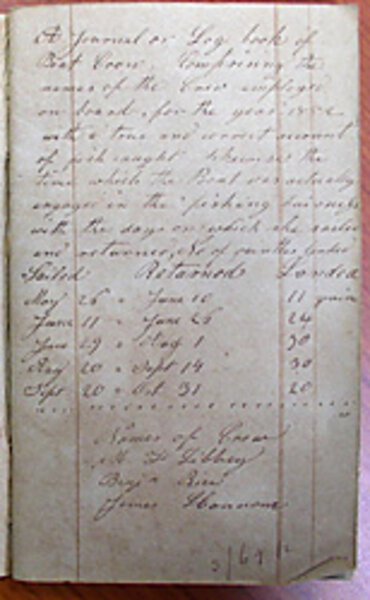

In the yellowing pages of these surviving logbooks lie the secrets of the ocean fisheries' past – and perhaps lessons for its troubled present. The books contain daily entries on the vessels' movements, the weather, unusual occurrences, and careful tallies of the number of fish caught by each man aboard. The numbers and words have yielded some bracing revelations about just how many cod there once were in New England and the Canadian Maritimes.

And so, Mr. Leavenworth, a University of New Hampshire (UNH) researcher often finds himself standing behind a lectern at churches, high schools, or libraries, describing his team's work to commercial fishermen, gentleman farmers, retirees, and small-business owners who populate the coast. "My last car had 232,000 miles on it," says Leavenworth, whose own ancestor fished off New Hampshire in the 1660s.

Every trip will end, he hopes, with the winning of one more piece – one more logbook – in a historical puzzle.

***

Three years ago, Leavenworth was giving a talk to members of the Old Berwick Historical Society in southern Maine, just up the Salmon Falls River from Portsmouth, the once-bustling seaport where New Hampshire got its start.

The presentation ended and an audience member – the Historical Society's president – came forward. "Hey, I think we've got some of those [logbooks] in our collections," she told him.

Two weeks later, Leavenworth was back in Berwick, carefully photographing the logs of the schooner William Penn and eight other vessels that once plied the Gulf of Maine from nearby Kennebunkport, their successes and failures scratched out in ink on stout linen paper.

At other talks, fishermen have come back to Leavenworth with their third great-great-great-grandfather's logs, occasionally bearing water stains from a Civil War era storm. Volunteer staff at historical societies in tiny Maine ports have helped him hook others hidden in storage rooms.

The Gulf of Maine Cod Project – which Leavenworth's work contributes to – is one of many efforts around the world that bring maritime historians and fishery scientists together to reconstruct the past and to answer the question: What was marine life like before the 20th century?

Danish researchers have been looking at monastery records, which tabulated tithes from fishing activities, while a British team is trying to reconstruct medieval cod and herring fisheries through discarded fish bones.

New Englanders' logbooks are believed to be especially accurate, because fishermen had no incentive to over- or underreport their catches. Individual fishermen were paid according to the number of fish they caught, while at the dock, the captain was paid by the weight of the catch. Combined with log entries showing where the boats fished, this data allowed researchers to calculate the distribution of fish stocks and the average size of the fish caught.

Such reconstructions of past populations can be enormously important today for fisheries managers, which is what led Andrew Rosenberg to help create the UNH project. A former deputy director of the National Marine Fisheries Service and a member of the US Commission on Ocean Policy, Mr. Rosenberg had a front row-seat during the collapse of many of New England's commercial fish populations during the 1980s and 1990s.

"An awful lot of my work ... was focused on rebuilding fisheries, and we were stuck in this box where rebuilding targets were based on the levels of the 1980s, because there was more then than there is now," recalls Mr. Rosenberg, who is now at UNH. "But we know that overfishing has occurred for a much longer period of time, and that even in the 1980s, the stock was producing nowhere near what it could."

Leavenworth's haul of logbooks shows just how far back you have to go to understand the current fishery crisis – and the true extent of the ecological damage.

