From Africa to Alabama: Stories of survivors of the last slave ship

Loading...

The horrors of the trans-Atlantic slave trade are often expressed in numerical terms whose enormity can be difficult to grasp. Between the 16th and 19th centuries, 12.5 million people in Africa were forced onto slave ships bound for the Americas; 10.7 million survived the crossing and entered a life of bondage. As a result of the brutal conditions that captives were subjected to on the ships, 1.8 million died along the way.

The story of the Clotilda, the last slave ship to arrive on U.S. shores, gives human dimension to those staggering statistics. As British historian Hannah Durkin observes in her absorbing and affecting book “The Survivors of the Clotilda: The Lost Stories of the Last Captives of the American Slave Trade,” the circumstances of those on the ship were uniquely well documented. “Archival material relating to the Clotilda and its survivors collectively represents by far the most detailed record of a single slave ship voyage and its legacies,” she writes. “Moreover, it is the only Middle Passage story that can be told comprehensively from the perspective of those enslaved.”

The wealth of information stems from the voyage’s timing. The Clotilda docked in Mobile, Alabama, in July 1860, five decades after the abolition of the American slave trade. (Slavery itself was not abolished until 1865.) The illegal endeavor grew out of a $1,000 bet made by planter Timothy Meaher, who boasted that he could elude the ban and successfully import a ship of human cargo. He won the wager, and he was never punished for his crime.

But because the Civil War erupted months later, the Clotilda survivors – who were all abducted from the same town in present-day Nigeria by raiders from the kingdom of Dahomey in present-day Benin – were emancipated within five years. They attracted the attention of researchers and writers who were interested in interviewing formerly enslaved people who remembered their lives in Africa and could describe the miseries of the middle passage.

The ship itself has drawn attention. Its sunken remains, which were concealed by Meaher and his co-conspirators, were finally uncovered in 2018; Ben Raines, the journalist and charter boat captain who discovered the wreckage, published a gripping book, “The Last Slave Ship,” in 2022. That year also saw the release of “Descendant,” a feature-length documentary about the Clotilda. Both the book and the film address efforts by the progeny of the survivors to wrestle with their traumatic family histories.

For her part, Durkin remains focused on the Clotilda passengers themselves. She begins with the kidnapping and sale of 110 captives, primarily teenagers and children, to the ship’s captain, William Foster. (He chose young people who would presumably be able to labor and bear children for years to come.) After chronicling their perilous and frightening 45-day voyage, the author goes on to describe the sale of the 103 survivors of the journey to various enslavers in Alabama, their five years of bondage, and their hardscrabble lives following emancipation.

Some of the shipmates attempted to raise money to return to Africa after the war; when their efforts failed, they bought land from Meaher, their former enslaver. They created a community known as Africa Town (now called Africatown), which, in Durkin’s words, was “a highly ordered society that drew on the social structures and teachings they learned as children.”

One of Africa Town’s best-known residents was Cudjo Lewis, also known as Kossula, whose recollections formed the basis of Zora Neale Hurston’s nonfiction book “Barracoon.” When he died in 1935 at the age of 94, he was remembered as the last living person brought to America on a slave ship. But Durkin’s research reveals that a woman named Redoshi outlived Kossula by more than a year.

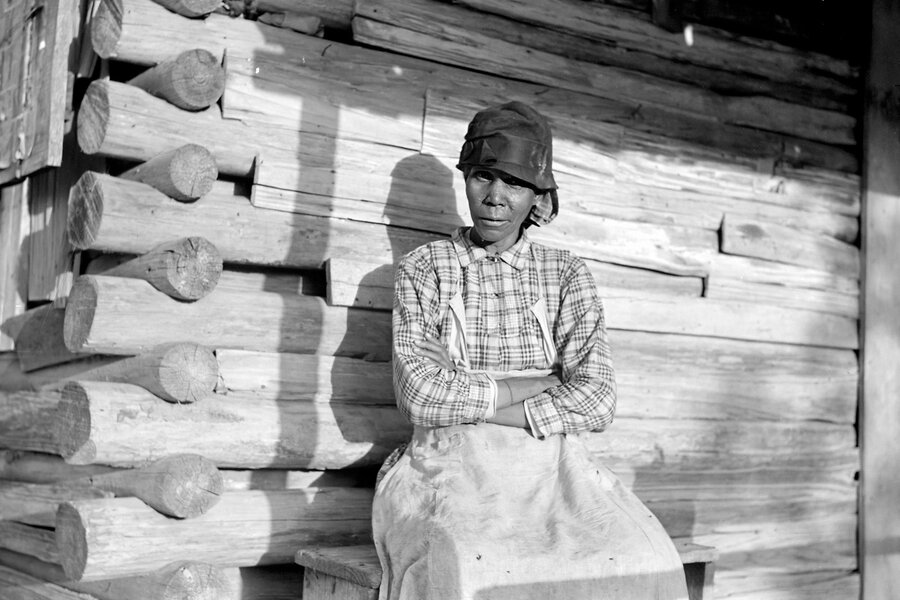

It’s a fitting discovery for a book that sheds new light on the experiences of female survivors of the slave trade. In interviews, Redoshi recalled the hard labor and frequent beatings during her years of enslavement. Like many of the other Clotilda survivors – and like African Americans in general in the post-Reconstruction South – she struggled in the face of economic exploitation, racial violence, and the loss of political rights. She lived on her enslaver’s property because she had nowhere else to go. “Redoshi was never able to escape her poverty and only nominally did she escape slavery,” Durkin writes.

The author captures the complexities of the survivors’ experiences. “Their lives document the manifold ways, big and small, that a group of enslaved children and young adults resisted their imprisonment, impoverishment and geographical isolation and asserted their West African identities in the United States both during and after slavery,” she notes. Still, even while stressing their extraordinary endurance, Durkin never loses sight of what was lost. Decades after emancipation, Clotilda survivor Osia Keeby was interviewed by Booker T. Washington, who asked the older man if he hoped to return to his homeland one day. Keeby replied, “I goes back to Africa every night, in my dreams.”