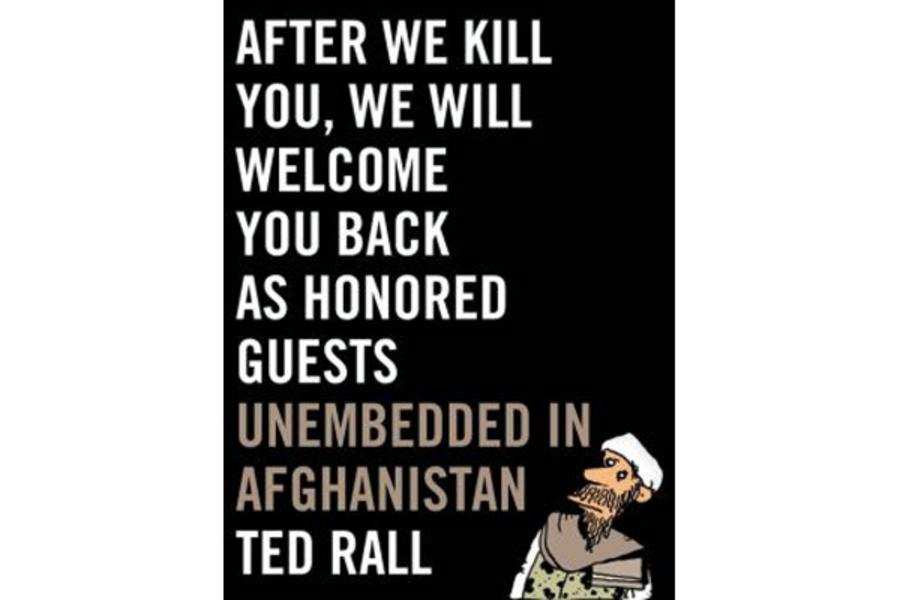

'After We Kill You, We Will Welcome You Back as Honored Guests' offers an unvarnished but informed view of life on the ground in Afghanistan

Loading...

What do Afghanistan and Charlie Brown have in common? Somebody is always picking on them. Charlie had Lucy, and Afghanistan had everybody else. Invasion after invasion: 1219, 1370, 1526, 1713, 1738, 1837, 1842, 1879, 1919, 1979, 2001– and the Afghans didn’t start one of them; they had enough on their hands with the local turf wars that flared up every few weeks. Wars are the abiding nature of Afghanistan: they don’t end, they just fade away, then return, like malaria. Genghis Khan came through and laid waste, so too Tamerlane, Babur, Gurgis Khan; Great Britain wanted a buffer state (the First Anglo-Afghan War, the Second Anglo-Afghan War, the Third Anglo-Afghan War – that, friends, is tenacity), the Soviet Union wanted a warm water port via Afghanistan to Karachi, Pakistan, and the United States wanted… what? Good question, one that journalist/cartoonist Ted Rall seeks to answer in his both mordant and discerning – as good a combination as time and money – After We Kill You, We Will Welcome You Back as Honored Guests: Unembedded in Afghanistan.

Rall slipped into Afghanistan once before, at the very start of the American invasion in 2001, via Tajikistan. He did the same this time, having cobbled together a pitiful bankroll, with two journalist/cartoonist friends. An independent spirit, he had no intention of being embedded with American troops. He wanted to be on the ground, using his wits and contacts, filing distilled dispatches from the rough, along with his cartoons – crude as a blunt pencil, his very own ontological-hysteric theater – recounting the day’s events (he had a finicky scanner, unfortunately, not a trusty carrier pigeon). He knew that to be embedded was a crippling metaphorical act, to be in bed with the military, subject to military censorship. “Our job is to win the war,” said a Marine colonel in 2003. “Part of that is information warfare. So we are going to attempt to dominate the information environment.”

Rall is a reporter you can trust. If you know anything about Afghanistan and American foreign policy, what he writes and cartoons chimes with your familiarity and experience. (Which begs the question, if other reporters get so much wrong in places we know about, what are we supposed to believe in reports for places outside our knowledge?) He plays hard; he gets dirty. He finds himself in precarious situations. He never gets bored, because the path hasn’t been swept for him, as it has the drop-in reporters looking like they just got out of bed. Rall may not be an Old Afghan Hand, but he knows how to use a squat toilet. (Toilet paper? What toilet paper?) He will tell the story as he sees it, informed by what he knows of history. “Reporters should strive for the impossible: objectivity.” At least an independent correspondent has a shot at unvarnished impressions, formed in his mind’s eye.

As Rall sees it, there is a new military paradigm – you can almost hear the policy wonks squeal with delight – at work, and has been for a little while, one that operates on the principle of occupation without annexation. It doesn’t work. It hasn’t worked from Korea to the Gulf War. Afghanistan is a textbook case. They set up a puppet government headed by a man with no local support; they fail to restore law and order; hearts and minds were won nowhere but at Blackwater and Halliburton (Dick Cheney, former chairman and CEO); infrastructure is left in ruins; ten year olds play with AK-47s, occasionally killing the odd passerby. Why don’t these kids get balls to play with, or marbles? Because marbles are in short supply, such is their demand for suicide vests.

But just because we aren’t “annexing” these lands doesn’t mean we save lots of money, notes Rall. “We spend 54 percent of the federal budget on “defense.” What we have here, writes Rall, is the “politics of disruption” – as in disrupting potentially emerging regional rivals – "the core of an aggressive form of neocolonialism, the quest not for old-fashioned empire but postmodern open markets ripe for exploitation by international corporations.” As newly discovered deposits, “including huge veins of iron, copper, cobalt, gold and critical industrial metals like lithium,” are revealed, suddenly China and Russia – suffering from early onset Alzheimer’s – are showing interest.

Meanwhile, there is 100% unemployment, a purely feudal way of life, and civil war looms as the Pashtun south eyes the Tajik-Hazara-Uzbek north. Rall searches in vain for a much-ballyhooed pipeline running through Afghanistan’s western border. It is nowhere to be seen, the start-up millions having been spent on bespoke haberdashery, prime real estate, and bigger safe-deposit boxes in Zurich. Rall – who will remind you as someone bylining Ramparts or the old Village Voice – travels to the little-visited, wickedly dangerous western regions and finds the same sentiments as in the east, and north, and south: The United States ravaged the country without cause, imposed a cruel and deadly occupation, installed a craven, depraved puppet regime (headed by a crony of G. W. Bush’s Texas oil crowd), built little, played footsy with the warlords, let the Taliban get on with it, and – same as it ever was – waved goodbye.

Of course, some of the impetus of the book is a point of view that doesn’t require on the ground reporting from Kabul: “None of the major figures linked to 9/11– including Osama bin Laden – were in Afghanistan on 9/11. (Bin Laden was in a Pakistani military hospital in Islamabad.) By 9/11, both Al Qaeda training camps in Afghanistan had been closed. Al Qaeda’s operations were based entirely in Pakistan. Afghanistan had nothing to do with 9/11. Nothing.”

“Take Afghanistan. Please.” Henny Youngman would have got a laugh. “We are an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality.” That’s Karl Rove – who never got a laugh – as he tucked a fretful nation into bed, there to ponder how a nightmare becomes reality.