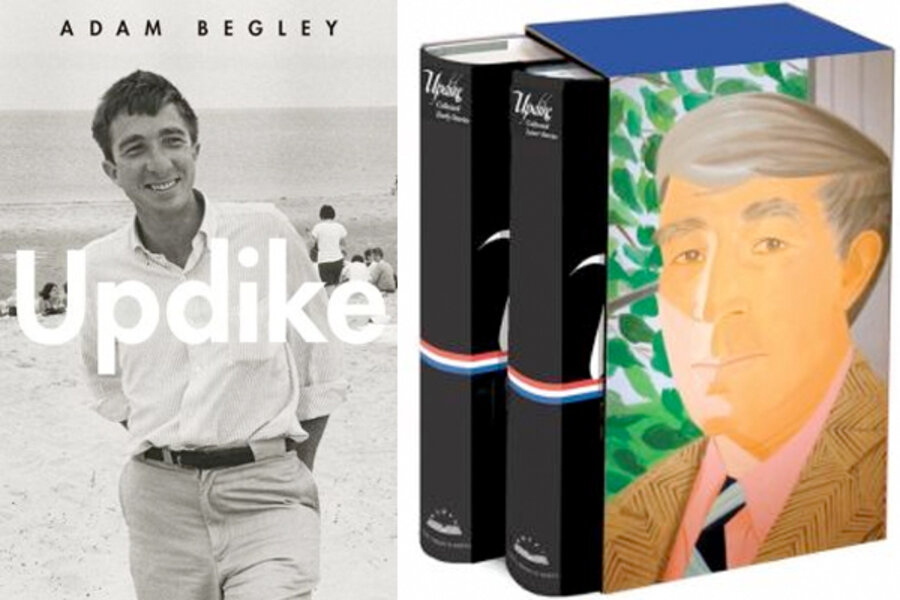

'Updike' and 'John Updike: The Collected Stories'

Loading...

Since his emergence in the 1950s as the Wunderkind from Shillington, Penn., John Updike has been an important American writer. Yet over the final decade of his life, the author’s reputation slipped slightly, with critics slamming his work as old-fashioned, misogynistic, and narcissistic.

While Updike’s legacy was beginning to decline, his death in 2009 brought new vitality to Updike Studies: multiple posthumous publications, establishment of the John Updike Society, purchase of his childhood home and its restoration as a museum, reissue and new editions of earlier volumes. Now, more significantly, comes the first major, full-length biography, as well as his collected stories in an attractive boxed set from the Library of America. Both publications signal the initial effort toward ensuring Updike’s inclusion in the American canon.

Adam Begley’s biography has been eagerly anticipated, in part because Updike was “repulsed” by the idea of someone, other than himself, writing his life story, but also because of questions as to whether his literary estate and family would cooperate. It appears they mostly have. Begley, the former books editor for the New York Observer, has composed an insightful, compelling, discreet, and admirable biography. While Updike’s marital infidelities are addressed, Begley discloses few names. Some readers may wish for more details and blood, yet there is surely a difference in how candid a tactful biographer can be about his subject five years – versus, say, a century – after the author’s death.

Begley begins with a wonderful anecdote that sheds light on Updike’s literary method. In 1983, a freelance journalist, William Ecenbarger, is granted an interview with Updike, conducted during an automobile ride near the author’s mother’s home. Ecenbarger’s piece appears in the Philadelphia Enquirer. A few weeks later comes a surprise: the New Yorker publishes an Updike short story, “One More Interview," depicting an actor who reluctantly agrees to drive around his hometown with a journalist. Ecenbarger, writes Begley, “was astonished.... Updike had transcribed, verbatim, their exchanges." The episode reveals the degree to which Updike’s writing emerged from his daily life. As Updike once explained, “Creative excitement has invariably and only come to me when I felt I was transferring, with a lively accuracy, some piece of experienced reality to the printed page."

Over the ensuing 500 pages, Begley documents Updike’s life which, except for adulterous liaisons, is largely spent reading and writing. An only child, Updike is born in 1932 to a Depression-era family in a small Pennsylvania town. Shaped for greatness by his strong-willed mother, Linda, herself an aspiring writer, the gifted student leaves Pennsylvania, earning a scholarship to Harvard, where he meets and marries his first wife, Mary.

