'08 race has got religion. Is that good?

There was Mitt Romney's speech to try to dispel concerns about his Mormon faith. There was Barack Obama's denunciation of certain beliefs of his longtime pastor. Last week it was John McCain's turn to cut himself off from two controversial preachers whose endorsements he had once sought. And throughout the presidential primary season, there have been candidate forums on religious beliefs, plus eager courting of evangelical Christians, Catholics, and other faith groups.

Are religion and faith playing an appropriate role – or an inappropriate one – in the 2008 presidential campaign? So far, it's some of both, say those who've been monitoring the campaign.

There's no arguing that religious speech is more prominent than ever this election season. That's in part because Democratic candidates, traditionally reluctant to discuss religious views out of privacy concerns, have warmed to the topic in recognition that many voters want an understanding of how a president's religious convictions might influence him or her in office.

Whether this focus on candidates' religious views is helpful or detrimental depends, say political observers, on how the political parties, faith groups, and the news media handle faith issues in coming months.

Religious talk in ads and on the stump, "gotcha" questions during debates, and aggressive outreach to religious groups sometimes have crossed the line in ways that some observers say harm the country.

Inappropriate use of religion "can be dangerous and divisive for our pluralistic democracy ... and it can end up harming the integrity of religion," says Melissa Rogers, who teaches religion and public affairs at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, N.C. Religious ideas are much bigger than political parties or candidates, she says, but they lose their dimension when people in the pulpit suggest that voters of faith should support a particular candidate or that God looks with favor on one party over another.

According to polls, most Americans want a president with strong religious beliefs and they want to know how a candidate's faith shapes his or her values and policy proposals. The trouble comes, some say, when political leaders use religion as a weapon to inflict political harm.

"During the last couple of decades there's been a dramatic tilt toward a more partisan religious political culture," says David Domke, communications professor at the University of Washington in Seattle and coauthor of "The God Strategy."

Critics also cite news media that turn faith into mere entertainment or play it for controversy. Some questions asked during televised debates have been helpful, they say, but others have been inappropriate or irrelevant, bordering on religious vetting. The Interfaith Alliance (TIA), a religious liberty watchdog, became so concerned it released a video called "Top Ten Moments in the Race for Pastor-in-Chief." Among the questions it criticized: "What's the worst sin you've committed?" and "Do you believe every word of the Bible?"

"Why ask Senator Clinton about 'feeling the presence of the Holy Spirit'?" complained TIA president Welton Gaddy after the Compassion Forum aired on CNN in April. "Far more useful would be specific questions about how their faith would impact their policy positions."

Others, however, say voters have the right to ask questions that will tell them whether a candidate shares their values or worldview, religious or otherwise.

In defense of the event, the Rev. Jennifer Butler of Faith in Public Life, the group that sponsored the forum, said it was held "so people of diverse faiths could ask the candidates about moral issues that cut across ideological divides.... The voters care more about the common good than the culture wars."

Still, some questions have verged on the bizarre, such as asking former Governor Romney about Mormon undergarments. "The media thinks that since religion is a legitimate area of inquiry, somehow anything goes," Ms. Rogers says. "I hope we can work toward developing more good rules of thumb for handling this."

Foremost, though, how the parties and the candidates employ religion will determine whether the campaign is unusually rancorous or fosters discussion of values.

Some problems to watch for, says religion historian Martin Marty, include the flaunting of religious identity, the exploitation of religion, and attempts to squelch or denigrate other voices.

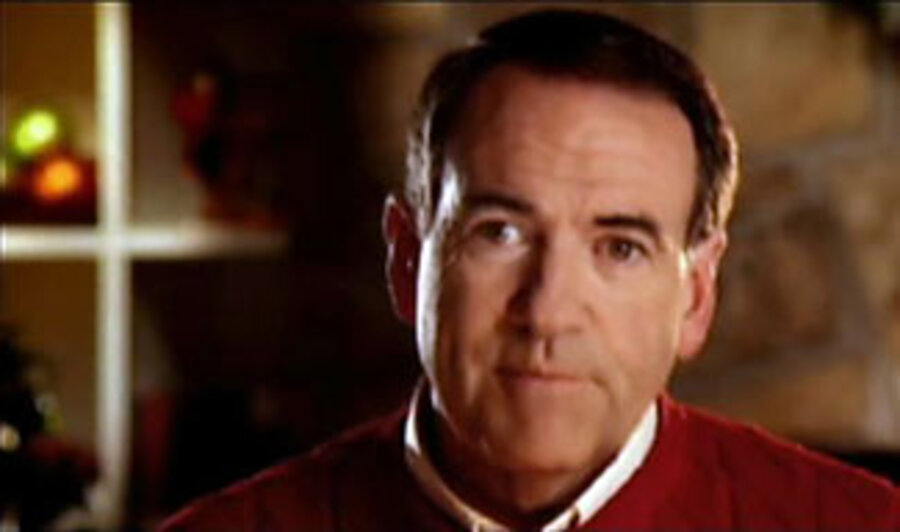

Former Gov. Mike Huckabee, an ordained Baptist pastor, was criticized during early primaries for emphasizing that he was "a Christian leader," for airing a Christmas ad in which bookshelf edges formed a white cross in the background, and for saying explicitly that his rise in the polls was due to divine influence.

A bit more subtly, Senator Obama in October told a congregation "I am confident we can create a Kingdom right here on earth" and issued brochures focused on his being a "Committed Christian."

Senator McCain – ordinarily reticent about faith – caused an outcry after asserting during an interview last September that America was founded as "a Christian nation" and saying he preferred a Christian president. Some saw his comments as more than just a mistake. "It was a subtle suggestion that Romney, a Mormon, is not Christian," says Dr. Domke. "And it helped him draw enough Christians to prevent all going off to Huckabee."

The campaign has also brought examples of denigrating others' convictions and misrepresenting their faith. In his speech on religion in December, Romney explicitly left out nonbelievers when he said that religion requires freedom, and "freedom requires religion." Such uses of faith, critics say, relegate millions of nonbelieving Americans to second-class citizens.

The most flagrant attack may be Web-centric efforts of unknown origin to paint Obama as a Muslim. Sen. Hillary Rodham Clinton in March seemed willing to benefit from that attempt when she said that it wasn't true, "as far as I know."

In response, Democrats who are not keen on the rising role of religion in the campaign seem willing to give Obama a pass on his "Committed Christian" brochures, seeing them as necessary to informing voters of the truth.

Many expect religion's high profile to continue through the general election. Some worry that tax-exempt political organizations, known as 527 groups, could act as a tinderbox, whether by resurrecting the controversial pastors or misrepresenting candidates' religious convictions.

"The ground here is volatile, depending on what candidates' supporters do," Domke says. "If the candidates can control these folks and squelch [negative] messages, we could have a pretty good discussion about faith and the presidency."