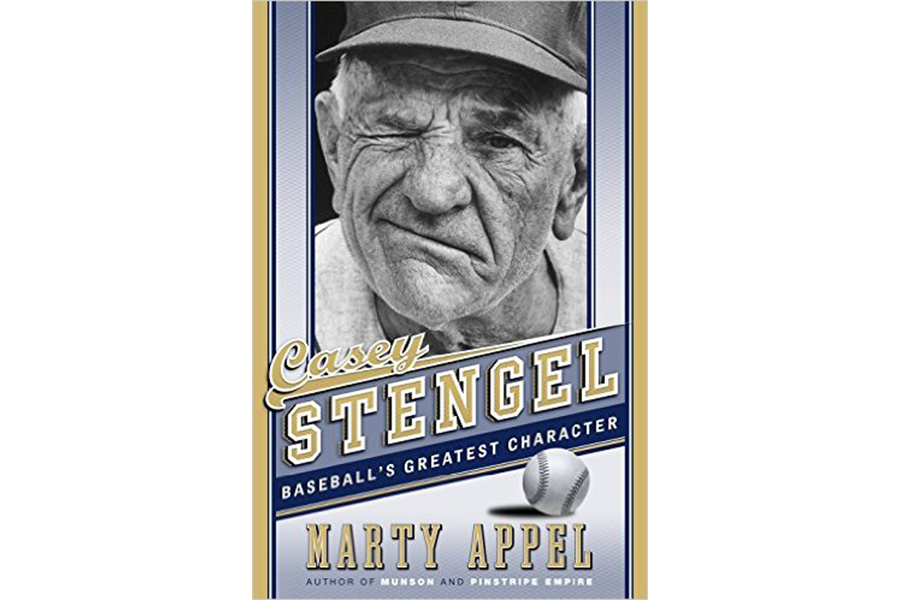

'Casey Stengel' profiles baseball's greatest character

Casey Stengel was not there in the very beginning, at baseball’s “Big Bang,” when a critical mass of interest in what would become America’s National Pastime erupted into rules, leagues, statistics, and such. It only seems like he was.

Casey competed against the legendary Connie Mack, who commenced playing ball in 1884. Early on, Charles Dillon Stengel would cahoot with the likes of Ty Cobb, "Shoeless" Joe Jackson, and Lou Gehrig, not to mention sportswriters such as Grantland Rice and Red Smith. He slammed the first World Series home run hit in Yankee Stadium, in 1923, playing against Babe Ruth.

It was a top-of-the-ninth, inside-the-park job that won the game, but afterwards Casey was so winded he couldn’t play in the bottom of the inning to help seal the victory. The man was totally old school: he drank, he smoked, he chewed, he brawled, and did a passable Irish jig. In them days, players left their gloves out on the field when they went in to bat. This peculiar practice pre-dated the Civil War.

For those who think modern players invented hot-dogging, or styling: Casey once hit a home run and stopped at second and third base to dust off each bag with his hat. And long before there was Yogi, there was “The Ol’ Perfessor,” who once lectured: “Good pitching will always stop good hitting and vice versa.”

In times like these, a book about Casey Stengel is just what our nation needs. And Marty Appel has delivered. Casey Stengel: Baseball’s Greatest Character is a wonderful romp through our collective field of dreams, from the medieval days of the sport to the modern era. The names alone are worth the price of admission: George “High Pockets” Kelly (don’t ask); Clarence “Cuddles” Marshall (Appel doesn’t tell); “Snuffy” Stirnweiss – and last but not least, “Marvelous” Marv Throneberry (who wasn’t).

There have been myriad biographies of Ol’ Casey and Appel draws on them, as well as newly available sources, including an unpublished memoir written by Stengel’s wife, Edna. Like Jell-O, there’s always room for more.

The country was still young when Casey was hitting and running. It fought wars to end all wars, and Americans dressed up when they went to the ballpark, the men in coats and ties. Baseball was like church, and Casey was an acolyte, worshipping at the altar soon after he was born in 1890, and right up to the end, at age 85. Appel, who has written more than 20 books about baseball, reports that Casey did little else: “He had no other hobbies: not golf, not card playing, not reading, not swimming, not tennis.” Elsewhere he points out that Casey and Edna had no children.

While it was a precarious way to make a living, professional baseball lured Casey out of high school and later dental school (he graduated from neither). He was left-handed, and he claimed there were no left-handed dental tools. Nonetheless, he labored at it during three off-seasons, and actually pulled a tooth once, during a procedure that he described as a wrestling match with an indigent patient. It would be hard to make this stuff up.

What Casey did besides baseball – and getting rich investing in Texas oil wells – was to talk baseball. He could really talk. When he became a manager of various teams, he talked to his players, to the opposing players, to the umps, to the press (AKA “his writers”), to fans in the stands, to anyone within earshot. When he coached third base he often carried on a spirited dialogue with the opposing pitcher, and at times would imitate his pitching motion (before Casey was considered a genius, later in his career, he was considered a clown). After games he would talk to all comers till all hours in the bars and lobbies of the hotels where his team was staying.

Casey conversed in his own language, “Stengelese,” which was characterized by the absence of punctuation or pauses, and, some say, information. But he made his points. After being unceremoniously canned by the New York Yankees – after he had led them to an unrivaled 10 American League pennants and seven World Series titles in 12 years – he said, “I’ll never make the mistake of being 70 again.”

Casey was, and arguably still is, 41years after his death, the very face of baseball – the wrinkled, winking, rubbery mug that epitomizes its joys and traumas. He had game, for sure. After the Bronx Bombers ditched him, he took up with those lovable losers, the New York Mets. And in 1964 – in perhaps his most telling baseball triumph of all – his ragtag cellar-dwelling crew, whom he satirically called the “Amazins,” drew more fans than the Yankees, who won the pennant that year. Casey managed to make losing popular.

To be fair, Casey was lovable except when he wasn’t. He kept his distance from his players and would occasionally humiliate them. For example, once he sent out a pinch hitter for Bobby Richardson in the first inning, and several times he placed future Hall of Famer Phil Rizutto last in the batting order – after the pitcher.

Appel writes, “Casey didn’t like [Jackie] Robinson, and it was mutual. A lot of it was competitive, a Yankees-Dodgers thing, when that rivalry was very strong. But some of it was surely subtle racism.” Robinson, who broke baseball’s color barrier in 1947, had criticized the Yankees for not having any black players (before 1955).

But later, in 1962, Casey showed his true colors: A Florida motel where the Mets were staying wouldn’t let a black player eat in the dinning room or use the pool – until the manager threatened to take his team elsewhere.

Casey Stengel died in 1975. At his wake, Bill Martin, who had played for Casey and later would manage the Yankees, got into a fight. Casey would have loved it.