Classic review: Girl with the Pearl Earring

[This review from the Monitor's archives was first published on Dec. 30, 1999.]

Johannes Vermeer, the 17th-century Dutch master, only produced one or two paintings a year during his brief career. But recently, novels about his work are piling up faster than that.

It started with "The Music Lesson," by Katharine Weber, a quiet suspense novel about IRA terrorists holding a Vermeer for ransom. Then this fall, Susan Vreeland followed a single Vermeer painting from the present day through all its previous owners in "Girl in Hyacinth Blue."

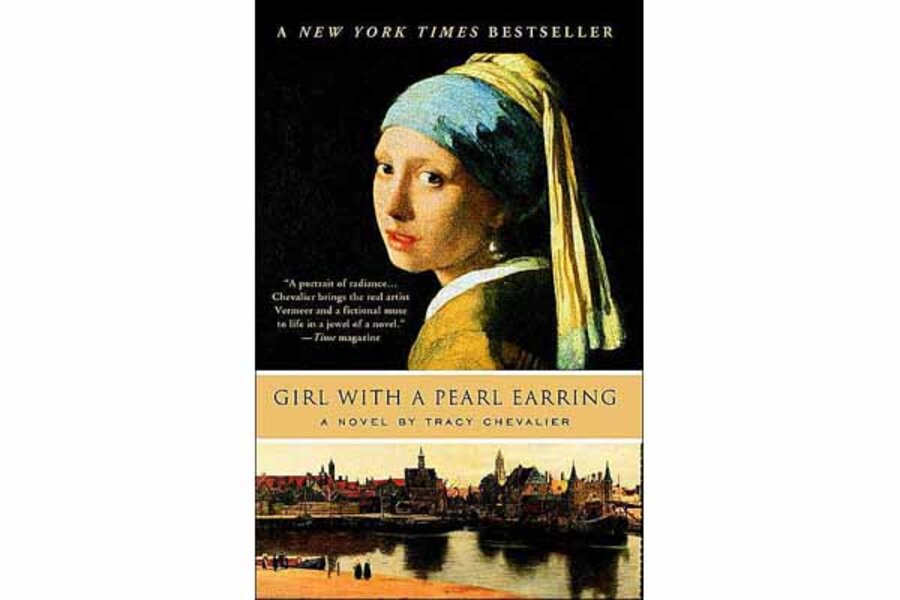

And now, here comes Tracy Chevalier's affecting novel, Girl with a Pearl Earring, about a precocious maid in Vermeer's household.

Who's this guy's publicist? For a man who left no more than 35 paintings, he's suddenly getting plenty of attention outside the museums. Perhaps it's the paucity of information about Vermeer's life or the small number of exquisite paintings that makes his work such an attractive subject for novelists.

Chevalier's story shares some of the striking qualities of Vermeer's paintings. Her subject is a single woman caught in a private moment. Like the Dutch master, she's fascinated by the play of light, the suggestive power of small details, and the subtle thoughts beneath placid expressions.

The story is told by Griet, a young woman in Delft. Her family, never prosperous, has been thrown into desperate circumstances by a recent kiln accident that blinded her father. While her young brother is sent to a harsh tile factory, Griet finds work as a maid in the home of Johannes Vermeer.

Now and then Chevalier's style seems self-consciously rich. Her poor, illiterate narrator sounds at times as though she's earned a master's degree in creative writing, as the author has. But, that aside, Chevalier re-creates common life in Delft with fascinating authenticity. The smells of the marketplace, the drudgery of laundry, the subtle tensions between servants – it all comes across here viscerally.

Vermeer's house is full of his own children and other people's paintings. Griet finds it something of a land mine. Their Roman Catholic faith is an unsettling mystery to her. The painter's daughters are eager to test her authority. His wife resents the competition for her husband's attention. And the careful old mother-in-law is willing to do anything to increase Vermeer's meager artistic output.

With wonderfully effective restraint, Chevalier captures the glances and brief comments that gradually lead Griet into her master's studio, his painting, and finally his heart.

Any sign of intimacy with Vermeer's work would mean certain dismissal by the painter's captious, continually pregnant wife, but Griet can't help but stare at his haunting portraits when everyone else has gone to bed.

Though they're very quiet moments, the most exciting scenes are those of Griet slowly learning to see with greater perception and understand the nature of light and shadow. Soon, she's making crucial recommendations to the master about shading, composition, and color.

When Vermeer's raunchy patron insists on a portrait of Griet, he forces a crisis that exposes the thicket of affections and jealousies coursing below the surface of this house.

"I wanted to know the man who painted like that," Griet thinks one day while dusting Vermeer's studio. That knowledge is ultimately denied her – and us – but his elusive quality seems as accurate as the rest of this luminous novel.

*Ron Charles is a former Monitor book editor.