Where did all the bailout money go?

It's enough to boggle the mind. If all goes well, it'll be enough to help the economy recover.

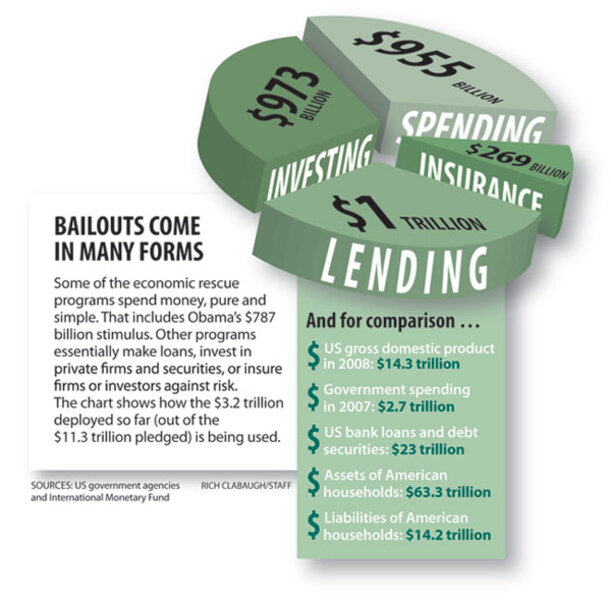

The US government has deployed more than $3 trillion in an all-out effort to resolve a financial crisis and end a recession. It is acting as lender of last resort, investor of last resort, and consumer of last resort.

After more than a year of extraordinary federal interventions in markets and private companies, much still hangs in the balance.

At best, the federal efforts could stabilize the banking system, ease a record foreclosure wave, and kick-start an economic recovery. Then the Federal Reserve and Treasury would withdraw their stimulus before it sparks inflation or a run on the dollar by foreign investors.

At worst, the rescue could fizzle. While putting out a fire for a season, it could leave key banks still weak and the economy stalled, all while piling up a dangerous level of federal debt that limits options for the future.

Or the result could be something between those extremes. However it all turns out, the government strategy in some ways echoes the very banking behaviors that helped to launch the crisis: expanding its own leverage (debt) to extend high-risk credit to others.

Here's a guide to the rescue programs, in questions and answers.

What's the recovery effort costing?

A lot, but economists can only guess what the final tab will be. The federal government has allocated more than $11 trillion to fight the recession and financial crisis – an amount that approaches one year's output of goods and services in America. But much of that money is the potential size of rescue programs, not their actual scale (now about $3 trillion).

The amount of money used, moreover, may not be the true cost. Some very large programs may never cost taxpayers a dime. For example, the Federal Reserve stands ready to make as much as $1.8 trillion worth of 90-day loans to corporations – by buying their so-called commercial paper. It's the largest single rescue program, launched when private-sector funding markets froze in a panic last fall. But the money is going out only to firms with high credit ratings and it gets repaid within three months.

Many US interventions amount to lending, investing, or insuring, not direct spending. Hence, the cost to taxpayers will depend on how the economy fares, which will affect how many loans or investments fail to pay off. At a minimum, though, nearly $1 trillion already has been committed in direct spending – the Bush and Obama stimulus plans.

Where's the money coming from?

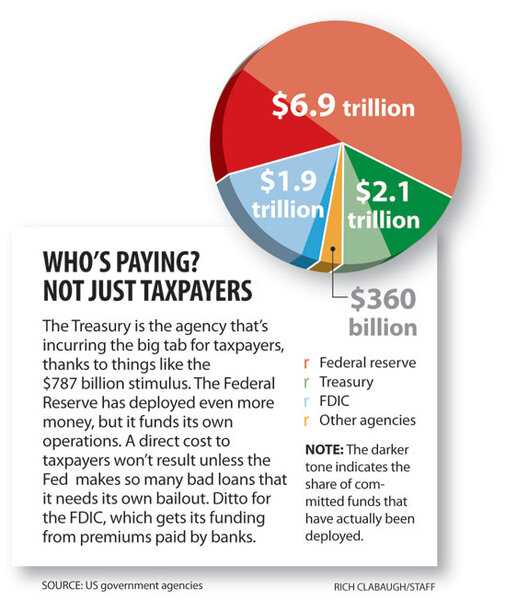

It comes from two main sources. The first is the Federal Reserve, which can expand its balance sheet (that means "spend" to you and me) at will. The goal is what Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke calls "credit easing" – to ensure a normal flow of credit at a time when many institutions and investors are reluctant to lend. But when the Fed expands its asset base by making loans, a side effect is to expand the money supply in the economy. That can lead to inflation, but so far it's just offset part of the contraction in private-sector financial activity.

