How an amateur beat the pros in spotting Jupiter collision

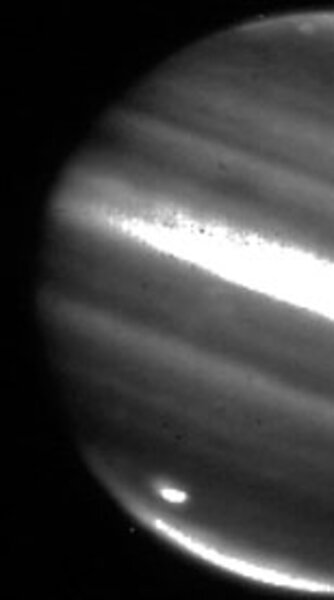

When an object plunged into Jupiter's cloud tops over the weekend, it left a darkened splotch the size of the Pacific Ocean for all to see.

But no one did at first, except Australian amateur astronomer Anthony Wesley. So, where were all those hot-shot professional astronomers and their multimillion-dollar telescopes?

Therein lies a tale of the synergy between professional astronomers and their unpaid counterparts, from engineers and book authors to Caroline Moore, who last November, at the astronomically early age of 14, became possibly the youngest person to discover a supernova.

Amateurs have historically made many contributions to astronomy, aided by serendipity, sheer numbers, devotion to a planet or star – and the luxury of not having to share their telescope with hundreds of other scientists.

The kind of data amateur astronomers can provide these days, particularly imaging data, can be "very impressive," says Brian Day, who heads up NASA's outreach effort to the amateur astronomy community at the Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif.

They shine especially on long-term projects, notes Adam Block, a noted astro-photographer who coordinates public programs at the SkyCenter, a public-viewing observatory the University of Arizona in Tucson runs on nearby Mt. Lemmon.

Amateurs track near-Earth asteroids and make repeat observations that help refine their orbits. They've joined the hunt for planets orbiting nearby stars. And they have helped astronomers follow long-term ups and downs in the light emitted by variable stars.

Invited to help by NASA

The latest high-profile opportunity for amateurs is an official one: NASA's LCROSS mission, a companion to the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter currently swinging around the moon. LCROSS is destined to slam into a lunar crater near the moon's south pole in October, kicking up a plume of material that may contain water ice.

The space agency already has enlisted amateurs to submit images of the plume to augment data from professional observatories on the ground and in space.

The amateurs' contribution "could be pretty major," says Faith Vilas, director of the MMT Observatory atop Mt. Hopkins, south of Tucson. The observatory she leads – operated by the Smithsonian Institution and the University of Arizona – boasts a telescope with a light-gathering mirror array spanning 6.5 meters (21.3 feet), and will be taking part in the international effort to observe the impact.

With the right equipment in the right location, and clear skies, amateurs will be in a good position to image the plume once it rises above the moon's surface, she says. The shape and structure of the plume will hold clues about the composition of the material kicked up and the part of the crater the impactor struck.

In addition, NASA has enlisted amateurs to take pictures of the moon's south polar region. The idea is to gather an atlas of the area as it appears under a wide rage of light conditions and orbital positions.

Mr. Day says the atlas will help identify small-scale geological formations that large observatories can use as "guide stars" to ensure their spectrographs remain aimed at the right spot.

A discovery nearly missed

One reason amateurs can make contributions to science is that they far outnumber the ranks of professional astronomers, Mr. Block says. And for sustained observations, they can keep their telescopes trained on an object as long as necessary. Professional astronomers, on the other hand, have to wait in a long queue for expensive telescope time. And they have another line of toe- tapping colleagues behind them.

So, for an amateur in the right place at the right time with all his or her gear running, there are plenty of opportunities for exciting discovery. Just ask Mr. Wesley, the Jupiter-watcher who almost missed the observation of a lifetime.

Atmospheric conditions had gotten so bad that he was about to close down for the weekend. He changed his mind and opted to take a half-hour break instead, but left his telescope's imaging apparatus running. When he came back, he writes in his observing report posted on the Web, he noticed a dark spot rotating into view in Jupiter's south polar region.

"It took another 15 minutes to really believe that I was seeing something new – I'd imaged that exact region only 2 days earlier and checking back to that image showed no sign of any anomalous black spot."

It was, he writes, "a very near thing."