How team of rivals could still save Zimbabwe

Loading...

| JOHANNESBURG, South africa; AND HARARE, zimbabwe

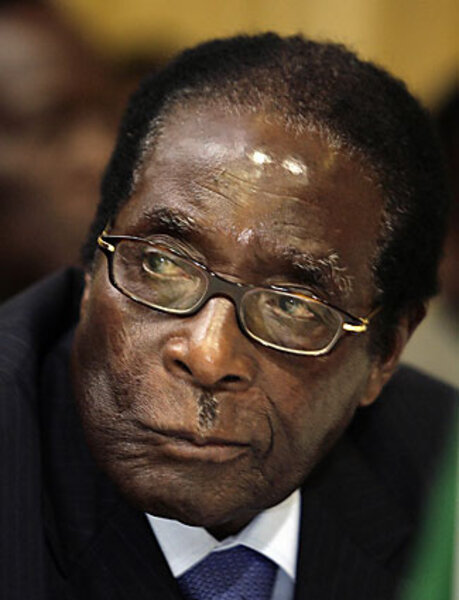

If old habits are hard to break, how will Zimbabwe's two warring parties – one led by opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai, the other by longtime President Robert Mugabe – work together in a coalition government, as Mr. Tsvangirai agreed to do last Friday?

The good news is that after nearly a year of political stalemate and economic collapse, these enemies may have no choice. Mr. Mugabe's long rule has left the country bankrupt, hungry, disease-ridden, and in desperate need of foreign aid. Tsvangirai may not have troops, but he has things Mugabe desperately needs: access to foreign donors and expertise that can make Zimbabwe function again.

It may not be a match made in heaven, but Tsvangirai – the presumed junior partner in a coalition government – can still make a difference in setting priorities – ending the cholera epidemic, fixing basic systems of water and sanitation, and rebuilding the economy – that would give him political leverage in the long term.

"They will work together because of circumstance and not because they want to," says Simon Badza, a University of Zimbabwe political science lecturer. "There is too much pressure on the two parties, locally from the starving masses and fromthe region who want a resolution of the Zimbabwean crisis."

Where does a new government begin to rebuild a country as neglected and self-destroyed as Zimbabwe? Tsvangirai's best chance at political survival may be in making a few decisions that immediately affect the lives of Zimbabweans. Once regional leaders, especially South African President Kgalema Motlanthe, realize Tsvangirai can deliver on his promises, they might begin to take him at least as seriously as they do Zimbabwe's combative and elderly head of state, Mugabe.

"The leverage that Tsvangirai has is his access to international resources," says Adam Habib, deputy vice chancellor of the University of Johannesburg. While few foreign donors would give aid to a regime as repressive as Mugabe's, many are lining up to give funds to a government led by Tsvangirai, with a parliament controlled by his party, the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC).

"If he uses that access to capital in a way that begins to address the national crises, you start to shift the ground underneath Mugabe. Regional leaders look at Tsvangirai again and say, 'This guy is working.' And you begin to isolate Mugabe from his base," Mr. Habib continues.

One priority that could be dealt with quickly is the spreading epidemic of cholera. Years of neglect, and a cash crunch that made water purification chemicals too expensive, have made Zimbabwe's public water supply too dangerous to drink. Tsvangirai could hire engineers from South Africa, Europe, and beyond to sort out the problem in very little time.

Showing competence will reassure foreign donors that Zimbabwe is safe for aid and investment again. Tsvangirai's demonstrating access to foreign sources of money could attract members of Zimbabwe's political elite, who long regarded Mugabe's ZANU-PF as the only show in town.

Increased foreign aid may help to bring many of the public services such as schools and hospitals back into operation. All this aid money will be conditional, of course, on promises Mugabe's regime will allow free political expression, or at least avoid the brazen repression of political dissent. If Mugabe needs capital more than a bashing of heads, then Zimbabwe's political climate is likely to open up.

The country's schools and health centers have been shut for the greater part of last year as teachers and health personnel respectively went on strike demanding better pay and working conditions. Towns and cities have no running water. Nearly a year's worth of refuse clutters potholed roads, neglected by unpaid civil servants.

Ozias Tungwarara, a Johannesburg-based expert for the Open Society Institute, says the key factor for Zimbabwe's recovery is free expression. "Tsvangirai has to ensure that there is popular participation in political and economic decisionmaking," he says. "The system where government is unaccountable to anyone is what got us to where we are."

Constitutional law expert Lovemore Madhuku calls MDC's decision to join a coalition government with Mugabe "catastrophic." Repressive and corrupt habits by Mugabe's government will not die right away, and MDC may soon find its credibility tarnished, he says. "A few months down the line, MDC will see that they have been taken for a ride."

He says by joining the power-sharing government, Tsvangirai has legitimized Mugabe, who's accused of gross human rights violations and ruining the country's economy during his 28-year tenure.

The two leaders' warring personalities will bring the country back to stalemate, Mr. Madhuku adds. The power-sharing government will be one "with two different people who can't work together to produce a position outcome."

Yet, Mugabe may need Tsvangirai to shore up his sagging legitimacy. The Mugabe who obliterated a rival liberation movement, ZAPU, before swallowing it into ZANU-PF in a 1987 Unity accord, is a much weaker man today.

Regarded as a pariah by much of Europe, and kept at arm's length by a growing number of African leaders, Mugabe now wants international recognition and access to funds from institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, says one Harare-based commentator.

"He will quickly see to normalize relations with the West so that they will be morally compelled to support the inclusive government," the commentator says, speaking on condition of anonymity. "This is a critical moment for Mugabe to save his disintegrating party. ZANU-PF needs this unity more than the MDC."

• A correspondent who could not be named for security reasons contributed to this story from Harare, Zimbabwe.