Honduran crisis deepens as mediation stalls

Loading...

| Mexico City

The political crisis in Honduras deepened Wednesday, as the country's deposed president and its interim leader resisted a final proposal floated by Costa Rican president Oscar Arias.

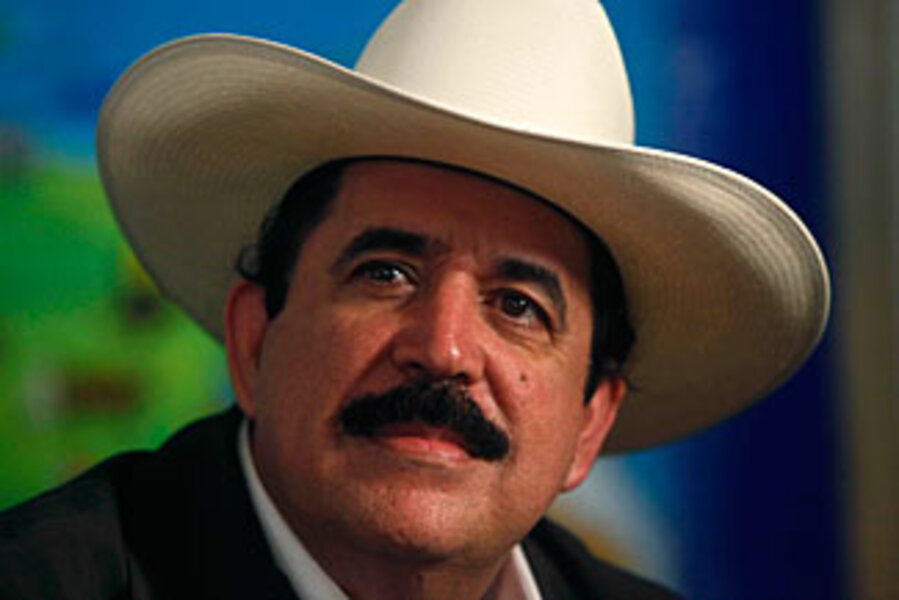

Mr. Arias said this would be his last attempt to forge a resolution, after Honduran President Manuel Zelaya was arrested by the military and deposed on June 28. An interim government, led by Roberto Micheletti, was sworn in hours later.

Mr. Micheletti's delegation has refused to budge from its opposition to any proposal that requires the return of Zelaya to carry out his term, which ends in January.

Zelaya is vowing he will return home by Friday, crossing the border from Nicaragua. On Wednesday, he declared the talks over.

"The coup leaders are totally refusing my reinstatement," Zelaya said at a press conference in Nicaragua. "By refusing to sign, [the talks] have failed."

Arias had pushed for the return of Zelaya by Friday in an 11-point plan that included early presidential elections and amnesty for political crimes.

The Nobel Peace Prize winner put pressure on both sides Wednesday. "The clock is ticking fast, and it's ticking against the Honduran people," he said. "I warn you that this plan is not perfect. Nothing in democracy is perfect."

Micheletti's delegation said it would return the proposal to Honduran institutions, but the Supreme Court earlier ruled that it would be illegal to reinstate Zelaya.

The interim government has become increasingly isolated as many nations, which have already recalled ambassadors and suspended aid, stepped up pressure this week: the European Union suspended $90 million in aid money and the US threatened tough new sanctions.

Daily protest marches

Both sides have been emboldened by their supporters. Supporters of Zelaya have marched daily but his foes have also taken to the streets. Tens of thousands, reportedly the biggest protest yet, marched against his return Wednesday.

Many of the nation's institutions were angered by his attempt to move forward with a nonbinding vote to consider altering the Constitution, a move that did not have congressional backing and was declared illegal by the Supreme Court.

Many feared his alliance with other leftists in the region, such as Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez, and worried that Zelaya was attempting to change the Constitution for the sole purpose of allowing him to run again for office, a charge he now denies.

Zelaya, on the other hand, has been backed by the international community. No foreign government has recognized the Honduran interim government, and the Organization of American States has repeatedly reiterated its stance that the only option is that Zelaya be returned to power.

Ultimately, Zelaya could gain support among Hondurans on the fence, says Daniel Hellinger, a Latin America expert at Webster University in Missouri, citing poll numbers by Cid-Gallup that show a near-even divide in public opinion, with a plurality of Hondurans disagreeing with the actions used to oust him from office.

"People recognized that the Congress and the [Supreme] Court had a case against him, but that it should have been pursued through normal, legal channels," Mr. Hellinger says. "Now, in a sense, he's been reinvented as an avenging angel against [the old ruling class]."

• Material from wire services was used in this report