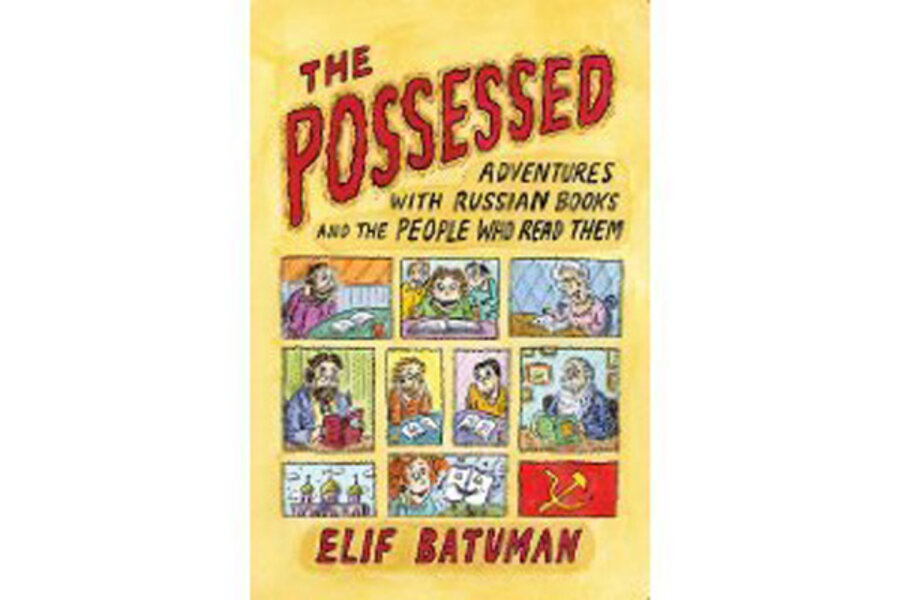

The Possessed

Loading...

It’s not often that one laughs out loud while reading a book of literary criticism. In seven delightfully quirky essays that combine travelogue and memoir with criticism, Elif Batuman’s The Possessed takes us on an unconventional odyssey through the world of Russian literature in search of “direct relevance to lived experience, especially to love.”

Batuman, a first-generation Turkish-American, was educated at Harvard and Stanford, where she now teaches part time. What’s refreshing about her writing is her wonderful sense of the absurd and her willingness to venture into out-of-the-way corners – both geographically and intellectually – and to admit when she’s hit a dead end.

Rare among academics, Batuman writes about her literary awakening as a process. In this spirit, she describes her initial bafflement on first reading certain classics. Isaac Babel’s story “My First Goose,” for example, at first “made absolutely no sense to me. Why did he have to kill that goose?” she writes.

The same goes for Dostoyevsky’s “weirdest novel,” “The Demons,” whose earlier translation as “The Possessed” supplies her book’s title. Why? It concerns “the descent into madness of a circle of intellectuals in a remote Russian province: a situation analogous, in certain ways, to my own experiences in graduate school.”

After an engaging plot summary, Batuman describes how she came to understand that “The Demons” was more than just a flawed novel. “Graduate school taught me this. It taught me through both theory and practice.”

Among the literary theories Batuman discusses – with admirable clarity – are “mimetic desire” and “conversion narratives,” in which authors redeem tales of sinfulness and decadence with moralistic endings. But it’s her tests of these theories in the context of her own life that reverberate. A classmate from Zagreb treats Batuman as if she’d “stolen his soul” after they end up in bed together, breaking seven years of celibacy for him. Like Dostoyevsky’s antihero Stavrogin, Matej exercises an unhealthy, destructive magnetism over others. Still, Batumen is horrified when he enters a Carthusian monastery in Slovenia, thereby enacting his own conversion narrative.

Batuman spends a summer in Samarkand studying Uzbek language and literature, which she writes about years later in an overly long, three-part memoir oddly interspersed among the book’s more trenchant essays – an indication that, despite the passage of time, this experience remains, “Like a Christmas ornament without a Christmas tree, there was nowhere to put it.” She eventually realizes that, “Uzbekistan wasn’t a middle point on some continuum between Turkishness and Russianness,” and that reading obscure literature she only half-understood had lost its charm.

Still, Samarkand is a significant way station on Batuman’s journey toward “bringing one’s life closer to one’s favorite books.” Following authors’ trails requires funding, which she seeks in sometimes bizarre scholarly grants and New Yorker assignments.

The latter takes her, among other places, to St. Petersburg, Russia, in February 2006, to report on a historical replica of the House of Ice that Peter the Great’s niece, Empress Anna Ioannovna, commissioned in 1740 for the wedding of two court jesters, who were forced to spend their nuptial night inside it. The replica, a bizarre attempt to boost winter tourism, raises all sorts of questions for Batuman about the original, which she sees as an embodiment of what great literature, with its redemptive conversion narratives, works so hard to avoid: “the glorification of immoral, useless decadence.”

Part sleuth, part pundit, Batuman both plays the game of literary exegesis and skewers it. In her funniest piece, “Babel in California,” originally published in 2005 in the magazine n+1, the dinner conversation at an international conference at Stanford on the early 20th- century Odessan-Jewish writer Isaac Babel evokes the sublime silliness of Tom Stoppard’s “Travesties.” When a colleague maintains that Babel’s “Red Cavalry” cycle would never be totally accessible to her because of its “specifically Jewish alienation,” Batuman responds, “Right.... As a six-foot-tall first-generation Turkish woman growing up in New Jersey, I cannot possibly know as much about alienation as you, a short American Jew.” It goes right over his head.

In the title essay, Batuman, in Florence, Italy, to research an article on a Dante marathon, visits a Stanford classmate, a poet who says that if he were to start over today, he’d study Islamic fundamentalism instead of literature. Not so for Batuman. “If I could start over today, I would choose literature again. If the answers exist in the world or in the universe, I still think that’s where we’re going to find them.”

Yes!

Heller McAlpin, a freelance critic in New York, is a frequent Monitor contributor.