Mexican street art with an edge

| Oaxaca, Mexico

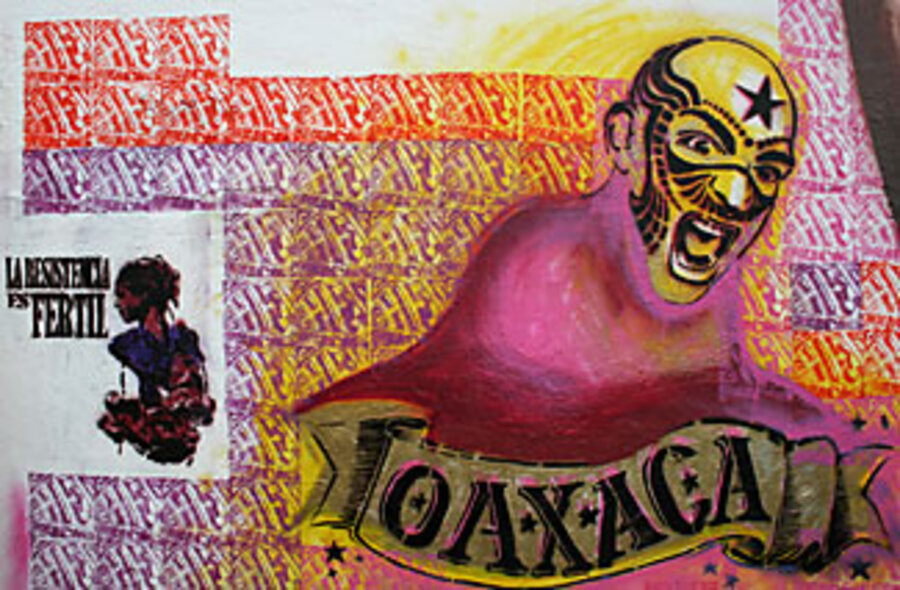

Scattered among Oaxaca City's brightly colored colonial facades, quaint coffee shops, and lavish hotels, there are signs of unrest. On a downtown street corner, a mural of a masked wrestler, mouth agape, is ready to leap from the wall. A few feet away, a spray-painted image depicts a woman with a child strapped to her back announcing a call to arms: "The resistance is fertile." Around the corner, a rainbow-colored ninja, sword drawn, bounds across a garage door.

In the two years since the Oaxaca City conflict, when protesters occupied the area after clashing with police, such politically charged artwork has spread across the city – as well as to the United States, where coffee shops and museums in New York City and Houston have exhibited the Oaxacan artists' work.

But in this state capital in southern Mexico, travelers don't need to visit a gallery; they can simply walk down the street.

To do so is to witness the past, present, and future of Mexican art: Many of these spray-painted and stenciled pieces borrow from the pop art of turn-of-the-century printmaker José Guadalupe Posada and the very public, very political, mural tradition of Diego Rivera. Others draw from the country's revolutionary iconography or the highly stylized flourishes of graffiti art.

"[The images] portray social realism," says Alan Schnitger, chief curator of "Defending Democracy," the exhibit at Houston's Station Museum featuring Oaxacan stencil artists. "Like popular grafica during the revolution in Mexico, they show the social issues – the farmers, the women, the teachers' union."

Scrawled across Oaxaca City's homes and storefronts – or for sale as woodblock prints in a city plaza – you'll probably see independence heroes, such as Benito Juárez or Emiliano Zapata. You may see a portrait of Frida Kahlo with a gun strapped to her back. Or a profile of an indigenous warrior with the word "Liberty" sprouting from his head. Or the bust of a sullen boy, looking downward, his eyes shaded in black.

These images didn't always adorn the city's architecture. It wasn't until the 2006 conflict that they began to appear, says Ivan Arenas, a member of the Assembly of Revolutionary Artists, a local artist collective.

Oaxaca's governor, Ulises Ruiz Ortiz, had called in police to disperse striking teachers, who gather in the state capital every May to strike for better pay and working conditions. The protest turned violent, and the teachers' strike expanded into a five-month demonstration: Protesters set up barricades, occupied radio stations, called for the governor's resignation and formed the Oaxaca People's Assembly. Several were killed, along with American journalist Brad Will.

As Oaxaca became embroiled in unrest, political art appeared around the city – in a basketball court, along its avenues, and in its main plaza, or zocalo.

"They became a community board, a medium of conversation.... The whole area around the zocalo was like one big mural project," Mr. Arenas says. "Tensions were high," he says. People "started putting up messages and images that went beyond the marches."

President Vicente Fox called in hundreds of federal police to squash the protest, but the political art continued. The clash had radicalized graffiti writers and fine artists who, beforehand, may have only been interested in tags or canvas. But this year, the artist assembly began holding technique-teaching workshops, Arenas said.

By the time Mr. Snitger of the Station Museum, and James Harithas, the museum's director, traveled to Oaxaca earlier this year, the assembly's work was well established.

"We went down and we knew something about it – we went down with the idea of wanting to showcase the democracy movement," Mr. Harithas says. "But in terms of quality, we didn't know what to expect."

So they met with assembly members and saw their printing press, wheat-paste posters, and woodblock prints. They were impressed.

"We didn't expect the passion these guys had. We didn't expect the fact that they would be working at such a high level," Harithas says. "We were pleasantly surprised. Their work is very strong."

The assembly isn't the only group working in Oaxaca City, however. Arenas says he knows of four other groups that paint the city's walls. Some explore human rights and political themes, such as the disappeared or the recent proposal to privatize Mexico's national oil company, while others are less weighty.

Perhaps one of the most common themes along Oaxaca's streets, however, is that of the fighter – that is, the wrestler, the ninja, or the indigenous warrior.

"The fighter becomes the symbol," Arenas says. "They're fighting for something. The theme of the 'lucha,' or the struggle, becomes much more broad."