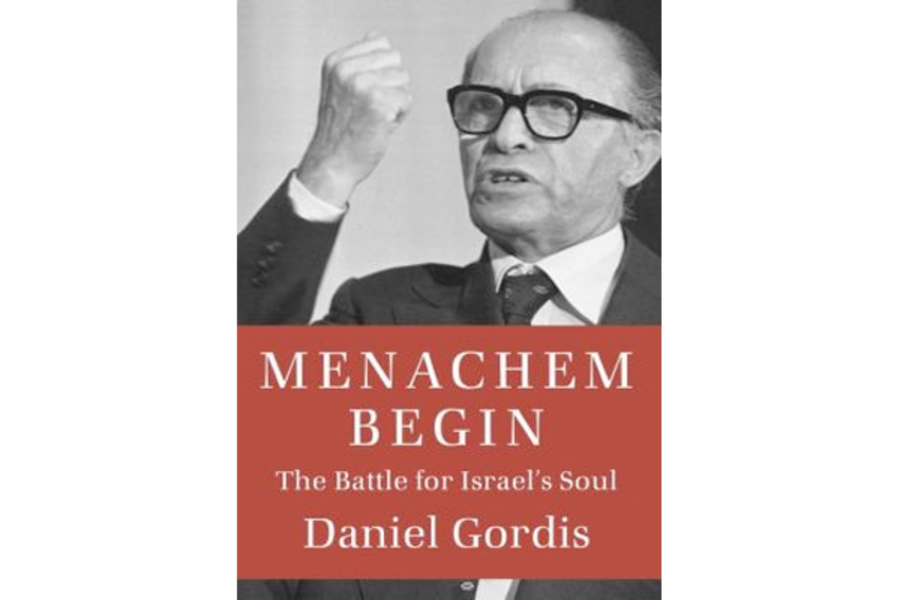

Menachem Begin: The Battle for Israel's Soul

Loading...

At what point is a people justified in using violence to carve out an independent homeland? What makes "a people"? When (if ever) do the colonized and oppressed become the colonizers and oppressors? Menachem Begin: The Battle for Israel's Soul raises all of these questions and more in pursuit of its subject, a man author Daniel Gordis describes as "the most Jewish of Israel's prime ministers."

Begin – ideologue, Zionist, revolutionary outlaw, and eventually prime minister of Israel – is a profoundly misunderstood man according to Gordis, who paints his subject as a deeply religious and essentially decent person who was depicted as an extremist and fascist even as he negotiated peace with Egyptian president Anwar Sadat and warmly welcomed to Israel refugees from Africa and Asia.

Born in Brest (now in Belarus) in 1913, Begin is an unlikely hero in some ways – an awkward bookworm who became a gifted orator and hardened fighter in pursuit of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. He was also a man whose religious devotion was such that when he went underground to evade the British in 1944, he was able to easily pass as a rabbi, dispensing Talmudic wisdom as he avoided capture.

In capturing Begin's story, Gordis also tells the history of the State of Israel. That history is a bubbling cauldron, starting with diaspora life and rampant anti-Semitism in Europe, moving on to the Holocaust, then to the often-violent campaign for an independent state, and finally to the defensive wars that preserved and expanded Israel's borders amid a sea of hostile neighbors.

Interspersed throughout are searing flashbulb incidents from Begin's life and times: Two Jewish independence fighters who killed themselves with a grenade while singing Israel's (future) national anthem rather than allowing themselves to be hanged by the British; the brutal bombing of the King David Hotel by Irgun fighters operating on Begin's orders; and the 1948 shelling of the arms-laden Irgun ship Altalena by soldiers loyal to David Ben-Gurion, which resulted in the death of 11 Jews. Begin, who had been aboard the ship, was nearly killed in the clash, which dramatized the degree to which Israel was born not of a unanimous vision, but of many often starkly contrasting ideas and organizations.

Gordis handles the violence and controversy of Begin's life with an even hand and readers are free to bring as much (or as little) ideological and philosophical baggage to the story as they wish. It's fascinating to watch how frequently Begin's role evolves, from powerless youth, to rebel, to political exile, to prime minister, and then back to political exile again.

American readers will particularly appreciate the vivid comparisons and contrasts Gordis makes between the founding of Israel and the American revolution. Both used violence to achieve independence from British control and both Palestinian Jews and American settlers clashed, sometimes viciously, with native peoples.

That said, Gordis argues that the Israelis have come out the worse for public opinion due to the freshness of the country's founding and the skillful courting of public opinion by Palestinian leaders. And while one could argue that the bombing by Jewish independence fighters of the King David Hotel has no real analogues in the American Revolution (George Washington made strenuous efforts to maintain a hold on public opinion, including treating British prisoners of war with care), the comparison is thought-provoking.

Gordis consistently credits Begin with being earnestly consistent to the point of stubbornness, as when Begin stands with the minority of Israelis who wished to reject post-war reparations from Germany on the grounds that the Jewish state would lose all respect if it took money from its former oppressor.

"During the debate [over Holocaust reparations from Germany], and afterward, Begin had emerged as the defense of the Jewish soul of the Jewish state," Gordis writes. "He was redefined as the political voice for whom the dignity of Jewish memory and its inseparability from Jewish survival mattered more than anything else. In some respects, the episode cleared the way for the role he would eventually play as the most Jewish of Israel's prime ministers."

In "Menachim Begin," Gordis manages to capture, in clean clear prose, the heart of Israel's founding and formative years: the soaring idealism and bare-knuckle pragmatism, the shows of Jewish unity and the bitter feuds, the inspiring stories of survival and the depressing anecdote of violence. It's a good place to start for the contemporary reader curious about one small but central clump of the tangled roots of the Middle East's current turmoil.

James Norton is a Monitor contributor.