'Moonglow' is a magic family epic, told with magnificent disregard for the facts

Loading...

Michael Chabon and Ann Patchett are both writers steeped in imagination, who usually range far afield for inspiration – from Prague magicians turned comic book artists to opera singers being held hostage in Latin America. This year both have stuck closer to home, but the results are just as memorable.

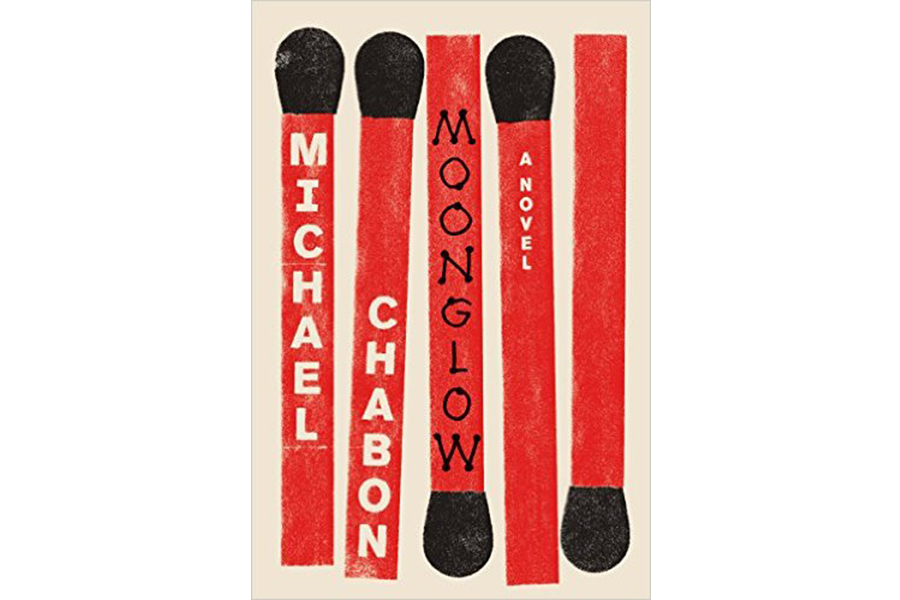

Patchett’s “Commonwealth” follows a group of stepsiblings who were thrown together during summer vacations as they forge a new sense of family, in a way that will feel familiar to readers of her nonfiction essays. Chabon, for his part, blurs family history and fiction in his captivating new novel, Moonglow.

“In preparing this memoir, I have stuck to facts except when facts refused to conform with memory, narrative purpose, or the truth as I prefer to understand it,” the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of “The Adventures of Kavalier and Clay” writes in an author’s note. “Wherever liberties have been taken … the reader is assured that they have been taken with due abandon.”

The narrative is a swirl of family stories, mostly starring his grandfather: the time his grandfather went hunting a cat-eating python in the Everglades with a snake hammer instead of a gun; the time he tried to strangle his boss with a telephone cord; the time he went to prison and accidentally created a bomb; the time he went hunting the Nazi scientist Wernher von Braun and his fabled rocket.

“Ninety percent of everything he ever told me about his life, I heard during its final ten days,” Chabon writes of his grandfather, a pool hustler, engineer, and maker of meticulous models for NASA whose early years as a piano mover quite literally made him larger than life. The chapters set in World War II form the heart of the novel as the skystruck young member of the Army Corps of Engineers gradually realizes his hero, von Braun, is complicit in heinous crimes against humanity.

Chabon presents himself as the family stenographer, bringing his grandfather cups of tea and then fading into the background as another story unfolds. “Moonglow” may be less showy than some of his earlier works, but Chabon manages to pull off a disappearing act while laying bare generations of secrets – not a feat for an amateur. He also presents it as a radical departure from the family credo of silence. “Keeping secrets was the family business,” Chabon writes, “but it was a business that none of us ever profited from.”

“What’s the point of talking about it?” his mother says about one horrifying betrayal. “Everybody already knows.”

Before Chabon, the family storyteller was his grandmother, an actress and Holocaust survivor who was tormented by a past about which she may not have been forthcoming. While babysitting, she would read her grandson tarot cards or tell him fairy tales that would have terrified the Grimm brothers. Her husband could repair all kinds of machines, but humans are harder. Protecting and caring for his wife and her young daughter became his mission in life – one that took all his considerable resources and then some.

Realizing it can’t be done on earth, he builds a model moon garden and puts figures of the three of them in it – creating a utopian Moon city where she could live in peace, at least in imagination. “The thing that made space flight difficult was the thing that, to my grandfather made it beautiful: To reach escape velocity, my grandmother, like any spacefarer, would be obliged to leave almost everything behind her.”

While his grandfather maintains there is no point in trying to explain a life, his grandson counters that the inquiry is the point.

“ 'Anyway, it’s a pretty good story,' I said. 'You have to admit.' ”

“You can have it. I’m giving it to you. After I’m gone, write it down,” says his grandfather, who regarded novels besides “The Magic Mountain” and certain hard science fiction as “baloney.” “Explain everything. Make it mean something. Use a lot of those fancy metaphors of yours. Put the whole thing in proper chronological order, not like this mishmash I’m making you.”

Chabon doesn’t worry too much about chronology or fancy metaphors, but the “mishmash” of “Moonglow” is definitely rich with meaning.