The second is taxpayers. It's not that income-tax rates have gone up lately, but Americans are on the hook in the long run. The spending adds to US debt. This also means, by the way, that the rescue's ultimate cost depends on future changes in the government's borrowing costs.

For now, the Treasury can issue bonds at very low interest. But those debts will probably roll over into new T-bonds a few years from now, quite possibly at higher interest rates.

Why is this big bailout happening?

Without intervention, the recession would be much worse, say policymakers. The causes are many, but the deflation of an overheated housing market triggered a chain of problems. Investors, who had financed a great deal of lending by buying credit products, retrenched. The health of banks deteriorated. The stock market fell. All this rippled out to affect consumer confidence and business prospects.

Now the goal is to keep job losses to a minimum and to prevent a lack of credit from choking the hoped-for recovery.

Is the rescue plan working?

One good sign is that the financial system hasn't experienced a meltdown. That was a real fear in September, when the US witnessed the financial equivalent of the Three Mile Island nuclear alert.

After that panic, the bailouts ramped up in earnest. The Bush administration and Congress fashioned an emergency response – the $700 billion TARP, or Troubled Asset Relief Program.

Key credit indicators have improved since then. Mortgage rates are down, for example.

Federal money is helping banks lend more than they otherwise would, and the banks are paying dividends back to the Treasury, says Brian Bethune, an economist at IHS Global Insight in Lexington, Mass.

"That strategy is working," he says, "despite all of the weeping and gnashing of teeth over that TARP."

Many economists are hopeful that the worst of the crisis is in the rearview mirror. But the economy and the financial sector remain fragile.

Will more money be needed? Where?

More money will probably end up going to some folks who are already big recipients. The Treasury wants to make sure big banks have adequate capital to make loans.

If the recession deepens, the political pressures could tug two ways. More firms could be in trouble and claim that they are "systemically significant," in the Treasury's phrase. But the Treasury might run into limits on the number of bailouts that Congress is able or willing to fund.

Is the U.S. government going broke?

Not yet. The US still enjoys a AAA credit rating, but some economists worry that may not last. The big danger, they say, is that bailout costs are adding to the national debt just before a big rise in entitlement spending for new baby-boomer retirees. The Obama administration knows that if a fiscal course correction doesn't emerge in the next few years, foreign lenders could worry about inflation risks. That could hurt the dollar and push up Treasury borrowing costs.

What are the government's alternatives?

The most widely advocated one is for regulators to take over insolvent banks and fix them in the cheapest way possible. In many cases, shareholders would be wiped out, bondholders would be asked to swap their debt for equity, and the firm could return quickly to private ownership.

If those changes wouldn't be enough to make a bank solvent, the government might strip out bad assets and manage them separately, while creating a "clean bank" to be sold to private owners.

Both conservative and liberal critics of the Obama plan advocate such an approach or alternative plans.

"Make no mistake, we are selling off our future and the future of our children to prevent the bondholders of US financial corporations from taking losses," mutual-fund manager and economist John Hussman wrote last month. "We are using public funds to protect the bondholders of some of the most mismanaged companies in the history of capitalism, instead of allowing them to take losses that should have been their own."

How can such a mess be avoided in the future?

Policymakers are busy trying to craft a new regulatory structure. One issue under review is how to tie bankers' pay to risk management, not just profitability.

Another is whether to prevent financial firms from getting so large that regulators consider them "too big to fail."

Sheila Bair, who heads the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., recently advocated "incentives to reduce the size of systemically important firms."

Some say the largest firms should pay new insurance fees to cover the high bailout costs they can impose in a crisis.