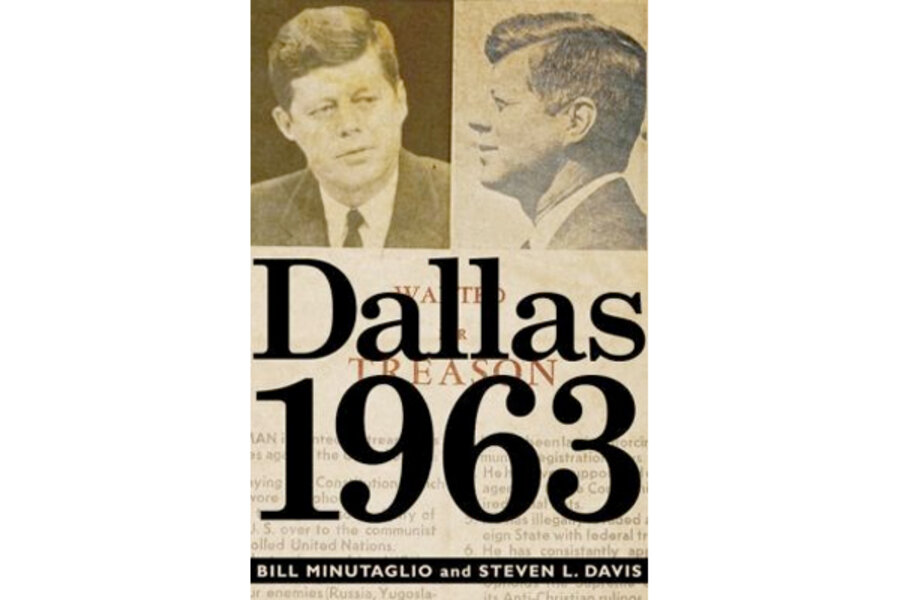

Dallas 1963

Loading...

As the 50th anniversary of President Kennedy’s death looms, a raft of books exploring the tragedy in Dallas are hitting their publication dates. Bill Minutaglio and Steven L. Davis aim to make their title, Dallas 1963, distinct from the rest by turning their attention from the assassination itself to the toxic political climate of Dallas. What kind of city would produce a president’s assassin?

To answer that provoking question, the authors – both Texans – paint a series of detailed portraits of the agitators in Dallas who, they argue, created the poisonous far-right milieu behind one of the American century’s most catastrophic events. Among them are W.A. Criswall, the hot-headed pastor of the world’s largest Baptist congregation who preaches segregation. There is H.L. Hunt, the billionaire oil baron who self-publishes a book meant to inspire Americans toward the promise of a land where the wealthy have more votes than anyone else, and the bottom forty percent of taxpayers have no votes at all. And there is Ted Dealey, the obsessive publisher of the Dallas Morning News whose ferocious anti-Kennedy fervor bled into the paper’s pages as well as in a tirade to the president’s face at a media luncheon. Of course, Kennedy would later be killed in Dealey Plaza, named for the publisher’s father.

Paced month-by-month, the authors move from Kennedy’s election toward the moment of the first shot that exploded into the presidential motorcade. As a collection of richly imagined vignettes moving against the ticking clock, "Dallas 1963" builds momentum on the borrowed suspense that comes from the reader's knowing how this book will end. Appropriately or not, a sense of inevitability foreshadows all that came before.

The authors comb through the anti-communist paranoia that reached fever pitch in a city that despised Texan Lyndon B. Johnson as a traitor. A fierce contingent of the John Birch Society took hold in Dallas during the Kennedy administration, as did an emergent National Indignation Conference (which, when it expanded countrywide, actually called itself the “National National Indignation Conference.") Jack Ruby ran a soft-core strip club that catered to the Dallas elite that had a glad-handing network of power driving the city. They saw Kennedy as – in Dealey’s words – not a “man on horseback” leading the nation but a man “riding Caroline’s tricycle.” They charged rhetoric-inflamed citizens to drop the usual politenesses and behave in a mob-like manner, as when the leading citizens of Dallas angrily swarmed Johnson and his wife in 1960. The morning of Kennedy’s assassination, the Birchers had run a mocking full-page ad in Dealey’s News, and printed “wanted for treason” fliers featuring a mock mug-shot of Kennedy.

Meanwhile, the book portrays civil rights activists, like Rhett James, and moderate business leaders, like Stanley Marcus of the Nieman Marcus department store, as heroic characters who dream of a more just and peaceful Dallas. But they are stymied by a climate of hatefulness and combat that would position Dallas, as a city, to take the blame for Kennedy’s murder – fairly or not.

It’s difficult to read "Dallas 1963" and not see uncomfortable parallels to the angry political divisions of today. With tremendously good research and graceful storytelling, the authors reveal the accelerating power of reactionary politics. Readers get close to the lives of an extraordinary cast of characters with conflicting visions for what kind of city Dallas should be. It is a meaningful, contextual story, that not only maps out the city’s connection to the president but also explores a schematic of political warfare, along with the bending relationship between city and nation. With a clean economy of language, a genius sense of detail, and a great feel for quotation, the book opens up this conflicting story to a broad swath of readers.

The authors are, however, limited by their own structure. The month-by-month vignettes are unfailingly descriptive, with more speculation then action used to give readers a peek in the minds of H.L Hunt, Stanley Marcus, and the rest. Despite the steady move toward a chilling moment, the book drags in the middle as the portraits of yet more reactionary rhetoric, hypocrisy, and good-intentioned pushback began to feel redundant. The narrative was also truncated by some characters appearing more fully developed than others. The civil rights leaders, for example, are filled with self-reflective questions. The villains of the story have no questions, only certitude about combating the Communist menace on their turf in Dallas. It gives the book a cardboard feel.

Nonetheless, "Dallas 1963" holds a wealth of riveting information and Minutaglio and Davis often make brilliant connections between the unfolding politics of nation, state, and city – and the violent stakes beneath them all.

Anna Clark is a freelance writer in Detroit.