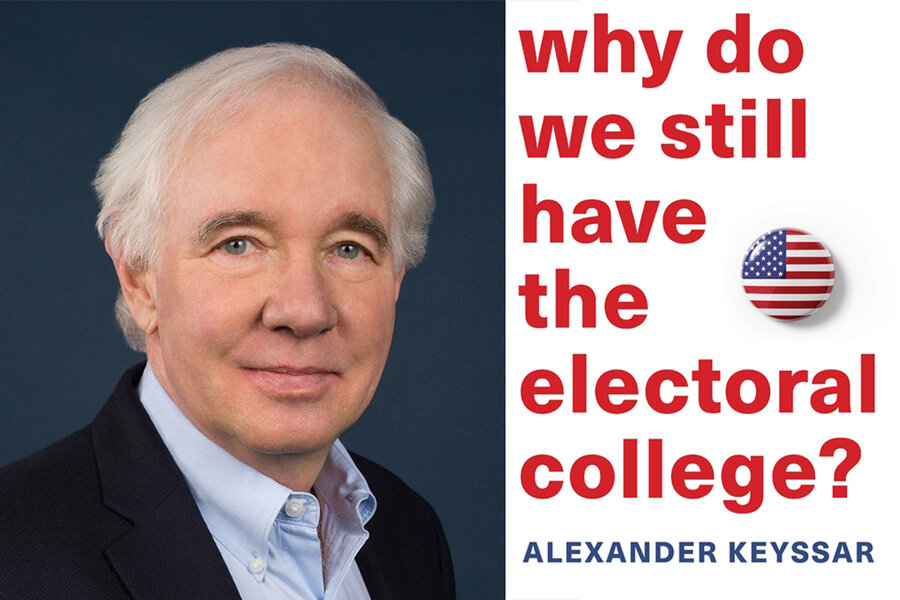

Q&A with Alexander Keyssar, author of ‘Why Do We Still Have the Electoral College?’

Loading...

It’s the question many voters ask themselves every four years: Why elect America’s president with a system as arcane as the Electoral College? For an institution so unpopular, it has proved surprisingly durable – surviving more than two centuries of complaints and confusion.

Alexander Keyssar, a professor of history and social policy at Harvard Kennedy School, attempts to answer that question in his book “Why Do We Still Have the Electoral College?” Narrating its history from the U.S. Constitutional Convention to today, Professor Keyssar explores how the system came to be, and how it has lasted.

With the country approaching another election in November, Professor Keyssar spoke with the Monitor about his book.

Q: In the book, you discuss why the Electoral College still exists – not whether it should. Why take that approach?

There have been many, many books and articles on the pros and cons, and I don’t think that I or anybody else has much to add to that debate. What grabbed me was the question that is the title of the book: Given how problematic the Electoral College is, how has it endured? It’s also the question I think several hundred million Americans ask themselves every year – why do we still do this?

Q: If it’s so unpopular, how did we get the Electoral College in the first place?

When they gathered in Philadelphia in 1787, the framers really didn’t know how the president should be chosen. The default position was that Congress would choose, but all sorts of other ideas were proposed. One proposal was to have the governors choose the president. Another was to have some sort of independent electors. They also discussed the possibility of a national popular vote. But they couldn’t come to an agreement.

At the end of the summer they took a week’s vacation and left a committee in charge of straightening it out. It was that committee which came up with the idea.

Q: How long did it take for people to start looking for something better?

Even in the 1790s, the first elections, there were signs that what they had designed was not working smoothly. What was also happening right away was the formation of [political] parties. And when you start getting these partisan interests, they start gaming the system – for example, shifting from winner-take-all votes to district elections. The dissatisfactions with the system were so great that between 1813 and 1826, constitutional amendments to significantly revise the electoral system were introduced in every Congress. Four of those constitutional amendments were actually passed by the Senate by the requisite two-thirds majority. One year it was passed by the Senate and failed by just a couple of votes in the House.

Q: Why has the Electoral College survived despite so much pushback?

There are three pieces to the answer and they’re all important. One is that partisan factors intervened repeatedly. Parties who thought they had an advantage with one system didn’t want to get rid of it. The second factor is that the institution was sufficiently complicated that changing any one part meant that you had to change other parts. That made it more difficult to reach consensus. The third factor is that between the 1870s and the 1970s, the white South fiercely opposed the adoption of a national popular vote because its leaders were convinced that would reduce their power and jeopardize the system of white supremacy they had put into place.

Q: What do you make of the partisanship that helps to keep the Electoral College alive?

As polls have shown since the 1940s, the American people have been significantly more in favor of reform than their political leaders. There is a common-sensical view among people in a democratic country that the person who wins the most votes should become president. The resistance to reform comes much more from the professional politicians who are calculating their partisan interests. Politicians who have thrived in a particular electoral system are often the people least likely to want to change the system.