The Big Truck That Went By

The numbers are not inspiring: Six months after the United States pledged $1.15 billion to Haiti in response to the 2010 earthquake, not one dime had arrived in the country. Three years after the magnitude-7.0 quake, with 100,000 Haitians still living as squatters, a $15.7 million Best Western is one of the country’s most significant new building projects.

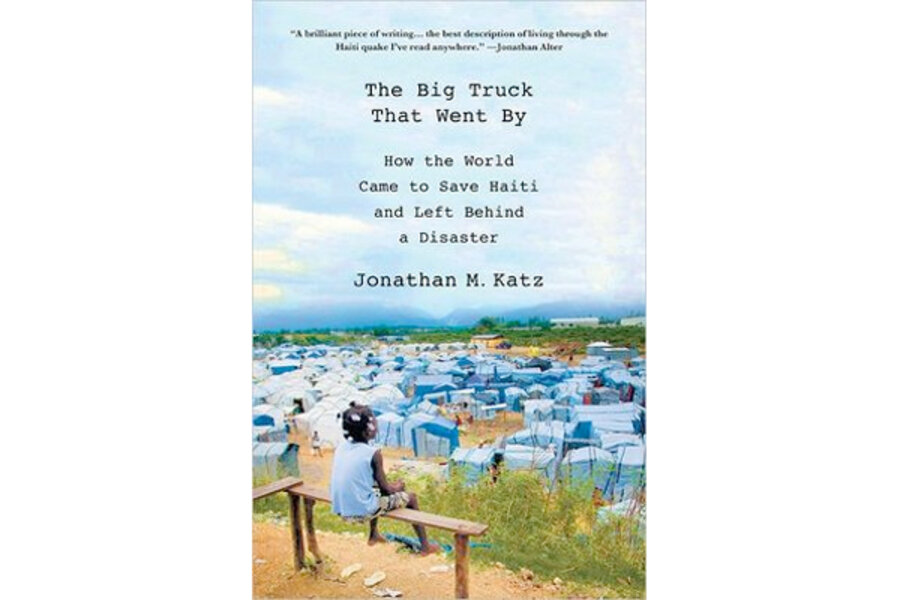

A book telling only this story would be worth reading. The Big Truck That Went By, by former Associated Press writer Jonathan Katz, does this and much more.

Katz starts with what becomes a parable: the story of a private school called La Promesse (“The Promise”), built in the wealthy Haitian hilltop suburb of Pétionville but attended by kids from the slum below. It was no secret that the school was poorly built. Even before it collapsed in 2008, killing 93 (mostly children), “parents living along the ridge could see what was happening, but they were in no position to complain.” Anyway, “most had built their homes the same [shoddy] way.”

In fact, most of the country was built that way, as Katz learned firsthand. He was living in that suburb – the only American journalist permanently based in Haiti – when the earthquake struck in January 2010. His retelling of that moment is gripping. He heard a rumble; his bed shook. “Medicine bottles, suntan lotion, and bug spray shimmied on the round black table I always left cluttered because I’d never counted on staying in Haiti long enough to need a dresser.”

Everything is thrown against everything else. “There was a contest between the up and down and the side to side,” he writes. Minutes later, a colleague gets him out.

Katz doesn’t linger long on his personal story. Just a few pages later, we’re listening to the pitched wails of mourning. “I had only ever heard Haitian women make that sound, and only ever standing before the worst thing in the world: the collapse of a home, the death of a child,” Katz writes. “Now it came from everywhere.”

Haiti had seen its share of natural disasters, but the wealthy had rarely suffered. This earthquake leveled off economic advantage: “[G]reat government ministries and posh hotels had crumbled alongside the meanest cinder-block homes. The homes and apartments of embassy workers had collapsed along with the supermarkets and gyms they had frequented.”

But the equalizing power of nature lasted only until the world powers intervened. Foreign rescue privileged privilege: In one of his most heartbreaking stories, Katz writes about a young girl Haitian workers didn’t have the tools to rescue. Just over the hill, at a posh hotel favored by foreigners, six rescue teams led by an ex-Army Ranger were assisting trapped hotel guests.

In Haiti it all depends on whether you live in or outside “the blan bubble.” “Blan” is Creole for “white,” but it denotes all foreigners, whose power and means allow them to live in near-isolation from the Haitians they’ve come to help.

What stands out in this critique of expat communities and development is Katz’s declarative tone. He refuses judgment, even as his observations indict the system in which they work. He forces a confrontation with the hubris and double standards of international aid, yet he’s anything but haughty.

There’s deft background on Haiti here, and coverage of the postelection quake. There’s original investigative reporting about land grabs after the earthquake and there’s a chapter on cholera in Haiti and the UN’s acrobatic denial of culpability for the epidemic. There’s only passing mention of sexual violence (perhaps the book’s biggest weakness).

What there is, however, is a critique made more powerful by the perspective it includes. Katz combines the knowledge of Haiti he built over 3-1/2 years working there with his understanding of outsiders’ clichés about poor, impoverished countries.

He writes about the assumption pervasive in aid work, that governments are too corrupt to handle funding themselves. “The irony was that, by keeping the money under their own control, the donors reinforced the perception of systemic Haitian corruption,” Katz writes. Donors’ irresponsibility reinforced Haitians’ view of the same: “If money was pledged but not received, [Haitians] assumed their leaders had stolen it.”

If there is a hero in this book, it may be the beleaguered and prophetic former Haitian president, René Préval. After the collapse of the school in Petionville, Préval had given an ill-attended talk at the United Nations, warning that his country was structurally unsound. “He had known, he had warned, and he had been powerless to stop it.”

International assistance since the earthquake hasn’t altered that reality. Instead, it has reinforced it. The most powerful people in Haiti are foreign donors, unaccountable to and unelected by Haitians, who, like the parents living below La Promesse, are made mere observers of the disasters they too easily see coming.

Jina Moore is a Monitor correspondent.