'Hostage' tells the moving, suspenseful story of a kidnapping in the Caucasus

Loading...

Christophe Andre, a French administrator for Doctors without Borders in the northern Caucasus, had only been on the job three days when he was kidnapped by Chechens. He then spent 111 days as a hostage in the summer and early fall of 1997. Andre's captors asked the humanitarian NGO that employed him for a million dollars in ransom.

Guy Delisle, the marvelous cartooning memoirist and travel-writer, met Andre in 2000, and over the next 15 years learned, gathered, and then recreated in words and thousands of pictures, the details of Andre’s captivity. (We never find out how old Andre was at the time, but the drawings suggest he was in his late 20s or very early 30s.) If you’re familiar with Delisle’s previous work, you know his happy ability to make comical or poignant the smallest adventures in new worlds, in the style of something like realistic, uncolored Tintin adventures.

Delisle is a Quebec native who lives in France with his children and humanitarian NGO-employed wife. It was his wife's work that brought him to Burma (resulting in the dandy "Burma Chronicles") and Israel (which inspired his acclaimed book "Jerusalem: Chronicles from the Holy City").

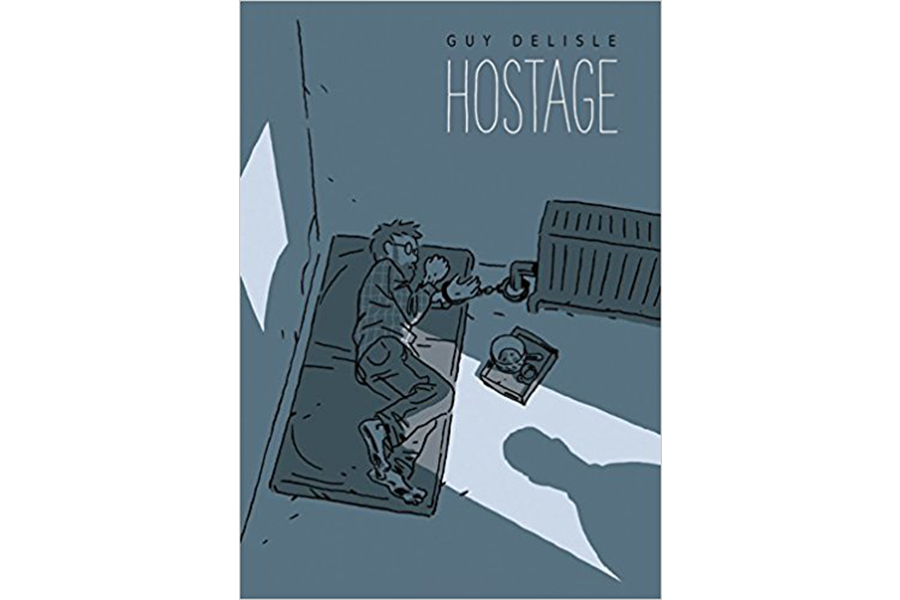

Hostage is more serious, moving, and suspenseful than anything Delisle has done before, despite the fact that it’s an anti-adventure for the most part, as Andre spends much of the 432 pages in "Hostage" sitting, sleeping, and waking up while handcuffed to a radiator or to an iron ring fastened to the floor.

The unfolding drama reminds me not only of the lawyer Stanley N. Alpert’s terrific 2007 memoir "The Birthday Party," about his kidnapping by New York City teenagers, but Leo Tolstoy’s greatest short story, “A Prisoner in the Caucasus,” which would’ve made a better title than "Hostage" (or the rather too suggestive "S’enfuir" of the original celebrated French version, if you don’t like your endings given away).

The bluish-gray tinting of the black-pen drawings has us peering into the shadows and carefully poring across the pages, which are for the most part boxed into five or more rectangles. We study Andre’s face as he contemplates his various possible fates. We gaze with him at the bare or decorated walls and at the shapes and visages of his captors, one of whom Andre nicknames, to himself, Thenardier, after the jailer in Hugo’s "Les Miserables."

Andre strives to keep himself level-headed: “I wonder if I haven’t skipped a day. I might have. Some days seem to go by in slow motion.… Other days, I feel like I’m going through a tunnel. I get lost in my thoughts, and suddenly it’s already night.” We see him notice the minute variations in the light and in the daily rations of soup; we see him imagine the conversations going on among his captors. He cannot speak to them or understand them, as he knows neither Russian nor Chechen. He tries not to imagine home, in France, where his sister is about to be married. He distracts himself by cultivating his memory of French military history, which Delisle neatly recounts for us.

(Perhaps, however, Delisle doesn’t make it clear enough that in the late ‘90s, Chechnya was trying to tear itself away from a new, post-Soviet Russia and that hostage-taking was a commonly partaken of war strategy.)

Despite the relentless isolation from everybody but his captors and their assorted family members and collaborators, Andre does not ingratiate himself with them. For the most part they seem, though heavily armed, to be amateurs.

Delisle, who is used to positioning himself as the butt of his own jokes, drawing on his own comical hypocrisies as a father and anxieties as a man and

cartoonist, never mocks Andre. Delisle’s sympathy is absolute and almost divine. The moment that seems to me the original spark of Delisle’s artistic creation is when Andre remarks: “It’s like I’m sitting quietly on a branch, watching myself make all these decisions from high above.”

That ghostly watchful sympathy is what Delisle infuses us with. As the time passes by, Andre rigorously tries to keep the calendar in mind, even as life continues with little external variation: “A bit of spilled broth and a smoke.… The two big events of my day.” His expectations of rescue make him ever attentive: “I tried to note as many details as possible. I figured they’d come in handy later. In testifying.”

Reading graphic nonfiction, playing that nimble match-game between words and images, feels something like watching a foreign movie with

subtitles, but the translation by Helge Dascher is perfectly transparent, and never reads like a translation.

I’ve tried to avoid descriptions that might give away the plot, but it’s as if Delisle has transformed Christophe Andre into a character like himself or Tintin, that is, someone who gleans and then reflects on the finest of sensory perceptions, because they might just save his life.

In an interview last year with Le Figaro, Delisle says Andre is “très content” with the book. And so would most of us be to have our stories told through the pen of Delisle.