California's drought raises rural-urban tensions over water

| Los Angeles

California's third year of drought is stirring up long-standing – and usually low-simmering – tensions between farmers in northern and central California and urban consumers in the state's dry Southland.

The competition for scarce water was evident this week, as up to 19 million southern Californians learned they would face mandatory water restrictions for the first time in 18 years and as tens of thousands of farm workers marched through the Central Valley to protest federal and state cuts in irrigation water for the current growing season.

Though Los Angeles is recommending a cut in water use of 15 percent – and surcharges for those who miss the mark – the agricultural set is not placated. The cutbacks for consumers are not nearly equal to what's happening in farm fields, where growers don't expect to get any federal water deliveries at all and have had to lay off thousands of workers.

It's "too little, too late," says Central Valley farmer Stephen Patricio of the urban water-conservation measures. Los Angeles should cut water use by at least 30 percent, he says.

The Metropolitan Water District (MWD) of Southern California on Tuesday announced cutbacks to local water agencies, citing the drought and the tighter environmental restrictions in northern California's Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, which supplies much of the water to the south. Los Angeles, for instance, gets half its water from the MWD.

"Up to 19 million southern Californians this summer will feel the impact of a new water reality that has been in the making for years, if not decades," said MWD board chairman Timothy Brick in a statement.

In the Central Valley, meanwhile, tens of thousands of farmers, farm workers, and local officials protested federal and state water cuts during a series of marches this march.

Between 70,000 and 80,000 farm workers are out of work this year as a result of water shortages, according to a study from the University of California, Davis. California ordinarily supplies America with half of its fruits and vegetables.

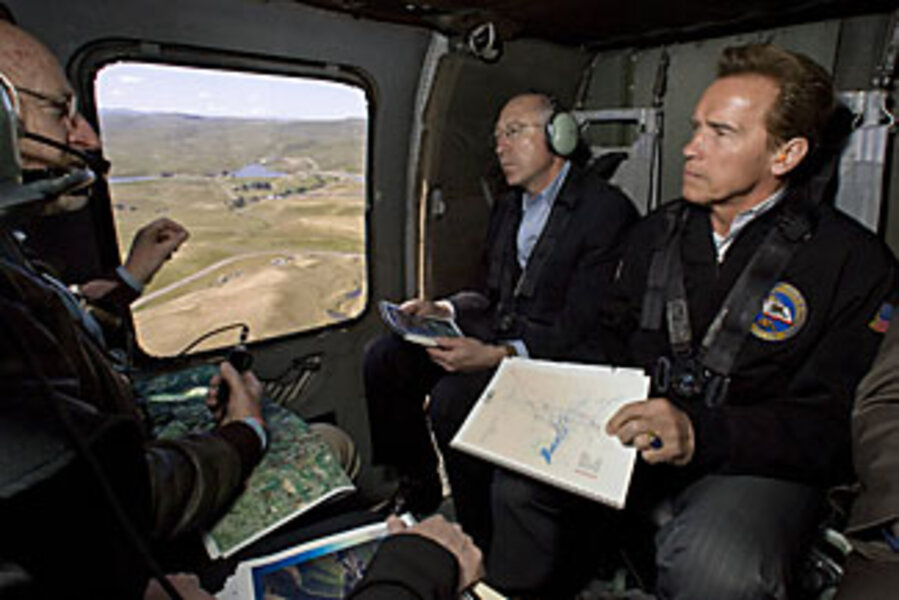

Earlier this week, Interior Secretary Ken Salazar pledged $260 million in federal stimulus money for drought relief and water restoration projects in the state. The funds include $109.8 million for a screened pumping plant at the Red Bluff Diversion Dam to protect fish populations, $20 million for Contra Costa Canal, and $40 million for immediate emergency drought relief in the West, with a focus on California.

Angry Central Valley farmers were not impressed. It's a "slap in the face," said Mr. Patricio, describing the stimulus pledge as "a touchy-feely, warm-and-fuzzy, feel good, pork project without any true benefit."

Patricio, who is also chairman of the board of directors for the Western Growers Association, says he has laid off hundreds of workers on his 2,000-acre cantaloupe farm near Firebaugh in the past few years, and watched dozens of his neighboring farmer friends go belly up.

"We've spent hundreds of millions studying the problem when we could have spent that same money on fixing it," he says.

Farmers in the Central Valley are asking for a new canal to get water from the Sacramento River, as well as a relaxation of environmental restrictions resulting from a 2007 court ruling limiting the amount of water pumped south from the delta – a giant sponge that absorbs runoff from the wetter north.

The ruling was in response to a suit by environmental groups that held that the water pumping through the delta endangered several species of fish, including smelt, green sturgeon, and winter and spring salmon.

The MWD also raised its rates citing the higher costs caused by these environmental restrictions. It has approved an 8.8 percent increase in the district's base wholesale water rate plus a $69-per-acre-foot Delta surcharge.

The surcharge reflects the loss of state water supplies due to the environmental collapse of the Delta, said MWD general manager Jeffrey Kightlinger in a press statement. The collapse has "required us to purchase expensive replacement supplies, accelerate funding of alternative water supply programs and finance Delta sustainability projects, including the protection of endangered species," he said.

Environmental regulations in the delta will reduce water deliveries by as much as 40 percent, he added.

"We're beginning to get to the real cost of water," says Colin Sabol, vice president of marketing for ITT Corporation, the world's largest provider of pumps and water equipment. He notes that US consumers pay on average only one-third of what Germany pays for its water.

Germany "charges a price that allows them to reinvest in their infrastructure," Mr. Sabol says.

Gloria Goodale contributed to this report.