He soon lands a job at the New Yorker, and prolific literary success follows. Married with children, the Updikes exit New York City in 1957 for small-town life in Ipswich, Massachusetts, where he writes "Rabbit, Run," "Pigeon Feathers," and "The Centaur." Now a New Englander, Updike turns from writing about a Pennsylvania boyhood to young domestic life and adultery, publishing "Couples" and "Marry Me."

Following a series of affairs that threaten his marriage, he and Mary divorce in 1974. In 1976 he marries Martha Bernhard, with whom he spends the rest of his life. With a burst of vitality, he publishes some of his finest fiction in the late 1970s and early 1980s – "The Coup," "Too Far to Go," "Rabbit Is Rich" – and emerges, through his book reviews and essays, as America’s foremost “man of letters.” Retreating with Martha to a bucolic white mansion on the North Shore of Massachusetts, the child of humble means lives a more secluded, privileged existence. His "Rabbit" novels and collected short stories are increasingly viewed as his most significant work.

The books of his final 15 years garner less attention. He dies in 2009.

Begley’s biography is admiring and affectionate toward his subject, yet he does not let Updike completely off the hook. We experience the painful process, stretching from 1962 until 1974, during which Updike tried to leave his first wife and four children. In the fall of 1962, Updike is threatened with litigation by his lover’s husband, which leads the Updikes to accept “banishment” to Europe for two months. Throughout this period, Updike is churning out short stories about adultery, painful loss, and longing, again revealing the extent to which his writing drew on the personal. Yet turning an interview into a New Yorker story is one thing; using one’s children, as he does years later, as “fodder for the fictional record of their parents’ failing marriage” is quite another.

As his eldest son David acknowledged, his father “decided at an early age that his writing had to take precedence over his relations with real people." Begley, however, doesn’t render judgment, but rather leaves it to the reader: Was Updike exploiting those around him, or was his truthful witness of those lives something altogether different?

In synthesizing a substantial amount of material (Updike published more than 60 books) through clear, intelligent prose, Begley does what I never thought possible: he writes a biography I wished were longer. He adeptly handles the arc of the larger life while sprinkling an array of engaging facts, some of which I hadn’t before known – e.g., Updike briefly considered being a math major at Harvard, his first two novels were actually rejected by his publisher, and he painted the exterior of his house while composing "The Coup."

That said, the biography is not without flaws. Begley’s analysis of Updike’s writings, though sensible, is also conventional and, stretching for a page or two at a time, can be tedious. There are also phrasings which feel odd, such as “adulterous high jinks,” “adulterous shenanigans,” and Updike’s “adoration of pretty young things." Yet these are minor quibbles. Begley succeeds in delivering a sympathetic portrait of a gifted writer who, through tremendous energy and ambition, realized a major career by harvesting the mundane events of his life.

The publication by the Library of America of 186 of Updike’s more than 225 short stories (the unincluded Bech and Maples stories will appear in future LOA collections) will not register as much attention as the biography, particularly since these stories have already appeared in earlier collections. Yet it is likely, decades from now, that these two volumes of chronologically arranged stories will prove an even more precious, sustainable resource than any biography. Think of how many biographies of Hemingway have appeared, then consider how much more valuable his actual stories are.

For Updike, too, the stories may ultimately be the strongest work, largely because his method of rendering the texture of a particular moment may be better suited to the short story form. It is also the stories (“Pigeon Feathers,” “Separating,” “A Sandstone Farmhouse”), rather than the novels, that reveal Updike at his most autobiographical, which again suggests why they may stand as a better and more intimate depiction of the author’s life than a biography.

What is particularly noteworthy about the LOA edition is that the stories are in their final form, as determined by Updike in 2004, and that editor Christopher Carduff provides useful notes on each as well as the most comprehensive author chronology to date. Carduff has performed the editing work on the bulk of Updike’s posthumous writings, and he has, again, done a masterful job, revealing himself as a wise, judicious editor who, like great athletes, makes it look easy.

More than any of his literary peers or forebears, Updike paid careful attention to and celebrated the experiences of quotidian existence, and through the fine work of Begley and Carduff, important early groundwork is being done to confirm Updike’s place in American literature.

James Schiff teaches at the University of Cincinnati and has published several books on contemporary American fiction.