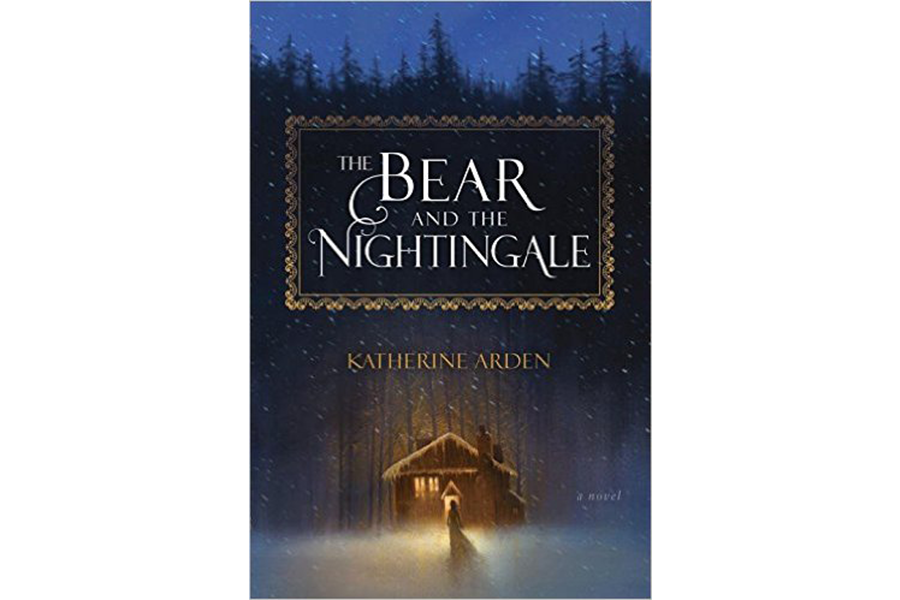

'The Bear and the Nightingale' charms with a tale set in in 14th-century Rus

Loading...

One night in northern Russia, a nobleman’s family sits down around the massive clay oven that warms the house. It’s late winter, and there’s nothing left to eat but black bread and watery cabbage, even for the wealthy, but no matter.

“No one was thinking of chilblains or runny noses, or even, wistfully, of porridge and meats, for Dunya was to tell a story.”

So opens The Bear and the Nightingale, the debut novel of Katherine Arden. Set in 14th-century Rus, a land of boyars (aristocrats) where Moscow is still made of wood and under the thumb of the Golden Horde, “The Bear and the Nightingale” combines Russian myths and medieval history to tell the story of a brave girl caught between old magic and the Russian Orthodox Church.

Vasilisa (also known as Vasya) is the youngest child of a Muscovite princess, who died giving birth to her, and a northern boyar. Her grandmother, called the beggar princess, was so beautiful that the czar married her when she rode tattered out of the forest; as a child Vasya is affectionately called “the frog.” It isn’t a luxurious life, even for the nobility. Fairy tales about the Firebird and Frost, the winter demon, are her family’s lone treat. But while a pious new stepmother soon puts an end to the storytelling, the characters themselves seem unwilling to vanish from the northern woods.

Arden wins points for coming up with one of the most believable explanations I’ve yet read for why a loving father would bring home a wicked stepmother: He had no choice. Pyotr Vladimorivich goes to Moscow to find a husband for his oldest daughter and a comforting, sensible woman to raise his youngest. Instead, thanks to the machinations of the Russian Metropolitan, he is forced to marry the czar’s mentally unstable daughter, Anna Ivanova, who longs for life in a convent.

In addition to his unwilling bride, Pyotr also brings home a gift for Vasilisa, one he was forced to accept to save his oldest boy’s life. After a drunk Kolya insults an immortal being, the man makes Pyotr take a blue jewel for Vasilisa.

“You are bringing gifts for your children, are you not? Well, I have a gift for your younger daughter. You shall make her swear to keep it by her always,” he tells the frightened father while holding a knife at his son’s throat. “You shall also swear never to recount to any living soul the circumstances of our meeting. Under these, and only these, conditions will I spare your son his life.” Pyotr, of course, promptly breaks his vows – the family’s devoted nursemaid, Dunya, persuades him to give her the jewel to hide until Vasilisa is grown. (There will be repercussions.)

Early reviews have compared the novel to Naomi Novik’s utterly delightful “Uprooted,” my favorite fantasy work of 2015, which used Polish fairy tales to anchor its complete turning-on-its-head of the story of the village maiden and the dragon. “The Bear and the Nightingale” doesn’t quite have the satisfying lift-off of that Nebula-winning novel – it devotes too many pages to a brother whose subplot never materializes, and hints about Vasilisa’s maternal line are never satisfyingly explored.

But Vasya remains a clever, stalwart girl determined to forge her own path in a time when women had few choices. I can also count on one hand the number of novels I’ve read set in medieval Rus – before Ivan the Terrible or Peter the Great.

And Arden constructs some clever parallels between Vasya and Anna. Stepmother and stepdaughter both share the second sight, but Anna is terrified by the “demons” she sees lurking in ovens and in the bathhouses. Vasilisa, earning her stepmother’s ire, befriends the house brownies and forest spirits who are growing weak as the church’s influence grows.

“We have never needed saving before,” Vasya tells the handsome priest, Konstantin, who is determined to drive out the old ways. The village had been balanced between the old faith and the new one, but that balance is upset with the arrival of the outsiders – with dangerous consequences that only Vasilisa seems to comprehend.

While Dunya claimed that, “fairy tales are sweet on winter nights, nothing more,” Vasilisa finds herself consulting their rules as she tries to keep her old friends from disappearing entirely.

Winters are getting harder and the forest more dangerous. The woods and stables are Vasilisa’s refuge, as Anna, goaded by Konstantin, grows more determined to break her youngest stepdaughter’s willful spirit.

The showdown between stepmother and stepdaughter is just one front in the battle, as Vasilisa has to save her village from things they have only heard about in the old tales. Not every fairy tale princess gets a happy ending, Dunya points out, but Vasilisa is willing to meet her fate – as long as it is one of her own choosing.