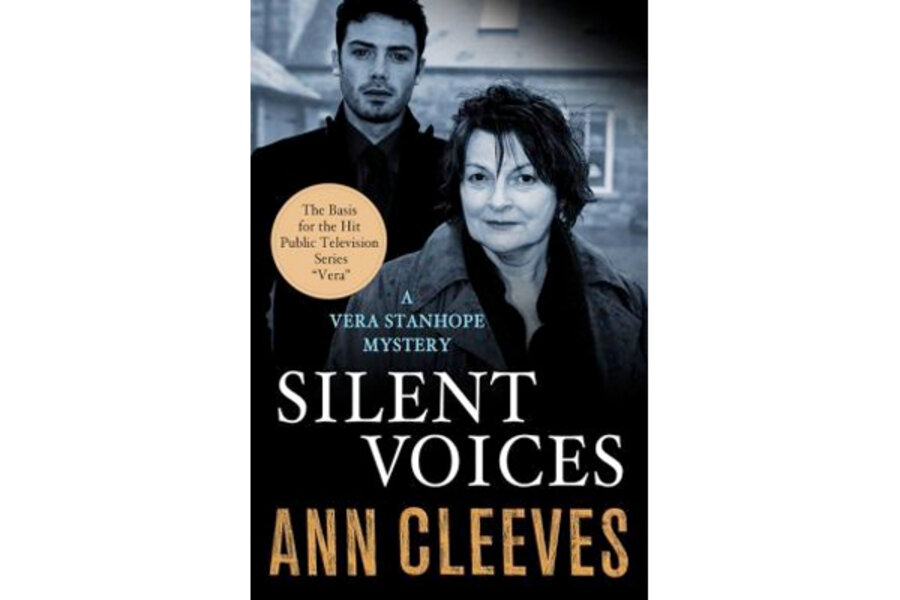

Silent Voices

The fictional female detective has altered greatly since the heyday of the genteel village lady who stumbles upon murder. And the dull, small world she inhabited, masterfully evoked by writers such as Patricia Wentworth and Sheila Radley (a personal favorite), lies buried under a gooey avalanche of theme mysteries (cookies, cats, crafts – take your pick). But just when it seemed that any sleuthing heroine must be either a perky quilter or a tattooed avenger, along comes Detective Inspector Vera Stanhope.

Hardly genteel, Vera is nonetheless a reassuring sight to readers of Ann Cleeves’s Silent Voices, if not to those under the DI’s scrutiny. “When he saw her approaching, she noticed the surprise and disappointment on his face. Perhaps he’d been hoping for Helen Mirren,” Vera observes of one encounter. An earlier interview begins the same way. “She was confused, Vera could tell,” we read of snooty Mrs. Eliot, “The car Vera was driving was large, new, and rather expensive. One of the perks of her rank. Mrs. Eliot would consider it the sort of car to be driven by a successful man. Yet Vera was large and shambolic, with bare legs and blotchy skin.... Vera looked poor.”

Like Reginald Hill’s beloved protagonist Andy Dalziel, Vera is cunning and irreverent. “God,” she thinks, listening to the outpourings of one witness, “what self-indulgent drivel. I’d rather spend time with an honest criminal any day than with this introspective woman.” Her manner with interviewees can be indelicate. “Don’t piss me about,” she wearily advises a recalcitrant householder. “I’m not in the mood … let me in so that I can take the weight off my legs.”

Vera would not be caught dead in a gym, but that is where we meet her in "Silent Voices" and where she discovers the first murder victim. (Cleeves enjoys these little ironies). Jenny Lister, a social worker, has been strangled, and at first no explanation can be found in Lister’s supremely organized life. There are, however, some odd coincidences. An ex-subordinate of Lister’s, Connie Masters, who was at the center of a child drowning case, recently moved, unwittingly, to Lister’s Northumberland village. Masters’s neighbor, Mrs. Eliot, lost a child to drowning decades earlier. And Lister’s daughter is engaged to Eliot’s remaining son.

The murder investigation uncovers further human connections that, in Cleeves’s hands, seem natural rather than far-fetched; Northumberland is, she reminds us, England’s least populated county. Plain descriptions vividly evoke the modest region and its inhabitants, and Cleeves’s economical style freshens even well-worn scenes such as police briefings and interrogations. Plot twists are few and satisfying.

When a second murder, for example, suggests that the past may not hold the key to Lister’s death, Vera begins to detect a new shape forming. “Lying in the bed she’d slept in as a child,” Cleeves writes of the single woman in her dead father’s farmhouse, “…images and ideas floated into her head and then fluttered away from her, like the charred tatters of paper blowing from a bonfire.”

Those tatters, of course, hold the answer and Cleeves pieces them neatly together. Vera, by contrast, remains gloriously unresolved in Cleeves’s subtle portrait. “They sat on the two low chairs, their feet to the fire,” she writes of the DI and Joe Ashworth, her young sergeant. “Vera thought this was as happy as she would ever get.” There is no need to say more.

Anna Mundow, a longtime contributor to The Irish Times and The Boston Globe, has written for The Guardian, The Washington Post, and The New York Times, among other publications.