Bobby Fischer

Loading...

As a public figure, the notorious anti-Semite Bobby Fischer has a lot in common with Sandy Koufax, one of the most famous Jews ever to play professional sports. Both Fischer and Koufax walked away from their games at the peak of their powers and left millions of onlookers aglow with memories of their skill and artistry. Koufax retired as a Cy Young Award-winner and strikeout king. Fischer won the World Chess Championship in 1972 and then forfeited his title rather than defend it.

Fischer, of course, had a repulsive second act in which he returned to tarnish these memories. His public hatreds of Jews and the United States of America brought him occasional notice in the years leading up to his death in 2008 – and also after it, when he was briefly exhumed for a posthumous DNA test.

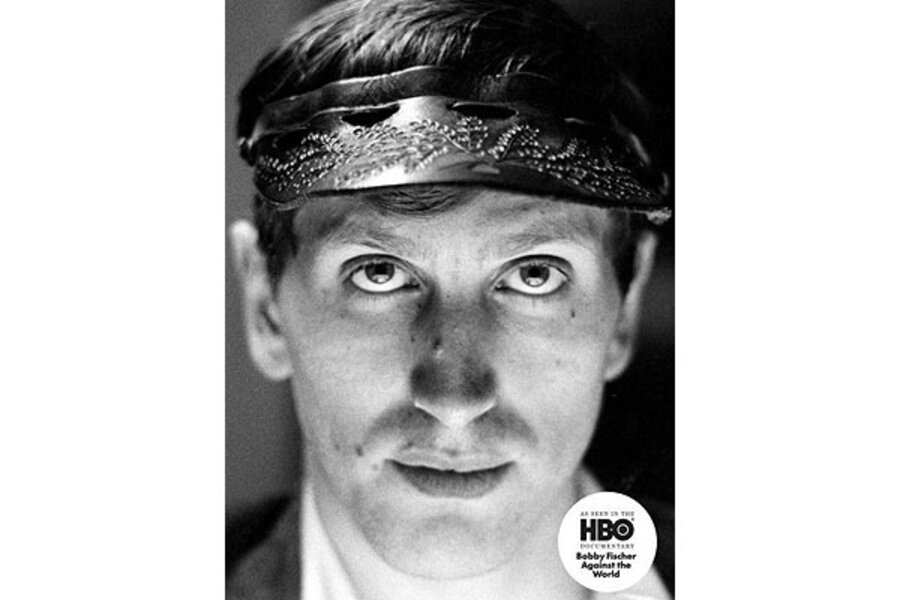

Now photographer Harry Benson has published Bobby Fischer, a collection of pictures taken of Fischer during the earlier, happier time of his ascent. They remind us of how Fischer’s charisma made him America’s first and only chess celebrity.

Benson was not a chess fan. Indeed, he barely knew how to move the pieces. But the reclusive Fischer granted him unprecedented access in 1971 and 1972, during the period leading up to and encompassing his triumph over Boris Spassky. Fischer’s virtually single-handed triumph over Spassky and the rest of the USSR’s powerful chess establishment resonated around the world. His achievement was immediately painted as a symbolic victory in a small-scale version of the Cold War.

Benson’s "Bobby Fischer" presents a marvelous compendium of intimate photos of the grandmaster working and relaxing, in motion and at rest, grimly focused and at lank-limbed leisure. There are many good documentary photos on display here, such as a vivid pre-game handshake between Spassky and Fischer, but the best and most evocative pictures in this extraordinary book are of Fischer alone. Benson, a longtime photographer for Life Magazine, notes in his brief accompanying remarks that Fischer preferred the company of children and animals to that of other adults. His solitude eventually became pathological, but here it encases him in photographic amber, kissing a dog or gazing meditatively out onto a lake in the Icelandic night.

Fischer’s competitiveness, coupled with his suspicion of strangers, meant that he kept himself to himself, his depths unplumbed and mostly unseen by others. But Benson’s lyrical portraits – including, amazingly a couple of informal nudes – break down more of Fischer’s barriers than anything that has been written about him to date. Images of Fischer gazing intently at chess positions on his ubiquitous pocket set, but also playing ping pong, mugging underwater in the pool, lazing in the sauna, even being nuzzled by a wild horse in an Icelandic meadow – together, these pictures capture a brooding but also magnetic personality, an attractive man with an intense stare and a bell-ringer grin: in other words, a star.

As a star, Fischer followed the lead of Greta Garbo. Shortly after Benson photographed the new world chess champion slumped on his bed in understated triumph, exhausted but clutching his winner’s check, Fischer disappeared from the public eye, as did Garbo. He stayed away for 20 years, only to emerge in the unshakable grip of an ugly mental illness.

Benson’s beautiful and evocative portraits help us recall the titan at his height. The pictures bring back the memories of Fischer’s great achievement, but they are unavoidably tinged with our own retrospective sadness that his obsessions took him from celebration to disgrace.

Leonard Cassuto is a book critic for The Barnes & Noble Review.