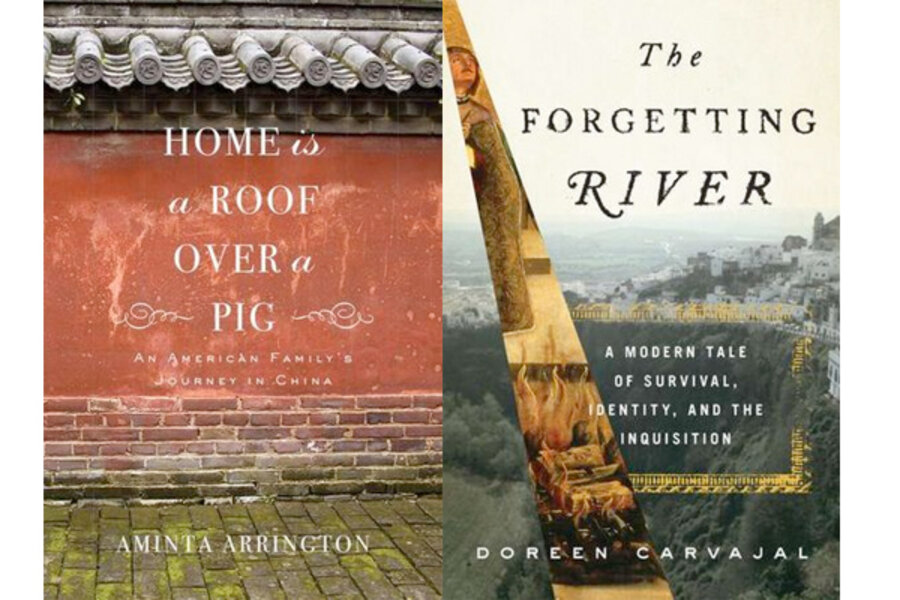

'Home is a Roof Over a Pig' and 'The Forgetting River'

Loading...

Who are we? Are we best defined by the language we speak, the schools we attend, the religion our parents subscribe to, or the country that offers us citizenship? Or does it require a blend of all of the above and more to determine our identities?

Two very different American writers were propelled to opposite corners of the globe in their separate quests to answer such questions.

In Home is a Roof Over a Pig, Aminta Arrington didn’t move to China looking for her own roots. Instead, she was seeking out the cultural heritage of her adopted daughter. Three years earlier, she and her husband had adopted a charming Chinese toddler they named Grace. But the first time they removed Grace’s clothes and replaced them with “the cutest outfit we had brought with us and a fresh Pampers,” Arrington worried that they were changing something more fundamental – “her identity.”

It is the search for Grace’s roots that prompts Arrington to take a teaching job at a rural Chinese university and move her family there. “We are in the real China,” her husband notes the day they arrive. Arrington concurs – and it’s just what she wants: “A China of raising children, taking crowded buses to work, sitting on stools playing Chinese checkers, hand-washing laundry and hanging it out the window.”

The family of five – Arrington and her husband, their other two children, and Grace – crowd into a tiny concrete bunker of an apartment. The children enroll in public school and Mom and Dad join the university faculty. Slowly, as months and then years pass, the Arringtons absorb the language, adapt to the culture, and begin to belong.

Arrington is a sunny (“Cynicism and I cannot breathe the same air”) and energetic guide to today’s China – where Volvos glide among donkey carts and the Kitchen God coexists with Marxism. It is here that Arrington – while seeking out her daughter’s roots – also discovers “the person I was created to be.”

More darkly poetic is The Forgetting River, the memoir in which International Herald Tribune and New York Times correspondent Doreen Carvajal unspools her own story of a search for family roots. Carvajal grew up in California convinced that her family line was rooted deep in Latin America – only to discover that the Carvajals were probably Sephardic Jews forced out of Spain during the Spanish Inquisition. Carvajal takes her family to live in “the craggy rock of Arcos de la Frontera” in Spain where she hunts out hints of family histories “discarded and rewritten.” Her quest takes her back centuries and across Europe as far as Brussels and Belgrade, Serbia.

So effectively were the Jews and their history wiped out that Carvajal must decode the faintest of clues hidden in centuries-old bell tones and aging canvases. When she finally finds, in Barcelona, Spain, the site of a 3rd-century synagogue, its ancient stones now house a dry cleaner and “junk storage site.”

Further complicating her search is the fact that Carvajal isn’t even sure she wants to embrace a new religious identity. Raised as a Roman Catholic, part of her wants to cling to “lacy white Communion veils ... pink rosary beads ... and the dark, hushed confessionals.”

But she is driven onward by “what the Spanish call añoranza, a longing for home, to be whole.” If she doesn’t entirely arrive there, she at least discovers a deep pleasure in the journey.

Marjorie Kehe is the Monitor’s books editor.