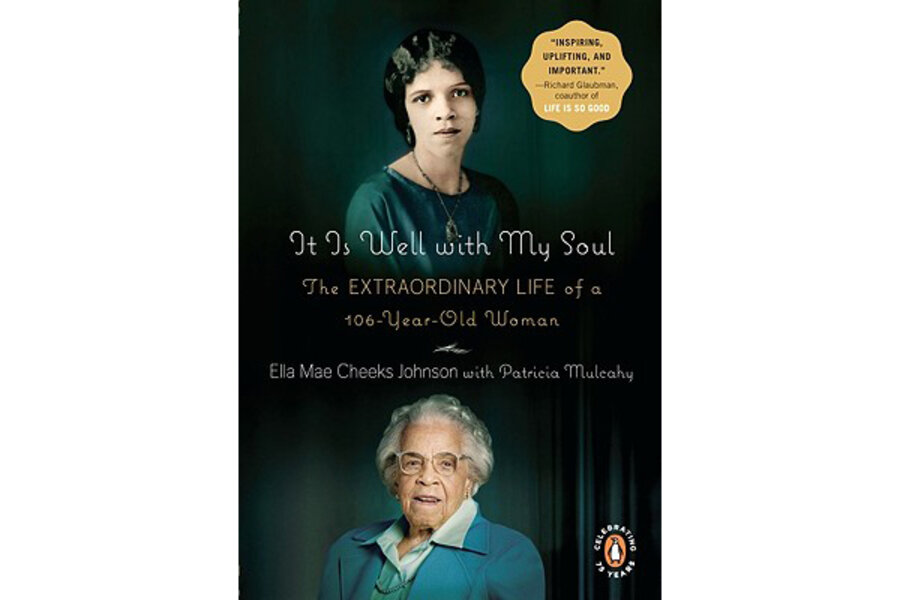

It Is Well with My Soul

Loading...

“Some of the things in this book happened a hundred years ago.... I never anticipated having to remember all this,” says Ella Mae Cheeks Johnson as she opens her memoir, It Is Well with My Soul: The Extraordinary Life of a 106-Year-Old Woman, written with Patricia Mulcahy. Über-centenarian Johnson recalled more than most people half her age. Sadly, her readers can’t expect a sequel to her delightfully plain-spoken memoir as she passed away on March 22. (The memoir’s original publication date in May was quickly pushed up, making the book available now.)

Born Jan. 13, 1904, in Dallas at a time when “black citizens had no official papers,” Johnson was raised by her next-door neighbors, the Davis family, after the death of her mother. “Everything in the Davis environment left me certain I was loved,” she writes.

Yet despite a nurturing home environment, in many ways Johnson’s early years were harsh ones. Growing up poor but never needy, she couldn’t escape the helpless humiliation faced by “blacks, or Negroes, or colored people, or whatever they called us.” She watched as “some things were out of Papa’s control,” how adults “had to lie in order to survive,” and the “many ways in which we were put in our place in the Jim Crow South.”

Johnson graduated salutatorian to her valedictorian best friend from Dallas Colored High School and, in 1921, entered Fisk University, a historically African- American college in Tennessee. During an art class in her senior year, Johnson painted a copy of a picture based on the biblical story of the The Good Samaritan: “My entire life has been driven by my emotional and spiritual response to the picture, and the message of compassion it communicates,” she writes.

Johnson finished Fisk six months later than anticipated because she missed a semester participating in a college-wide boycott orchestrated by legendary Fisk graduate W.E.B. Du Bois who “agitate[d] for the rights of his people, whatever they wanted to call us – Negro, colored, black.” Lest you think Johnson a lemming, even in a clear battle for civil rights, she feistily adds, “I don’t follow just because someone else decides to lead.”

After working briefly for the Congregational Church in Raleigh, North Carolina, Johnson arrived in Ohio – where she would live the rest of her life – as one of only two minority students admitted each year at Western Reserve University’s School of Applied Social Science. Decades later, the school was renamed Case Western Reserve University, and Johnson was recognized (until her recent death) as the oldest living African-American graduate of CWRU.

Graduate degree in hand, Johnson devoted her entire career to helping others as a social worker. She married the “love of her life,” Elmer Cheeks, in 1929, promising “to love, honor, and cherish” rather than the expected “love, honor, and obey” because “this is just what I saw as fair.... I would not agree to ‘obey.’ I was a grown woman, not a child.” Cheeks died just 12 years later, but the couple’s “very strong love affair” produced two sons, Jim and Paul: “Trying to be both mother and father, I may have been too hard on my sons at times. But they are now loving and devoted fathers as well as successful professionals. So it all came right in the end.”

With retirement in 1961, Johnson began to travel the world “in earnest,” journeying to five of the planet’s seven continents. “[N]othing [is] more important than a broad vision of the world,” she insisted. Along with vision, Johnson urged mutual respect. “I don’t have to accept what you think; but I will respect your right to go your own way.... I believe in asking, listening, and allowing people to come to their own judgments.”

In many ways, her life's journey was lengthy. She traveled from the fear she experienced as a young girl watching unjust humiliations to – at the age of 104, buried under a sleeping bag in her wheelchair to ward off freezing January temperatures – bearing witness to the inauguration of the country’s first African-American president. “Though we still need change, we also need to celebrate how far we’ve come,” she reminds us.

To say that Johnson’s life story is inspiring seems mere understatement. She learned to drive at age 70, loved to read throughout her life (“The 9-11 Commission Report” and “The Confessions of an Economic Hit Man” were recent selections), and raised $3,000 for AIDS patients in Africa at her own 100th birthday party in the middle of a blizzard: “People don’t always know what older people can accomplish,” she says without irony.

One of Johnson’s caretakers in her assisted living home, remarks of Johnson’s unwavering determination, “‘ ‘Warrior trumps worrier.’ ” Indeed, through an entire century of vast challenges and immeasurable change, Johnson moved forward in stalwart fashion. In 1973 she heard a Ghanian congregation singing the words, “It is well with my soul.” These many years later, as readers and supporters, we can all join her in saying, “So it is!”

Terry Hong is media arts consultant at the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Program. She writes a Smithsonian book blog at http://bookdragon.si.edu/.