Northwest Airlines flight leads to probe of pilot professionalism

A commercial airline overshoots its destination by 150 miles? Have you ever heard of such a thing? Well, yes actually.

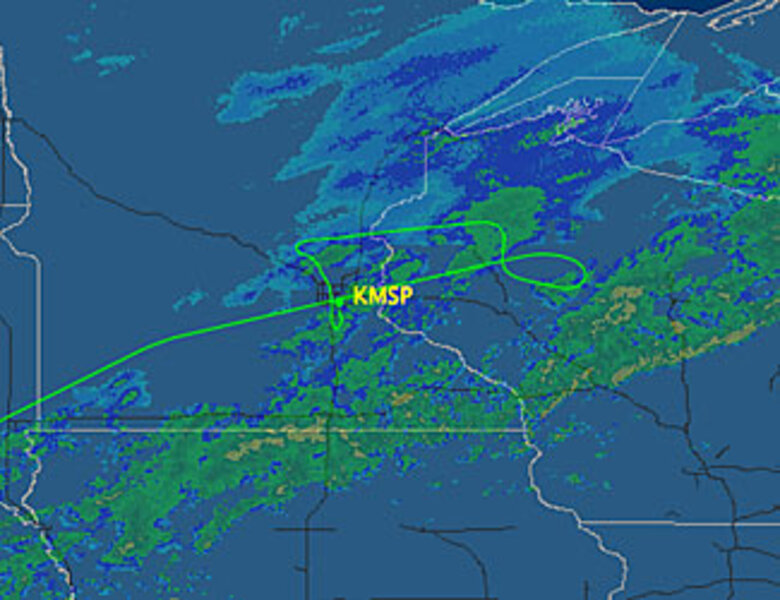

Investigators are probing the mystery of how Northwest Airlines Flight 188 overshot Minneapolis by so far on Wednesday night. But the incident joins other recent cases that have drawn attention to issues of flight-crew professionalism and alertness on US airlines.

The prominent examples include:

•Last year, two pilots for "go!", a subsidiary of Mesa Airlines, fell asleep during a mid-morning flight from Honolulu to Hilo, Hawaii. Traffic controllers finally got through to the pilots, and the plane landed safely.

•Continental Connection Flight 3407, a flight operated by Colgan Air, crashed near Buffalo in February, killing 49 passengers and one person on the ground. Crew fatigue, distracting banter in the cockpit, and lack of training or experience may have played roles in the crash, along with wintry weather.

•Pinnacle Airlines Flight 4712 skidded off a runway in Traverse City, Mich., in April 2007. The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) determined that the crew shouldn't have tried to land. The captain was making his fifth landing on a short airstrip that day, according to the Associated Press, and had been working for 14 hours in mostly bad weather.

And, according to AP, the NTSB has linked crew fatigue to at least 10 US airliner accidents (and 260 fatalities) since 1990.

For years, the Federal Aviation Administration has considered updating old rules on fatigue prevention, but efforts stalled amid differing views from constituencies such as pilots unions.

Since the Colgan Air crash, the FAA has tried to put the matter on a fast track, along with other safety issues such as a heightened focus on professionalism in the cockpit. But the agency's rulemaking efforts are still in process.

In the Colgan crash, and one in Lexington, Ky., crews violated "sterile cockpit" rules, requiring that officers not chit-chat during takeoffs or landings, according to recent congressional testimony by FAA administrator Randolph Babbitt.

Current rules on fatigue require that pilots not fly more than 8 hours in a day, or work more than 16 hours including time on the ground. But they don't take into account the varied experiences of pilots.

An eight hour shift on short routes might include eight takeoffs and landings, for example, a much more stressful day than piloting a cross-country flight. Similarly, some crews work late at night or have long commutes by air before going on duty.

New FAA rules, under review in draft form, are expected to address such issues. Fatigue issues have also surfaced as a safety concern in other transportation fields, including trucking and railroads.

The Northwest Airlines incident this week, which ended with a safe (but late) landing in Minneapolis, could bring other issues to the fore, depending on where the investigation leads.

Earlier this month, the House of Representatives passed an air safety bill backed by Rep. Jerry Costello (D) of Illinois. It includes provisions to establish pilot mentoring programs, boost training requirements for pilots, and create a pilot records database so airlines have access to a pilot's comprehensive track record.

Despite the signs that more progress is needed, the air travel industry has remained generally very safe. The fatality rate has been declining in each of the past three decades, according to the Air Transport Association.