A Westerner grows up in China

Loading...

China has been transformed beyond recognition since the ruling Communist party decided 30 years ago this week to abandon Maoism, build a market economy, and dismantle the "bamboo curtain" that had isolated the country from most of the world. This series explores what "reform and opening" has meant to the everyday lives of six individuals.

BEIJING – The fact that Ke Lu spent several years during the Cultural Revolution at a Beijing metalworking factory, making joints for the four-inch pipe that ran the length of the Ho Chi Minh trail, might not on the face of it sound very unusual.

Ke Lu, however, was not just another anonymous face on an industrial production line. He was also Carl Crook, an Anglo-Canadian teenager, and the middle aged businessman he has become – still living in China – looks back on his tumultuous youth now with an air of vague bemusement.

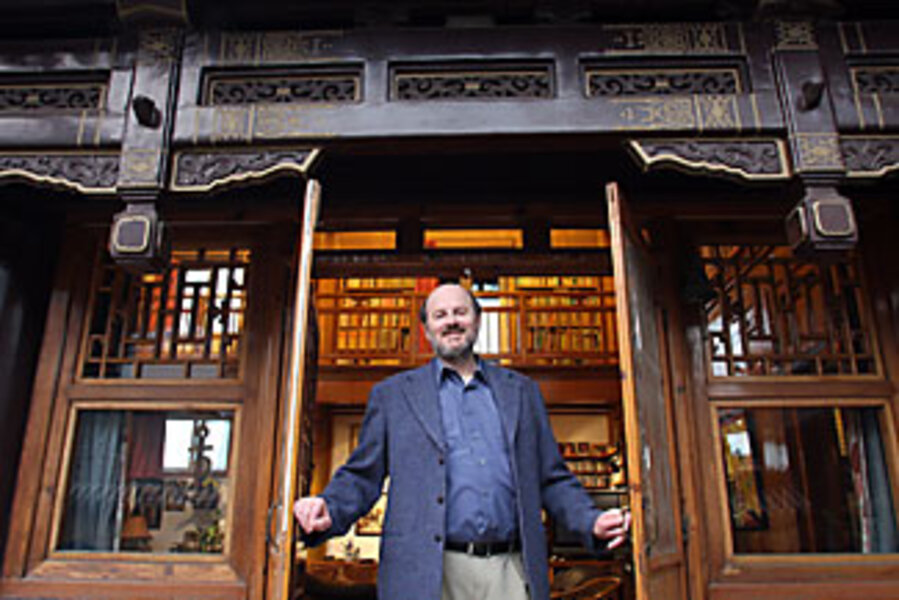

"I would never have expected then that I would end up doing business in China, especially not importing wine," says Mr. Crook, ensconced comfortably in a leather armchair in the spacious living room of his Chinese-style home. "It would have seemed so outlandish."

Crook would never have lived in China if it hadn't been for Mao. He was born in Beijing in 1949, the year of the revolution, because his parents believed in the "New China" and had come to work here. But he would not still be living here today, he adds, if the country had not wrenched itself out of Mao's shadow during 30 years of "reform and opening."

"It's not because of [having] material things, but there was a lot of uncalled for vigilance back then, a lot of busybodies" keeping neighbors up to the revolutionary mark, he recalls.

Westerners were virtually unknown in China when Crook was growing up, which earned him and his family special attention. Sometimes it was harmless: Astonished gawkers would block the streets when he and his family were allowed to travel into the countryside. Sometimes it was tragic: Crook's parents were both jailed as spies during the Cultural Revolution, which is when he was assigned to the pipe factory.

No matter that Crook had attended Chinese school, spoke Mandarin like a native (he prides himself today on speaking better Chinese than his local office staff), and had adopted a Chinese name. His physiognomy set him apart and kept him within bounds.

"We were hemmed into a radius of 15 kilometers," he recalls. "There were big blue-and-white enamel signs on all the roads out of Beijing in Chinese, Russian, and English: "Foreigners without permission are not to exceed this point."

Those warnings are long gone. And while Crook's life has been transformed by both aspects of "reform and opening" it is the "opening" that he values more.

"Growing up here I was always conscious that I was a liability to my (Chinese) friends," he recalls. "Just to be seen with me could be a problem for them and I was always very grateful to the ones who didn't mind."

Today, he says, one of the changes about China that pleases him most is the way he "can talk to people without their feeling any great apprehension about associating with foreigners. There's no fear about that now."

With more than 400,000 foreigners living in China today, mostly drawn by business opportunities, "long noses" are no longer a rarity except in small towns, and that traditional term for foreigners has almost completely dropped out of use.

"The world is part of their lives," Crook says of his former classmates, most of whom have prospered in later life. "Half their kids are living abroad and it doesn't shock them. The only travel they ever did then was when they were sent to the countryside."

It is that new openness of spirit "a readiness to try new things" in Crook's words, that has fueled the business that he founded and now runs – a wine importing company. And the appetite for foreign luxuries is booming among China's growing ranks of wealthy consumers.

In the old days, Crook remembers "foreigners were kept apart not just so that they would not fraternize too much with Chinese, but so that they would spend more" in special stores and restaurants. "In the restaurant business now it's the Chinese who are the big spenders. The tables have been completely turned at the high-end places."

At the same time, the Chinese government has grown less afraid of foreign influences. Crook remembers bringing his father a new shortwave radio every time he returned from a trip abroad, so that the old Englishman might tune in to his beloved BBC, which in official parlance constituted the crime of "furtively listening to an enemy station."

Nowadays, like anyone else, Crook listens to the BBC on the Internet. And he doesn't have to fear neighborhood snoops.