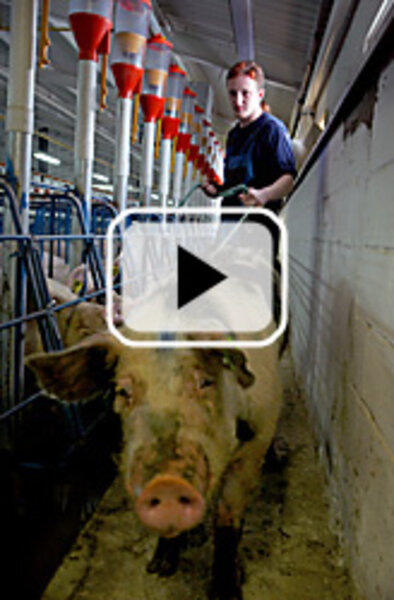

In a high-tech pig farm, rural Russians gain a foothold to a better way of life

| Zaraysk, Russia

Three hours outside Moscow, where snowy weeds bow to the bitter wind, salvation has come.

It's not pretty; in fact, it really smells. But for the 27 people who work inside the steamy barns of this new pig farm, life just got a whole lot better.

"We worked at a socialist farm before coming here. The labor conditions were zero and the salary was low," says Natalya Kuskova, a team leader who now gets five weeks of vacation to spend with her daughter. "Our farm is so wonderful; they pay for lunch … and the attitude toward us is very good; it inspires you to work."

The operation, valued at $29 million, was funded by a Spanish outfit and is expected to pay off that investment in six to seven years. It is part of a boom in agriculture across Russia, where land is 20 times cheaper than in Europe, and a two-year-old government initiative offers virtually interest-free credit to investors. One of five "national projects" implemented under President Vladimir Putin, the agriculture push is aimed at increasing production and reviving the countryside.

"I live 10 kilometers [six miles] from here – we've got neither pigs nor cows," says Tatyana Novichkov, a young employee in the farm's artificial-insemination lab. "We need investment."

But it's not easy for investors, says farm director Yevgeny Butovsky. "Bureaucracy is much more aggressive now than even five years ago," says Mr. Butovsky, whose operation is controlled by more than 50 agencies. "To respect … all the rules is just impossible."

It's also a challenge to find help, especially men – most of whom take better-paying jobs in the cities.

"You're left sometimes with the leftovers – what Moscow doesn't want," says manager Simon Oxby, a British transplant who bemoans the alcoholism and lack of education that is prevalent in the region. "It's like watching the Simpsons – Bart is very similar to Homer, while Lisa is different altogether."

For Alexander Gerasimov, landing a job at the pig farm meant a break from his father's way of life, which demanded long hours. The two worked 12-hour shifts at an aviation plant, where Mr. Gerasimov started as a teen to help support his parents, whose two-room apartment hosts six family members. Now 24, he works a nine-hour shift at the farm and sells furniture on his days off.

That isn't unusual in this depressed area. Oxana Domakhina, a policewoman, also moonlights as a security guard at the town supermarket. "In the old days, you could buy a dozen eggs for 10 kopecks," she says. Now, the price is 36 rubles [$1.47] – 360 times higher. "Our life hasn't changed for the better."

Many here still struggle to eke out a living, though most homes now have a car in the driveway, a washing machine, and a VCR – all new in the past decade. Subsidies help with child care and utilities. One farm employee uses half her salary to pay for gas and electricity. Others don't pay anything – because they haul water from a well and chop their own wood for fuel.

Ms. Kuskova, the team manager, is one of them. In addition, she raises much of her own food since there's no store in her village. From April to September, she comes home from a nine-hour day and spends two to three hours coaxing onions, beets, and tomatoes from the ground – and flowers: "for ourselves, to be beautiful."