Egg

Loading...

A whole book about eggs? How cracked and scrambled is that, you may well ask. As Michael Ruhlman demonstrates passionately in Egg, his latest attempt to break down the magic of cuisine into comprehensible bites, the humble yet elegant protein-packed orbs are one of the fundamental building blocks of cooking.

Never mind their various breakfast star turns – fried, poached, hard-boiled, coddled, scrambled – eggs are essential to mayonnaise, mousse, macarons, quiche, custard, and cake. Although economical, their yolks add unctuous richness to Béarnaise sauces, pastas, and buttercream icings, while their whipped whites add lightness to meringues and crystal clarity to consommés.

"Egg" includes recipes for all of these delights, but its focus, like Christopher Kimball's excellent "Cook's Illustrated" magazine and books, is more on instruction and explanation of the science of cuisine than on novel culinary concoctions. With its clear, step-by-step photographic illustrations of various preparations (by Donna Turner Ruhlman, the author's wife), "Egg" is a book that could serve as a useful primer for novices but will especially appeal to avid cooks who are curious about why and how recipes work.

For Ruhlman, who has co-authored "The French Laundry Cookbook" and "Ad Hoc at Home" with chef Thomas Keller, and written entire volumes about rendered chicken fat ("The Book of Schmaltz") and the basic proportions of everyday recipes ("Ratio"), marveling about eggs makes sense. The yolk, he writes, "is a kind of diva in the kitchen. The white is more akin to an Olympic gymnast – its range and power are nothing short of astonishing."

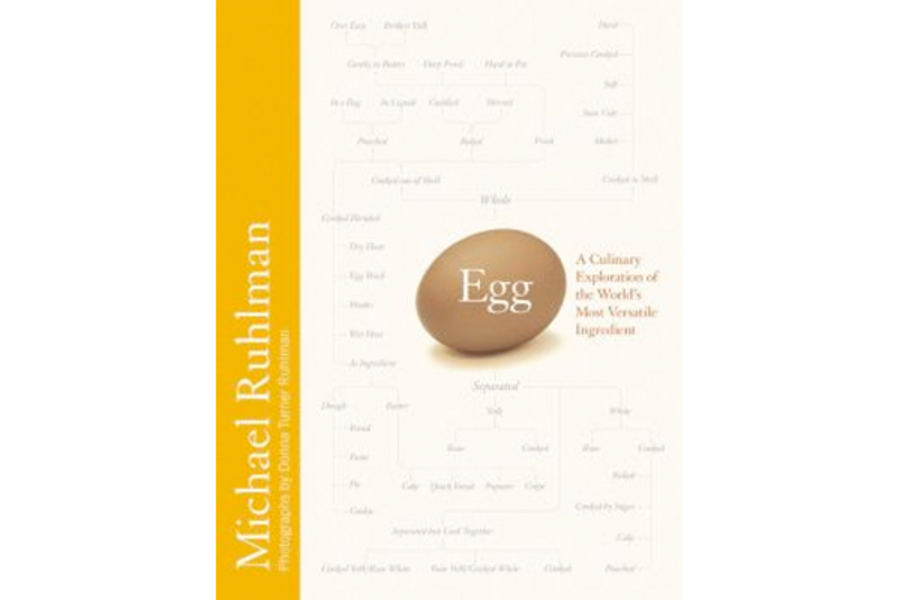

There's a lot to cover, and Ruhlman organizes it all by technique, purpose, and which part of the egg is involved – whole in the shell, whole out of the shell, separated, blended, raw, cooked, used as wash, binder, custard, enricher, garnish. To graphically demonstrate this seminal ingredient's remarkable versatility, Ruhlman has created a four-foot-long foldout flowchart of egg preparations that's equal parts brilliant and insane.

The nutritionally balanced wonder that Alton Brown calls "the Rosetta stone of the kitchen" has had some rough knocks. Wartime shortages and fear of cholesterol have led to workarounds that include eggless cakes and jarred, eggless mayonnaise. Before cracking Ruhlman's recipes, you'll want to throw cholesterol caution to the wind and recall Nora Ephron's hilarious disdain for egg white omelets: In contrast (and unlike Ruhlman), she insisted on enriching hers with extra yolks – and suggested sending the unused whites to California.

For his recipes, Ruhlman recommends super-fresh, pasture-raised large eggs, though he explains the baffling proliferation of designations, from cage-free to natural to American Humane Certified.

There's science even to the perfect hard-cooked egg, it turns out. Ruhlman's fail-proof method involves covering cold eggs in a pan with water. After bringing this to a full boil, you remove it from heat and let sit, covered, for 15 minutes. Then you remove the eggs to an ice bath to chill completely. "If you overcook them or fail to chill them quickly and thoroughly," he warns, "ferrous sulfide, with a gray-green color, the odor of sulfur, and an off flavor, can form on the surface of the yolk" – yielding what I call the Dr. Seuss green egg effect. A closeup photograph helpfully illustrates the difference between undercooked, overcooked, and just right eggs.

Ruhlman quickly builds from such fundamentals to classic dishes, including breaded chicken cutlets, crème caramel, and bread puddings. Drawing on his work for "Ratio," he reminds us that "when you remember that a custard is two parts liquid and one part egg, then you have a simple and delicious formula to use up leftover bread for either a savory dish, as with Thanksgiving dressing, or a sweet dessert." Similarly, he notes that muffin, pancake, and fritter batters share the same essential "architecture" – "equal parts flour and liquid by weight, half as much egg and butter." Add more liquid, and you end up with crepe batter.

By the time he reaches more elaborate preparations, such as Seafood Roulade, he's pretty much laid the groundwork. But he jumps jarringly to his sister-in-law's fancy Lemon Cream Cake, which involves no fewer than four separate recipes, without introducing more simple sponge cakes first. His mega-batch of brownies – which requires 8 eggs, a pound of butter, and four cups of sugar – is more my speed. And speaking of speed, using his method, I was able to whip up a delicious, glossy batch of lemony mayonnaise in minutes, as promised, through the magic of a single egg yolk emulsified in just the right amount of water, lemon juice, and vegetable oil. Miraculous.

What's next for Ruhlman? How about a book about butter?

Heller McAlpin reviews books regularly for the Monitor, NPR.org, The Washington Post, and other publications, and writes the Reading in Common column for The Barnes & Noble Review.