'Ostend' evokes Belgium in the summer of 1936, as Europe stood on the brink

Loading...

In the Belgian beach resort of Ostend, on a side street perpendicular to the sea, there stands a small thin townhouse. Inside, you'll find long-nosed Carnival masks leering down at you from the walls, dusty shells and starfish, a painting of a death-procession, strange skeletons and odd hats. This uncanny house, once owned by the Belgian Expressionist painter James Ensor, is now a museum, but it hasn't changed much since the summer of 1936, when writer Stefan Zweig, an Austrian Jew in exile, wandered over its threshold. He gazed with disquiet at this place of decay lurking in the midst of a peaceful seaside idyll, which was supposed to shelter him from the horrors creeping over his continent.

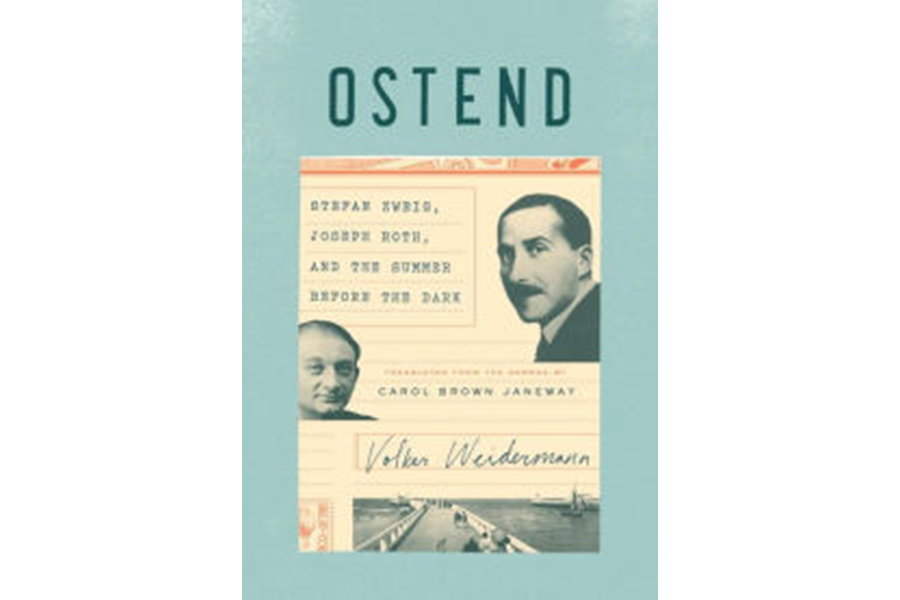

This juxtaposition of the pastoral with the subtly horrible colors many sections of Ostend: Stefan Zweig, Joseph Roth, and the Summer Before the Dark, by Der Spiegel critic Volker Weidermann. The book, originally published in Germany in 2014 and available in English this January, is a gentle narrative undercut with a sinister knowledge of impending doom.

In "Ostend," Weidermann touches on the historical events galvanizing Europe that summer, such as the infamous Berlin Olympics and the beginning of the Spanish Civil War. But the book mainly focuses on its characters, especially the friendship between Joseph Roth, a celebrated writer who transcended his roots as a poor Jewish boy from the eastern reaches of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and Zweig, also Jewish, but raised in genteel Vienna.

These two men are in exile from their beloved homeland due to the increasing power of fascism, the banning of their books in Nazi Germany, and the impending war. In "Ostend," Roth and Zweig, whose friendship is characterized by both admiration and resentment, encounter a series of other authors and cultural figures displaced by the intellectual unrest that preceded the carnage of World War II.

Roth and Zweig meet figures such as Irmgard Keun, a German writer whose books have been banned because they are considered too licentious and modern; Lotte Altmann, a student who becomes Zweig's secretary and lover; Hermann Kesten, a dramatist; and Otto Katz, a communist. These men and women write, drink, bask in Ostend's cafe culture and its seaside charm, worry about their declining careers in the face of bans in Germany, and nervously ponder Europe's fate.

Zweig works on his book The Buried Candelabrum, a tale of a Jewish treasure stolen repeatedly throughout the centuries. Roth's alcoholism worsens as he drinks himself into a stupor every night and dreams of his beloved Hapsburg monarchy returning.

Just as Roth idealized the lost Hapsburg monarchy, romantically inclined modern readers tend to idealize stories of writers, Communists, and larger-than-life cultural figures drinking and adventuring in Europe in the first half of the 20th century. The kinds of readers who loved "A Moveable Feast" or Christopher Isherwood's "Berlin Stories" will find much to like in "Ostend."

Similarly, anyone who enjoyed "1913: The Year Before the Storm," by Florian Illies, will certainly enjoy Weidermann's new book. Like Illies, Weidermann eschews heavy academic analysis, instead using a fiction writer's tricks to illuminate this historical moment. He presents Ostend as a series of vignettes, describing his characters, their backstories, their motivations and appearances, their relationships and woes, and eventually their fates.

And their fates are predictably tragic. Some of the historical figures in Weidermann's book survived until old age, but Friedl Roth, Joseph's wife, was murdered by Nazis in 1940, many of the communists were killed during World War II or during purges afterwards, and others who survived the Nazis and communists ultimately took their own lives.

Roth and Zweig never saw each other again after 1938; Roth soon had a nervous breakdown and died, while Zweig and Lotte Altmann committed suicide in Brazil during the war because they wanted to exit the world maintaining some belief in freedom, intellect, and beauty. The fate of Ostend itself was also tragic: Nazis occupied the city in 1940, and the Allies bombed it to the ground in 1944.

One of the most startling images in Ostend concerns one of the emigres, playwright Ernst Toller, who always carries a length of rope in his suitcase so that he'll have an escape route from the darkening world. Weidermann tells us that in Europe 1936, there was a metaphorical length of rope in the suitcase, but no one talked about it. Perhaps that length of rope lies at the heart of Weidermann's book, along with the enduring house of masks and death-paintings on an Ostend side street. Ultimately, "Ostend" is a melancholy evocation of a group of people and an era on the verge of being swept away forever.