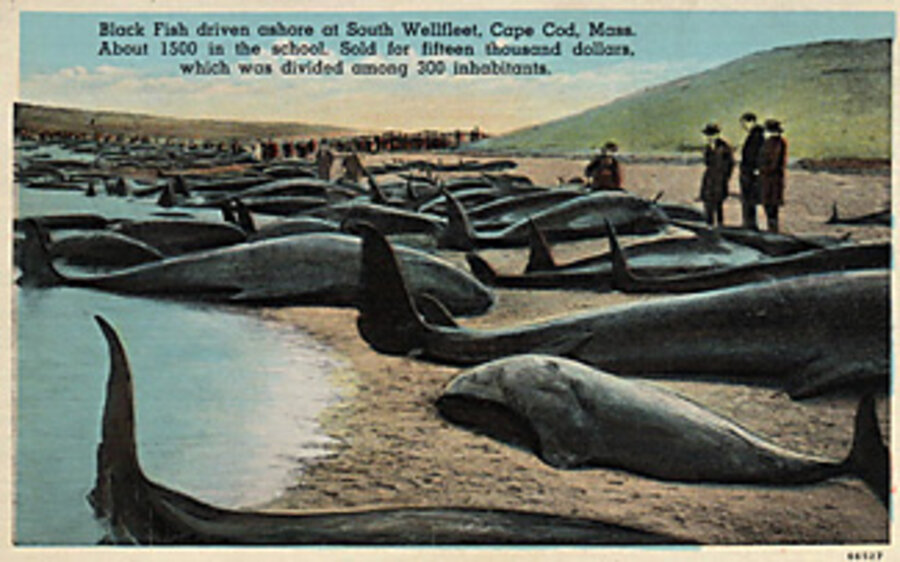

In 1855, just 43 schooners out of Beverly, Mass., were catching considerably more cod in the waters south of Nova Scotia in a season than their modern counterparts can catch today. Crews fishing over the side with baited hand lines caught 7,800 metric tons of cod – about three times what fishermen caught in that area in 2006. And they did it within sight of land in coastal waters where today cod are virtually nonexistent.

Likewise, in 1861, fishermen from a handful of Maine fishing hamlets using small sailboats and baited hand lines were able to catch more cod than were caught in the entire Gulf of Maine between 1996 and 1999 by the entire US fleet, with their powerful engines, enormous bottom trawling nets, high-tech fish finders, and satellite navigation systems.

"Ask yourself: what were [the cod] eating?" suggests W. Jeffrey Bolster, the UNH maritime historian who is part of the project. "When you think about the copepods and krill, all the way up to the alewives and mackerel that had to be present in the inshore area to feed them, it's flabbergasting. It was a totally different world out there."

***

If nature's bounty is not timeless, there may be a small consolation in knowing human nature is.

Part of the problem today, says Rosenberg, is in restraining younger fishermen who are too young to remember what fishing was like in the 1960s or 1970s. One of his colleagues was once accosted by a fishermen in his 20s who was angry that bluefin tuna quotas were going to be lowered.

"He was screaming that there were more tuna out there than he'd ever seen in his life," Rosenberg recalled. "My friend listened for a while and said, 'Well, you're not very old.' "

But even in the 1850s, older fishermen were concerned that their sons and grandsons were unaware of the extent to which the fish populations had declined.

"There were petitions from fishermen – we have zillions of them – lamenting what was happening and demanding regulations," says Mr. Bolster. "We have people from each generation saying, basically, these young guys now don't know what fishing was like when it was good."

And even back then, fishermen's warnings about the destructive power of new technology went unheeded. In the 1850s, Swampscott, Mass., hand-line fishermen begged state legislators to outlaw new long lines that used hundreds of hooks rather than one or two. They warned that otherwise cod and haddock would become as "scarce as salmon."

For researchers like Leavenworth, such stories make the hunt for logbooks more than an academic enterprise. Understanding fish population trends is important, but so is telling the vivid tales found in these aging books.

"You just tell these stories to someone and they immediately get the picture," says historian Karen Alexander, who coordinates the project. "They get in their minds what real abundance looks like and what these ecosystems can really do – and then they want that."