CERN physicist accused of terror links. What access did he have?

When a physicist is suspected of working with terrorists, thoughts turn to radioactive "dirty bombs" or small nuclear devices – and global alarm bells go off. But when the suspect works at the world's largest particle accelerator, the world can breathe a half-sigh of relief.

Adlène Hicheur was reportedly a French-Algerian researcher who worked at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN). He was part of a large group running experiments at CERN's Large Hadron Collider (LHC). On Monday, he stood before a French judge in Paris, accused of collaborating with an Al Qaeda spinoff group in North Africa.

CERN is not the kind of laboratory that represents a terrorist's candy store, researchers say.

"There's nothing you can get at the LHC that can do any damage to anybody, except a hammer," quips Sheldon Stone, a physicist at Syracuse University in New York and member of the team running an experiment called "LHC Beauty." Mr. Hicheur worked for this experiment as a data analyst.

While the lab does use some radioactive material, the sources are common to hospitals and industry, according to a statement the lab issued after Hicheur was arrested. The lab is not involved with nuclear-energy research or nuclear weapons – activities that would be more likely to require, or produce as byproducts, highly radioactive materials.

According to officials at CERN, Hicheur hadn't been around the lab for months. The facility has been shut down since September 2008, after two magnets, which were designed to keep proton beams focused, overheated and melted.

Authorities reportedly picked up Hicheur in southeastern France on Oct. 8, along with his brother.

Hicheur is suspected of discussing with the Al Qaeda spinoff potential targets in Europe to attack. French officials reportedly have said that they had no evidence CERN was among the targets.

The collaboration that Hicheur participated in includes 650 scientists from 13 countries.

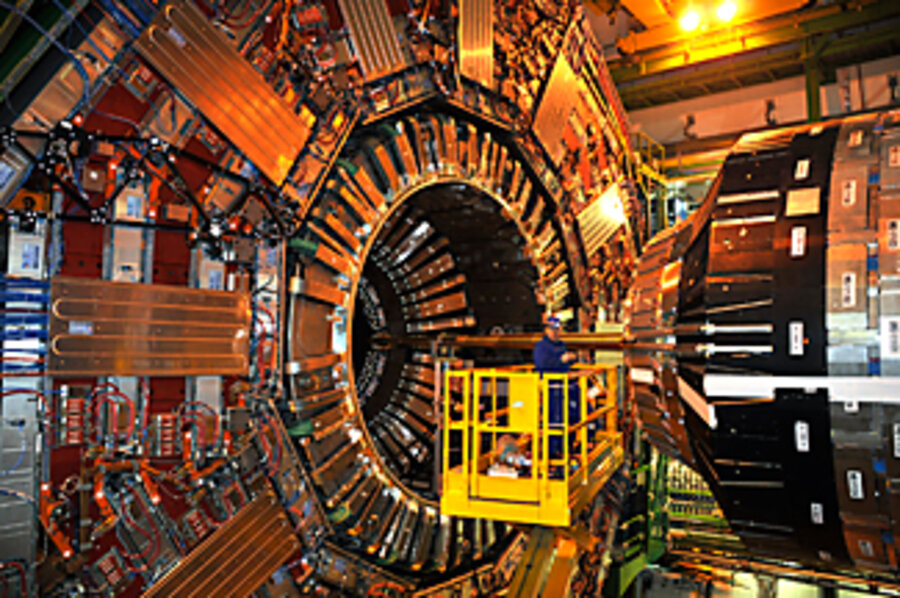

The LHC is designed to accelerate two beams of protons in opposite directions, then steer them into head-on collisions to mimic on a tiny scale conditions thought to exist in the briefest instant after the Big Bang. Physicists and cosmologists hold that this cosmic explosion formed the universe.

CERN officials plan to restart the particle accelerator in mid-November, now that engineers have solved the electrical problem that destroyed the two focusing magnets.

The restart is the first step in a gradual process to bring the accelerator up to full power later next year.

One goal for the accelerator – which has a circumference of 27 kilometers (16.8 miles) and straddles the French-Swiss border – is the detection of a particle called the Higgs boson. It's thought to be responsible for imparting mass to all the other subatomic particles.

In addition, the accelerator could uncover a range of other particles predicted to exist by theories trying to show how the four basic forces in nature are manifestations of what once was a single über force. The four basic forces are electromagnetism, the weak force (governing radioactive decay), the strong force (binding particles in an atom's nucleus), and gravity.

Scientists hope to create the particles directly by smashing protons together at sufficiently high energies. Other projects, such as Dr. Stone's LHC Beauty collaboration, aim to spot some of these particles indirectly as they decay into yet other types of particles.

-----

Click here for a briefing on the potential for an attack on Iran's nuclear facilities.

-----

Follow us on Twitter.