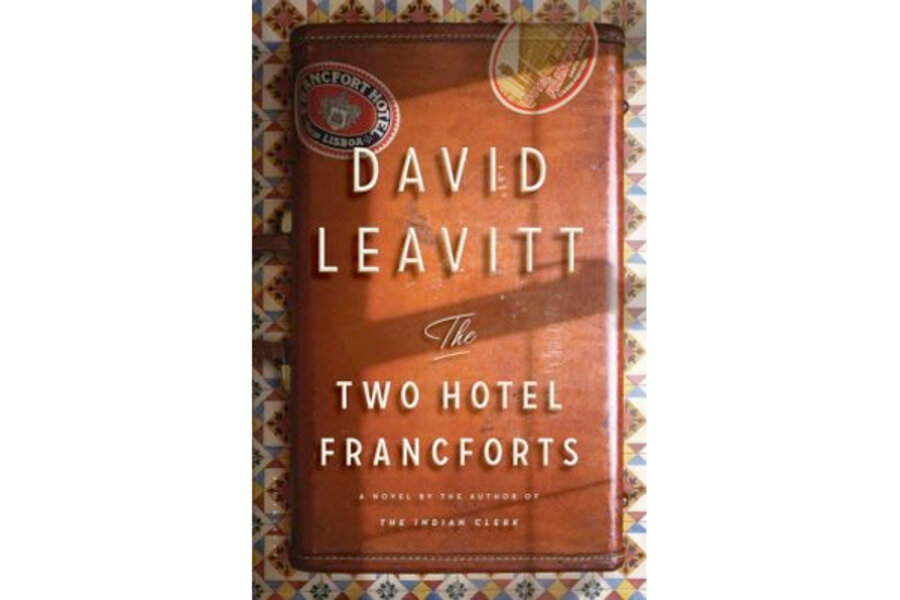

The Two Hotel Francforts

Loading...

It's hard to imagine, now that marriage equality has become almost commonplace, but David Leavitt's short story "Territory," published in The New Yorker in 1982, was the first openly gay fiction in the magazine. A sensitive exploration of tensions that arise when 23-year-old Neil brings home his male lover for the first time, the story is tame by today's standards – or even in comparison to Leavitt's 1997 novella, "The Term Paper Artist," which was pulled from publication in Esquire over what the magazine's editor called "a taste question." But in its crossover appeal to gay and straight readers alike, it helped break down the ghettoization of gay fiction. Nowadays, it sometimes seems as if it's the rare novel that doesn't have at least one gay character.

The Two Hotel Francforts, Leavitt's eighth novel, has no openly gay characters, though it features a brief but torrid homosexual affair between what not so long ago could have been simply described as two unhappily married men but now needs to be clarified as two men in unhappy marriages with women. Set in Lisbon, Portugal, in June 1940, where hordes who have fled occupied France gather to await passage to safety, it offers a different sort of crossover appeal – to readers of both historical and domestic fiction.

Spanning just a few weeks and 250 pages, "The Two Hotel Francforts" is a stylish model of narrative compression and economy. Despite the escalating Nazi threat that forms its backdrop, its focus is alienation of affection rather than annihilation.

Pete Winters and Edward Freleng, American expatriates in their early 40s, meet cute at a popular café in Lisbon when Edward accidentally steps on Pete's eyeglasses – rendering him blind to what's coming. Both men are killing time with their wives while waiting for the SS Manhattan, which has been commandeered to retrieve Americans stranded by the war. Both are also staying in the Hotel Francfort – though, as it turns out, two different hotels that share the same name because they were formerly owned by feuding brothers. The novel is Pete's account of the fortnight or so that profoundly changes the two couple's lives.

Leavitt hooks us by the third page, with this sentence: "I should mention – I can mention, since Julia is dead now and cannot stop me – that my wife was Jewish, a fact that she preferred to keep under wraps." The same paragraph ends: "For she had sworn, when we had settled in Paris fifteen years before, that she would never go home again as long as she lived. Well, she never did."

