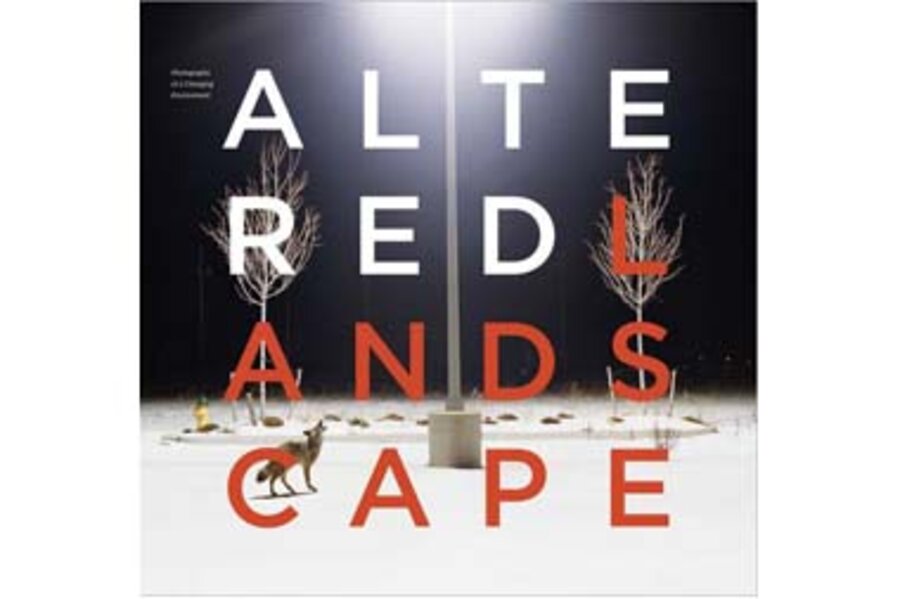

The Nevada Museum of Art is dedicated to changing our dated notion of landscape photography. The photos in The Altered Landscape (Rizzoli, 288 pp.), the companion book to the exhibit of the same name, are culled from more than 900 photographs the museum has amassed since the 1970s. Featuring 150 images by 100 photographers, the compendium dramatically illustrates the impact of human beings on the planet’s topography.

There are few pastoral scenes and romanticized visions of the natural world in this book. Instead we are confronted with the “marks” we have created upon the landscape for good or ill. As curator of exhibitions and collections Ann Wolf explains, “the images ... suggest that the earth’s surface offers an irrefutable record of some of civilization’s most impressive endeavors – as well as its worst failures.” These pictures don’t preach against what is inevitable or avoidable. Instead, there is beauty in damaged as well as pristine places. The photographers implore us to stop, look, and think about what this means for us as well as for the ground beneath our feet.

David Maisel’s “Terminal Mirage 18” underscores this plea. This exquisite abstract is taken from his series “Terminal Mirage,” photographed at the Great Salt Lake in Utah. The area is dense with naturally occurring minerals that create vivid colors. But the myriad mining operations surrounding the lake suggest the hues are derived from more sinister elements. We do not know what is toxic – naturally occurring or man-made. Yet the beauty of the photo draws us in, giving us time to ponder the source and ask questions.

Virginia Beahan and Laura McPhee, collaborating photographers, created a more literal political statement in “The Blue Lagoon, Iceland.” A child plays with a boat in calm water, across the shore from a steam-emitting geothermal plant. The pastel colors further exaggerate the utilitarian imposition upon the land. The human imprint here is a more imposing presence than the sleepy town surrounded by desert in Ansel Adams’s “Moonrise, Hernandez, Mexico.”

Traditionally, landscape image makers believed that seeing a beautiful site would inspire conservation. Since the 1970s, a small coterie of environmentalist photographers have made the natural world their subject matter in a manner more inquisitive and political. Based in an emerging philosophy that fuses personal vision with documentary discipline, these photos are more art than document, yet more narrative than invented. It is fitting that the Nevada Museum of Art would bring these imagemakers together in a signature collection celebrating their 80th anniversary. This book will expand the audience and, hopefully, the conversation.

Reviewed by Joanne Ciccarello, Monitor staff photo editor