A Window on Eternity

Loading...

At the bottom of my living room bookshelf, where I keep all the books too big to fit anywhere else, I have a copy of “A Gap in Nature,” a beautiful 2001 volume by Tim Flannery with gorgeous illustrations by Peter Schouten. Except for the oversized Audubon prints that have colonized my coffee table, I can’t think of a more beautiful book in my home library than the one that Flannery and Schouten produced.

But “A Gap in Nature” rarely leaves the shelf, for the simple reason that it documents a reality too stark for me to easily confront. In page after page, in exquisite portraits, Schouten depicts a range of species, from the dodo to the Carolina parakeet, that have been rendered extinct.

I mention this to suggest the way in which most trade books about modern ecology, no matter how well-executed, can quickly become an exercise in dread. Given the implications of pollution, global warming and the shrinking rainforest, even an expertly rendered account of today’s environment tends to carry news too heavy to bear.

That’s why A Window on Eternity, the latest book from Edward O. Wilson, is an especially welcome event as another spring arrives. In this season of renewal, Wilson suggests that our tired planet, managed wisely, can still demonstrate an enormous capacity for regeneration.

Wilson tells the story of Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique, which boasts one of the densest wildlife populations in Africa. During a civil war that lasted from 1978 to 1992, much of the park ecosystem was destroyed, and its future seemed bleak. Some animal populations within the park declined by 90 percent or more.

But then a wealthy American entrepreneur, Gregory C. Carr, launched an audacious effort to bring the park back to life. Slowly, the park is returning to its original state.

Wilson, an entomologist who specializes in ants, has written many acclaimed books that attempt to explain ecological concerns to a popular audience. In “A Window on Eternity,” as in most of his other works, Wilson uses his study of ants to explain larger subjects. Like William Blake, who saw eternity in a grain of sand, Wilson finds much to learn from such tiny creatures as Matabele ants, driver ants, and termites. Exploring their complicated hierarchies like a society columnist reporting from Park Avenue, Wilson suggests that the complicated equilibrium among ants is part of the broader and equally delicate ecological balance that touches all earthly life, including humans.

“Anywhere I am in the world I love it when the air is warm and moist and heat bounces off the sunlit earth, and insects swarm in the air and alight on flowers and come in droves to lights at night,” Wilson tells readers. “I remind myself that their species number in the hundreds or thousands. None to me is a bug. Each instead is a kind of insect, the legatee of an ancient history adapted to the natural world in its own special way. I wish I had a hundred lifetimes to study them all.”

Such lyrical passages underscore Wilson’s enduring debt to Henri Fabre, the French entomologist and writer who always had his nose to the ground, with magnifying glass in hand but his head firmly planted in the cosmos, contemplating the big questions of existence.

As the title of “A Window on Eternity” suggests, Wilson has his eye on the longer view. Aside from the immortality promised by religion, Wilson argues, humans should also value and nurture the continuity of life on Earth. He uses Gorongosa as a way to consider how such stewardship might be applied on a global scale.

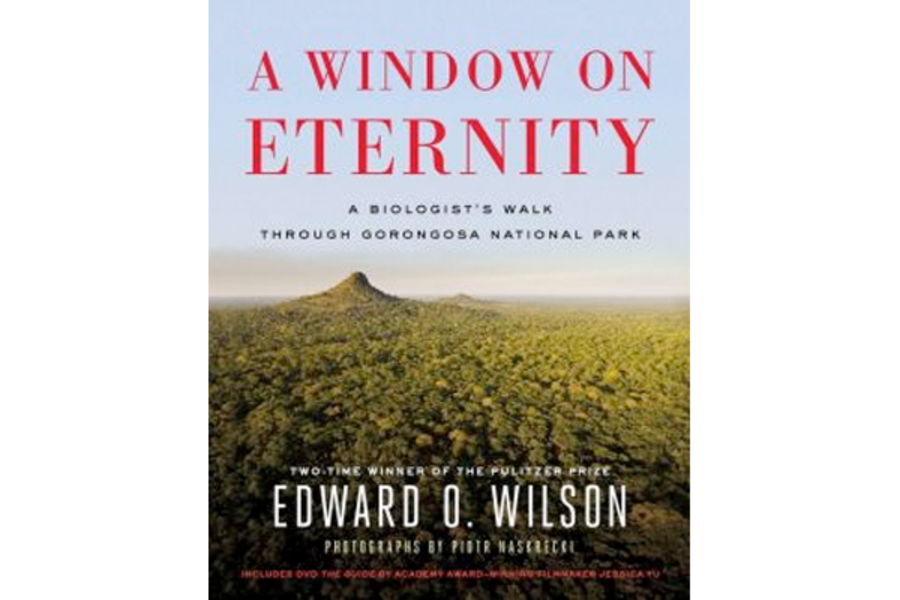

Wilson’s prose consistently strikes a note of transcendence, and one sees a hint of that, too, in the pictures of Gorongosa by Piotr Nasrecki that accompany the text. In an opening composition, a tiny campfire throws its light against the enormity of the star-studded African sky, a nice complement to Wilson’s musings on the smallness of man in the cosmic scheme of things. Nasrecki proves equally attentive within the tiny landscapes of Wilson’s bug world. In one photograph, a black and yellow tarantula rests on its web, the spider’s surface as finely detailed as a designer brooch.

The ambition of Nasrecki’s art sometimes seems constrained by the book’s modest format. “Lavish” is an adjective commonly assigned to picture books, but “A Window on Eternity” doesn’t aspire to architectural heft or opulence. It’s slightly bigger than an issue of National Geographic; in fact, “A Window on Eternity” sometimes comes across as a magazine article that’s been huffed and puffed into a book.

And like any piece of journalism, Wilson’s book has the feel of a story in which the ultimate ending remains unclear. Whether the success of Gorongosa can be multiplied across the planet is very much an open question. But Wilson is crossing his fingers.

“While our species continues to manufacture its radically different and untested all-human world, the rest of life should be allowed to endure, for our own safety,” Wilson writes. “While preserving our own deep history, it will, if we choose to let it, continue on its own trajectory through evolutionary time.”

Danny Heitman, a columnist for The Advocate newspaper in Louisiana, is the author of “A Summer of Birds: John James Audubon at Oakley House.”