Arab TV feels the pinch of new broadcast limits

| Cairo

Spread across the top of this city's crooked skyline like a field of mushrooms, satellite dishes absorb signals beamed from across the Arab world to send images of pop stars and politicians to the throngs of families living below.

Throughout the Middle East, where governments have long had a powerful grip on the media, satellite broadcasting serves as an important source of information – and entertainment – that has been beyond the traditional reach of the state censors.

But now, according to rights groups and media observers, Arab governments are slowly moving to extend their control of the media to satellite broadcasters, as well.

In February, the Arab League adopted the Satellite Broadcast Charter, a new package of tight guidelines for broadcasters, at the instigation of Egypt and Saudi Arabia, which own two of the region's main satellites, Nilesat and Arabsat.

The document urges TV stations to "uphold the supreme interests of the Arab countries" and warns them "not to insult their leaders or national and religious symbols" or "insult social peace and national unity."

Weeks after adopting the charter, Egypt's Nilesat dropped Al Hiwar, a London-based network seen as sympathetic to the Muslim Brotherhood, the country's main opposition group. Following that, Egyptian police confiscated the transmission equipment of the Cairo News Company (CNC), a syndicate that news agencies such as Al Jazeera and the Associated Press rely on to broadcast their footage live from Egypt.

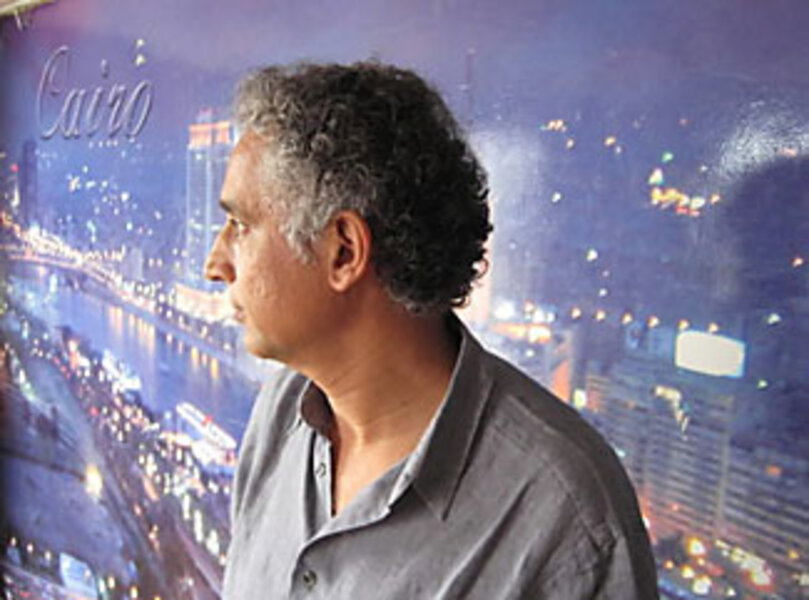

Nader Gohar, CNC director, says the government raided CNC in April because it blames it for images broadcast by Al Jazeera of protestors destroying portraits of President Hosni Mubarak during two days of food riots.

Although Mr. Gohar says that his company did not broadcast the images, and that Al Jazeera correspondents bypassed him and sent their footage directly to their Qatar headquarters from their satellite phones, he says a service provider such as CNC is an easier target than a major network.

"The government doesn't like what Al Jazeera says in their broadcasts, but at the same time it won't shut down their office," he says. "So they bother people like me because I give Jazeera the technical facilities they need to broadcast. It is an indirect way of limiting Al Jazeera's work."

Both the new charter and the seizure of transmission equipment from the CNC are part of the same repressive trend, says Lawrence Pintak, director of the Adham Center for Electronic Journalism at the American University in Cairo.

"It is all a symptom of the same reality, that this government and others in the region refuse to back away from the big brother mentality when it comes to the media," he says.

Egypt's media is freer than most in the Arab world. A number of independent newspapers and television channels have flourished here over the past several years, many of which were at their peak during a brief period of political openness that accompanied the 2005 presidential election.

President Mubarak handily won reelection in 2005, and his main challenger has languished in a prison cell ever since. As 2005 recedes further in to the past, the government has begun to move more aggressively against the press.

At the country's independent newspapers, editors, and journalists have been sentenced to jail for insulting the ruling party and speculating about the health of the country's leader, who turns 80 next month and has ruled Egypt for 27 years. Satellite broadcasters have started to feel the pinch, too.

Hussein Abdel Ghany, Cairo bureau chief for Al Jazeera, is concerned by the changing environment for satellite networks in the region, and in Egypt in particular. Al Jazeera was never consulted about the new guidelines issued in February, he says, but in particular he is "really worried about what is happening with our service provider," the CNC.

He calls the seizure of their equipment "a sneaky, indirect" way to attack freedom of the press.

"We rely on our cooperation with service providers, especially for covering live events," he says. "They are our only way to work here."

"If the government starts to close down service providers, or harass them to stop cooperating with independent media like Al Jazeera, the BBC, or the AP, then this is something that the international community and human rights groups that focus on freedom of speech should be paying attention to," he adds.

The state prosecutor has charged the CNC with violation of the 1960 Transmission Law, which gives the state-run Egyptian Radio and Television Union the sole right to transmit television signals out of the country. That law does not take into account the existence of technologies such as satellite broadcasting and the Internet.

The government has long promised to update the law, and will not renew the operating licenses of groups like the CNC until the law is changed.

Critics say the government has taken no action toward actually changing the law, and want to keep the media in a state of limbo.

"If you make a mistake the government will punish you for not having a license, but if you don't make any problems for them then you will be OK," says Gohar.

Critics say that those gray areas are the government's best weapon against the independent media.

Hussein Amin, the author of the Satellite Broadcast Charter, says that one of his goals for the document is to clarify those shades of gray. "Imagine you are walking in a dark room and someone turns on the lights," he says. "Censorship is that darkness and regulations are the lights."

He compares the guidelines to those of the Federal Communications Commission in the United States, and says it is meant to protect Arab youth from pornography, violence, and "hate campaigns" run by terrorist groups. "It was obvious that some channels were really designed just to implement hate campaigns against Christians in general and Americans in particular."

He points to Al Zawra, a channel run by Sunni militants in Iraq that was pulled from both Nilesat and Arabsat last year.

Mr. Amin, who is chairman of the journalism department at the American University in Cairo and a member of the policy committee of the ruling party, which advises Mubarak, says critics of the document do not under "the difference between freedom and responsible freedom."

"People need to remember that this is not the United States or Europe," he says. "This is still authoritarianism. The government can ban any network they want if it is giving them a hard time. They can ban it. They are in control."