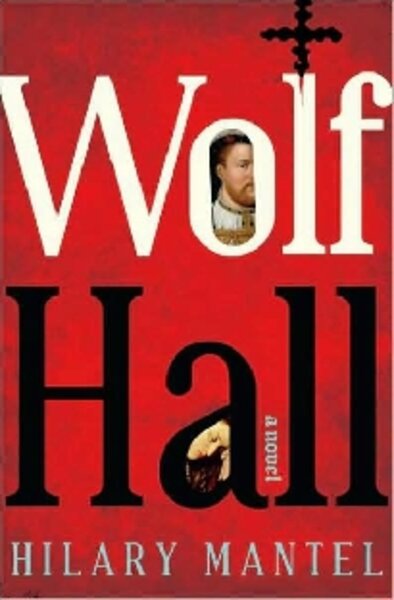

Wolf Hall

Loading...

Call it the rise of the antihero. Last year, the prestigious Booker Prize for best contemporary British fiction went to “White Tiger,” the story of a brutal, scrappy survivor from India’s under class. This year, the Booker goes to Wolf Hall, the portrait of a scheming brawler who pulled himself from the lower rungs of Tudor England all the way up to its chief palaces, a man described as “rather like one of those square-shaped fighting dogs that low men tow about on ropes.”

That would be Thomas Cromwell, chief minister to Henry VIII. Just call him the pit bull in jerkin and hose.

But Hilary Mantel, historian, novelist, and author of “Wolf Hall” is more nuanced than that. She wades into the dark currents of 16th-century English politics to sculpt a drama and a protagonist with a surprisingly contemporary feel.

“Wolf Hall” begins with Cromwell as a lad, lying half dead on the cobblestones, as the result of a savage beating from his father. The boy runs for his life.

The next time we meet him, he is fix-it man and chief adviser to England’s powerful Cardinal Wolsey. As the story proceeds, we are made to understand that in the interval the boy has become a force to be reckoned with. He has sojourned widely on the Continent, learned to speak a half dozen languages, and made his fortune in textiles and trade.

Along the way, he has also honed an eclectic but extremely useful set of skills. He can recite the New Testament and any number of secular poems by heart. He can argue theology with priests. And he can make kings laugh. As Mantel sums up the public opinion of Cromwell: “With animals, women and timid litigants, his manner is gentle and easy; but he makes your creditors weep. He can converse with you about the Caesars or get you Venetian glassware at a very reasonable rate. Nobody can outtalk him, if he wants to talk.”

An ability to talk to women proves quite useful to Cromwell when the tides turn in English politics and the woman whom Henry VIII longs to wed – Anne Boleyn – becomes a power broker. Wolsey, who picks his sides badly and fails to take Boleyn seriously, goes down, but Cromwell, his former right-hand man, only rises higher.

The bulk of the novel deals with the long interval, from 1525 to 1533, during which King Henry battles the Catholic Church, hoping for freedom from his first wife, Katherine. Much of the book is a thicket of names, alliances, and family entanglements taken directly from history. Mantel is considerate enough to provide family trees and charts of characters in the front of the book, but for those of us less well schooled in English history, keeping it all straight can be a challenge. (It’s not made any easier by the fact that, as Mantel blithely puts it, “Half the world is called Thomas” – and so are at least a half dozen of the book’s characters.)

Fortunately, the interest quotient of the plot easily outweighs any irritation with that challenge. Mantel does an excellent job of rendering both the tedium and the tension surrounding Henry’s long stand-off with the church. Lives and reputations are at stake – as is nothing less than the future of England – and we are never allowed to forget this.

Also, Mantel, an expert in the school of “show, don’t tell” writing, knows how to bring a character alive. She builds Cromwell with layers of detail accrued from multiple viewpoints. We see him jousting with ambassadors, gently teasing an imprisoned princess, and worrying about the character of his son.

Henry VIII and other historic figures flit in and out of the narrative and we are allowed unusual angles on them as well. (One of my favorite: a quick sketch of Henry discovering that his longed-for heir, Anne Boleyn’s first child, is actually a girl: “It is magnificent. At the moment of impact, the king’s eyes are open, his body braced for the atteint; he takes the blow perfectly.” And then there is the subsequent portrait of the infant Elizabeth, England’s future queen: “an ugly, purple, grizzling knot of womankind, with an upstanding ruff of pale hair and a habit of kicking up her gown as if to display her most unfortunate feature.”)

Mantel is also good at fleshing out her story with glimpses of the large world surrounding her characters. Seagulls cry, smells of freshly baked bread infuse the air, and hungry children hawk inexpensive wares. Animals, too, enliven the tale with their presence at surprising moments: the Chancellor of England strokes a lop-eared rabbit with snowy fur, the horses of courtiers in conversation bend their necks and flick their ears, Cromwell makes a pet of a rough-coated cat with golden eyes.

Such touches lend a fresh dimension to historic scenes too often relegated to either dry or highly mannered recitations. “Wolf Hall” is sometimes an ambitious read. But it is a rewarding one as well.

Marjorie Kehe is the Monitor’s book editor. You can follow her on Twitter at twitter.com/MarjorieKehe.