Of course our minds flood with questions, which Leavitt deftly keeps in play until the end of the book: Why was she so loath to go home? How did she die? When? Killed by the Nazis? Destroyed by her husband's dalliance with another man? Suicide? Foul play? A staged, "apparent" suicide like the one in the detective novel that Edward and his wife, Iris, are writing under their pen name, Xavier Legrand?

Julia, as described by her admittedly disenchanted husband, is not a character we're sad to see go. Upset about having to leave their elegant Paris apartment – featured in a copy of Vogue that has become dog-eared from her constant thumbing – she is "too worried about what we were losing to care about those who were losing more." This is a woman who spent her days shopping or playing a version of solitaire called, aptly enough, Beleaguered Castle.

Pete, who we're supposed to believe is a car salesman originally from Indianapolis, ignored every warning signal about Julia "until a morning came when I woke and found that the burden of her care was crushing the life out of me." Yet he still feels duty-bound to protect her and is convinced that the prudent path, considering her Jewish heritage, is to ignore her "Over my dead body" objections and insist they leave Europe while they can. By the time he learns the reason for her recalcitrance, it is too late.

If the Winters' marriage is a bad deal for Pete, the Frelengs' is even worse for Iris – though at least they appreciate each other intellectually and share a devotion to their aged terrier, Daisy. Iris, a long-necked and awkwardly tall British Raj orphan, met Edward while he was studying philosophy at Cambridge University – before he was thrown out for flouting the rules. Since leaving their "feeble-minded" daughter in a California institution near Edward's mother (who rescues her), they've spent the past 18 years flitting around Europe on Iris's inheritance. Their peripatetic existence is broken up by occasional rest cures, where the alternately dazzling and despondent (and seemingly bipolar) Edward can recover from his periodic suicidal "episodes." Their popular Xavier Legrand whodunits, including the significantly titled "The Noble Way Out," came about as a diversion during these recuperative interludes. Their marriage is sexless – unless you count their creepy arrangement, in which Iris sleeps with the men Edward craves but sends her way. Pete, both Frelengs tell him, was earmarked for Iris, but – something happened.

Leavitt's novel has some of the snap of a comedy of manners and the hard-boiled moodiness of "Casablanca." With Noël Coward's "World Weary" playing in the background, Edward and Pete drink absinthe at the Estoril casino, brush knees under the table, and discuss "this weird vitality, this sense that you can do things you wouldn't normally let yourself do" that accompanies the fear, panic, and uprootedness of wartime.

Leavitt has written of sex between men as "really a matter of exorcism, the expulsion of bedeviling lusts," and this holds true for the intense but quickly passing physical communion in "The Two Hotel Francforts." As Pete and Edward search for privacy in a city teeming with spies and refugees, Lisbon becomes a party to their affair. After taking refuge on the Bica Elevator, which scales the city's steep cliffs, Pete comments, in a sentence that could well spark a book group discussion: "Now it occurs to me that marriage itself is a kind of funicular, the regular operation of which it is the duty of certain spouses not just to oversee but to power."

Leavitt first ventured into historical fiction in 1993 with his third novel, "While England Sleeps," a homosexual love story set in 1930s England and Spain. It caused an uproar – and necessitated a revised edition – because of its unauthorized debt to Stephen Spender's 1951 memoir, "World Within World." After several books in the more contemporary vein of his earlier work, his most recent novel, "The Indian Clerk" (2007), blended fact and fiction to explore the relationship between two great early-twentieth-century mathematicians, one of whom he characterizes as a closeted gay man, the other his Indian protégé.

Despite its wartime setting and its concern with issues of guilt and responsibility, "The Two Hotel Francforts" offers a bouncier read than Leavitt's previous novels, with an especially satisfying, almost jaunty ending. A book group might want to start by considering how Leavitt uses historical fiction not just to illuminate the past but to shed light on contemporary issues – including how different are the options for men like Edward today.

Heller McAlpin is a New York-based critic who reviews books for NPR.org, The Los Angeles Times, Washington Post, San Francisco Chronicle, The Christian Science Monitor, and other publications.