'Victoria the Queen' is a cheerful, chatty success from start to finish

Loading...

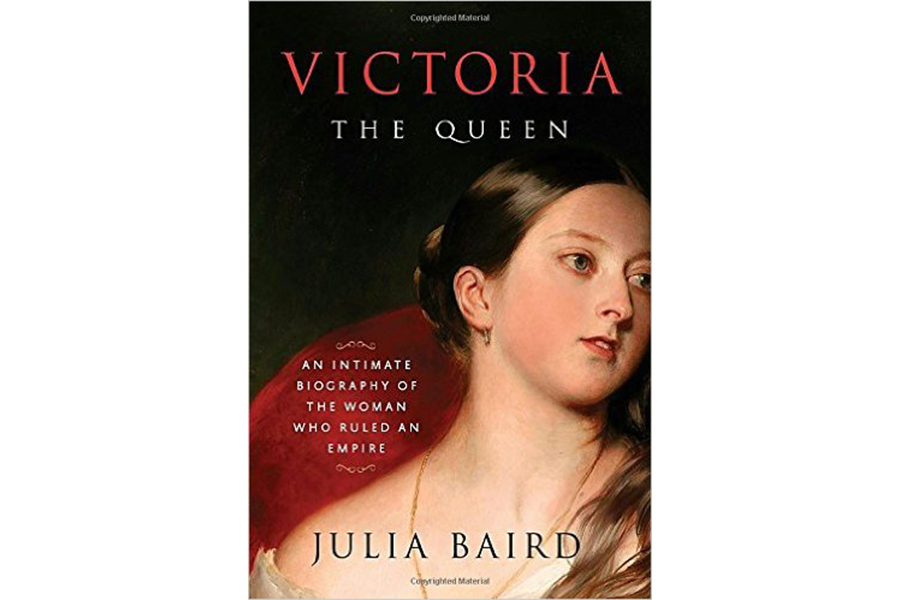

Journalist and columnist Julia Baird's new book Victoria the Queen: An Intimate Biography of the Woman Who Ruled an Empire, is an inviting thing, sumptuously produced by Random House and adorned with a fetching portrait-detail of the young queen done by Franz Winterhalter. Its subtitle promises the prose equivalent of the cinematic payoff viewers have been enjoying with ITV's lavish TV series starring Jenna Coleman: a look behind the forbidding Victorian facade. It's a promise writers have been making about this particular monarch for well over a century.

Long before Victoria died in January of 1901, she'd been the subject of biographies both good and otherwise, and the floodgates were flung wide upon the publication of Lytton Strachey's slim, slightly but nonetheless scandalously snide life in 1921. Since then, there have been dozens of biographies, each struggling in its own way to grapple with the vast length of the subject's life.

Victoria was born in 1819 and reigned for 63 years; she was Empress of India and mother to an entire generation of European royalty; by sheer force of personality she impressed her name on an age but remained very self-consciously remote for more than half her long time on the throne. She was both highly opinionated about the workings of the governments that acted in her name and almost entirely powerless to affect those workings in any concrete way.

In the informal concepts that have attached to royalty since her own day, the Crown could question, quibble, and occasionally quarrel, but statesmen and parliamentarians only deferred to her – and continue to defer to her successors – out of an ironclad sense of tradition. It's an incredible combination of power and impotence, and for well over a century it's presented biographers with some daunting challenges, the main one being the contrast between the vivid colors of Queen Victoria's reign and its historical insignificance; a widely-venerated monarch who needed her government's permission even to change the drapes in one of her many homes.

Baird takes what is by now a standard approach to this paradox: she concentrates on the personal stuff and keeps the broader social and political issues of Victorian times firmly in the background. Readers might recall this approach from Stanley Weintraub's 1987 book "Victoria: An Intimate Biography "or Christopher Hibbert's 2000 book "Queen Victoria: A Personal History 2000." Even Elizabeth Longford's 1964 book "Victoria R.I." – by most measures still the best work on this monarch – found it expedient to balance its broader history with family drama.

Along this pattern, "Victoria the Queen" is a cheerful, chatty success from start to finish. Baird has that enviable combination of qualifications: a degree in history and a career in journalism. It's true she's prone to overstating things – at one point, for instance, she mentions the 39 years Victoria ruled after the death of her husband Prince Albert and rather absurdly claims, “we know little about this period.”

Her Victoria is a vivid, visceral creature: She shudders, she drops her jaw, she gasps, she grumbles, and so do all the people who come into her orbit, especially the handsome young man who would become her hard-working husband. “He walked into Windsor Castle, nauseated and exhausted,” Baird writes about his visit in 1839, “and looked up at the small figure looming above him on the stairs, the most powerful woman in the world.”

Victoria herself referred to marriage as a lottery (“the happiness is always an exchange”), and as all her earlier biographers have done, Baird makes it clear that the glowing central fact of Victoria's life was that she won this lottery: her bond with Prince Albert, the subject of Gillian Gill's delightful 2009 book "We Two," is the dramatic high point of "Victoria the Queen," although Baird also does a lively, excellent job of detailing Victoria's later years, a life that one historian described as “spent in high places but without luxury or extravagance and bounded by hard work.”

Baird paints a touching picture of those final decades, during which Victoria strove to feel alive despite the fact that the great love of her life was dead. She tried – sometimes clumsily but always earnestly – to be cheerful, to be involved, and especially not to be boring or pompous to her close friends and family members. She lost none of her arresting habit of being oddly authentic, and as Baird makes clear, she was dogged in her duty to the end. “A woman who had spent most of her life praying to be with her Albert in heaven was still begging her doctor for more time on earth,” she winningly writes. “There were more things to sort out, more disasters to prevent, more wars to fight, more soldiers to protect.”

"Victoria the Queen" ends on that note of devotion, and maybe, in a book about the founder of modern British constitutional monarchy, that's only fitting.