'For White Folks Who Teach in the Hood' offers advice from a transformational educator

If there’s one book you read as you – or your kids – head back to school this September, make it Christopher Emdin’s.

For White Folks Who Teach in the ’Hood is really for everybody. The book, which came out earlier this year, both explains and transcends the role of race as it gets to the heart of how people sometimes unwittingly perpetuate inequities in our society.

Emdin calls out the “pedagogy of poverty” that “rewards [students] for being docile and punishes them for being overly vocal or expressive.” It’s not just the stresses of their lives outside of school, but traditional school practices as well that often disempower students from struggling neighborhoods, his research has found.

Take, for example, when Emdin was in the 10th grade and a door slammed. He hit the floor under his desk – and his teacher sent him to the principal’s office. What the teacher didn’t know: There had been a shooting outside his apartment. Emdin’s dive for cover was instinct.

Emdin, now a Columbia University professor and associate director of the Institute for Urban and Minority Education, has gone from frustrated student to transformational educator. Compelling scenes from classrooms where teachers have caught his vision inspire hope for more humane educational landscapes – in contrast to the spaces that, for too many kids, look and feel eerily similar to prisons.

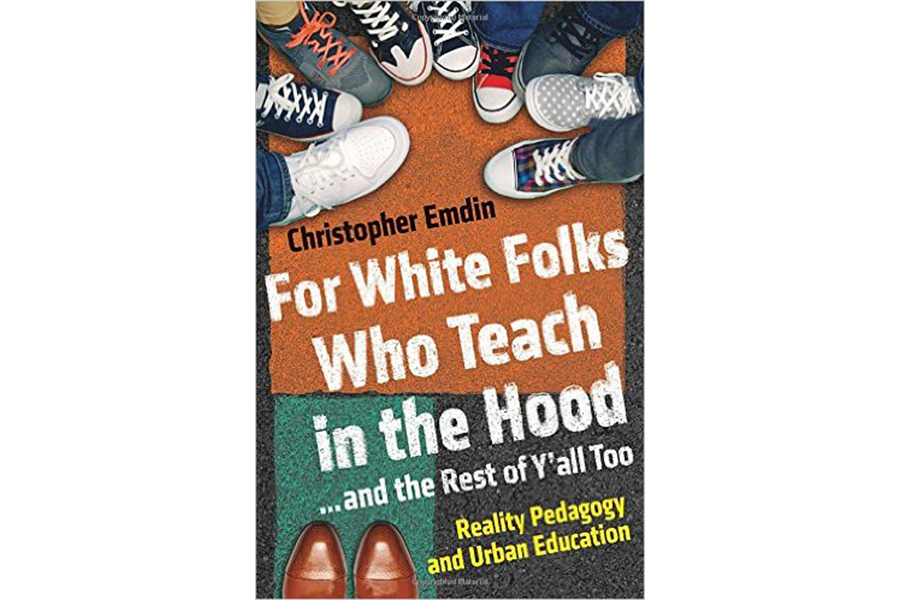

Emdin’s “reality pedagogy” shows teachers how to truly respect their students by getting to know their communities and cultures, and literally walking in their expensive, fashionable footwear.

He shows how he learned to flip the traditional rules of urban education, allowing students to express themselves, shape the class, and even co-teach it. Some of his own best ways of explaining scientific concepts have come directly from his students teaching their peers.

The book beautifully plumbs the deep streams of caring, respect, and brilliance that burst out of young people when teachers engage with them authentically – like the young woman who opted out of a much-anticipated trip to Disney World with her dad, whom she hadn’t seen in years, because she didn’t want to skip her Friday responsibility to distribute lab equipment in Emdin’s class. Surprised, Emdin checked with the student and her mother about whether something negative had happened to affect the trip. Genuinely committed to her Friday job in class, the girl had asked her dad to change her flight to Saturday. When that proved impossible, she told him she'd rather keep her class commitment – a reflection of how "emotionally connected" Emdin's students had become to his class.

As the founder of the social media movement #HipHopEd, Emdin’s turned youths’ love of rap into teaching tools that go far beyond assignments to write songs about equations or blood cells. He draws on all sorts of urban forms of expression – the call and response of preachers, graffiti art, special handshakes – to create a sense of family and to position “academic achievement as a shared-classroom family goal.”

It boils down to asking adults to make way for students’ own drive to understand the world and take on roles as leaders.