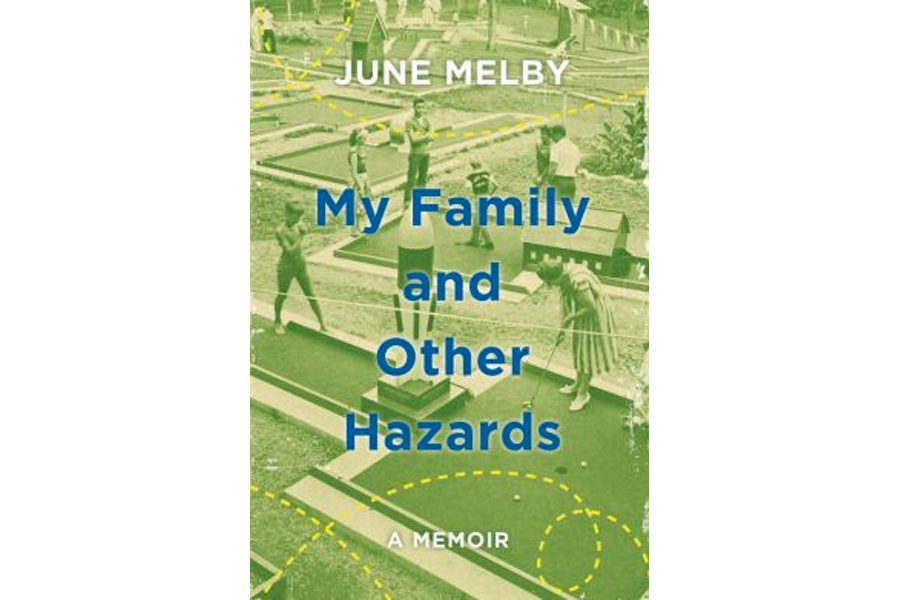

'My Family and Other Hazards' is a wonderful, witty account of growing up on a mini-golf course

Loading...

For its many devoted practitioners, the words “miniature golf” have a warm, familiar ring. Perhaps that is why the sport is as synonymous with summertime as swimming pools or backyard stargazing. Perhaps that is also why, when writer June Melby tells strangers that she spent the better part of her childhood living adjacent to a miniature golf course, the first question she is typically asked is not one of shock or surprise.

With rare exception, Melby writes in her new memoir My Family and Other Hazards, inquiring minds want to know whether or not the course included a windmill. Melby just can’t get over it: “That’s your first question? I think. About growing up on a mini golf course? About having tourists in your backyard?” For the record, Tom Thumb Miniature Golf in Waupaca, Wis. – purchased by the author’s parents, George and Jean, in 1973 and operated by the family during summers for the next 30 years – did have a windmill, but the book doesn’t dwell on that fact. There are far more interesting questions to ponder.

One that is never fully answered is what inspired two buttoned-down schoolteachers to enter the uncharted territory of putters, golf balls, and “hazards,” also known as obstacles. As the book begins, George sits down his three daughters (LeAnn is the eldest, Carla the youngest, with June in the middle) and asks them a question that is as bewildering to us as it must have been to them: “What would you think if our family bought Tom Thumb Mini Golf Course?” Before they can answer – no pressure, of course – Jean pipes in: “So, girls, would you like that?” Without knowing what they are in for, the trio answers in the affirmative. But the undertaking proves to be so all-consuming, Melby writes, that she came to no longer associate her pre-Tom Thumb life – those halcyon days when her family was “innocent and church-going and living peacefully in a small town in Iowa” – with her childhood at all.

Unacquainted with physical labor, Melby (who was then 10) and her sisters appeal to their status as juveniles order to get out of the drudgery involved in caring for the grounds and handling the clientele. “Like most children,” Melby writes, “we are accustomed to estimating how much work can be expected from us ‘at our age’ before we can complain and disappear without a chase.” George and Jean are unmoved, doling out spiral notebooks that are little more than child-sized time sheets. “You can use these to keep track of your work,” Jean says. “What jobs you do, what time you start and stop.” Their pay, tabulated on a sliding scale according to each child’s age, ranged from 35 to 75 cents an hour. For customers, prices are kept low in a kind of observance of the Golden Rule. As Jean says, “We’re going to charge what we would want to pay for our family if we were on vacation.”

Perhaps the Melbys took over Tom Thumb to instill the very real virtues of thriftiness and industriousness in their offspring. The sisters eventually accept their various responsibilities, perhaps inspired by the example of their mother. Whether scraping the insides of a cotton-candy maker or cleaning the course’s pools, Jean goes about her duties uncomplainingly, a trait which must have run in the family. Her father – the author’s grandfather – is remembered for having refused a slice of cake following a hearty dinner: “I’ll rather have more corn. Corn will be my dessert.” The book is, among other things, an appreciative nod to Midwestern stoicism.

Each of the book’s 18 chapters (tied to the course’s 18 hazards) is accompanied by an appropriate, if sometimes allusive, epigraph, such as this one by Dorothy Parker: “I don’t know much about being a millionaire, but I’ll bet I’d be a darling at it.” Armed with a droll, understated voice that recalls Parker, Melby is at her funniest when recounting the visitors who make the trek to Tom Thumb – the “syrup-filled kids” who pour out of a Lincoln Continental or a gaggle of campers who arrive in a fleet of 40 canoes. “For reasons we could never explain,” she writes, “customers arrived in clumps, three cars at a time, four at a time, unrelated families and unsuspecting couples, all pulled in at the exact same moment.” Melby has a vivid descriptive style, probably aided by her stand-up comedy background, as when the smell of a lake is likened to both “the inside of a greenhouse” and “the inside of a moldy shower stall.”

Yet the experience ends up as a study in sociology for the brood. From tourists to bikers, the Melbys encounter a wide swath of humanity. They coin nicknames for regulars – e.g., “The Victorian Ladies,” “The Sit-Down People” – though, to his daughter’s eternal irritation, George’s favorite customers are salt-of-the-earth types. “When a man wore a mesh farmer’s hat, my dad perked up like a talk show host,” she writes. The book is packed with self-contained vignettes that have the shapeliness of a well-told joke – such as the episode in which a series of increasingly specific signs are required to discourage drinking on the premises (advancing from “NO BEER ALLOWED ON THIS COURSE” to “NO ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES ALLOWED ON THIS COURSE”). When golfers are not buying enough popcorn, the children are advised to start munching on batches themselves in plain sight, the thinking being that “popcorn is contagious” and sales will pick up.

Melby includes various tongue-in-cheek how-tos – we learn all about making snow cones and cotton candy – to punctuate this wonderful, witty account of her formative years spent on the fairway. It turns out that her sentimental journey is like that of many others. “Everyone,” she writes, “feels attached to the house where they grew up.”

Peter Tonguette’s criticism has appeared in The Wall Street Journal, The Weekly Standard, National Review, and many other publications.