The US government stole Lakota land. Her Jewish family benefited.

Loading...

It is ironic that author Rebecca Clarren’s Jewish ancestors, driven from Russia by brutal pogroms, ended up settling in the American West on land taken from Native Americans by violent force. As she sets out to examine in “The Cost of Free Land: Jews, Lakota, and an American Inheritance,” her family benefited from policies that encouraged hundreds of thousands of people of European ancestry to move west and claim Native American land.

Clarren has reported extensively on the American West. Her book grew from a desire to understand, and possibly redress, the role her family played – directly and indirectly – in the denial of land rights to Native Americans. She took to heart advice from Abby Abinanti, chief justice of the Yurok Tribal Court and a former judge for the California State Superior Court. Judge Abinanti advised her to look into what Jewish tradition teaches about repairing harm. Clarren writes, “She told me that, if I was lucky, eventually some Lakota might trust me enough to share their own cultural concepts of contrition, for how to make something right after you’ve done a wrong.” The judge told her, “Every culture has experience with being wrong, with finding a way forward.”

The book delves into the author’s wrestling with history, acknowledging harm, and seeking a path toward healing.

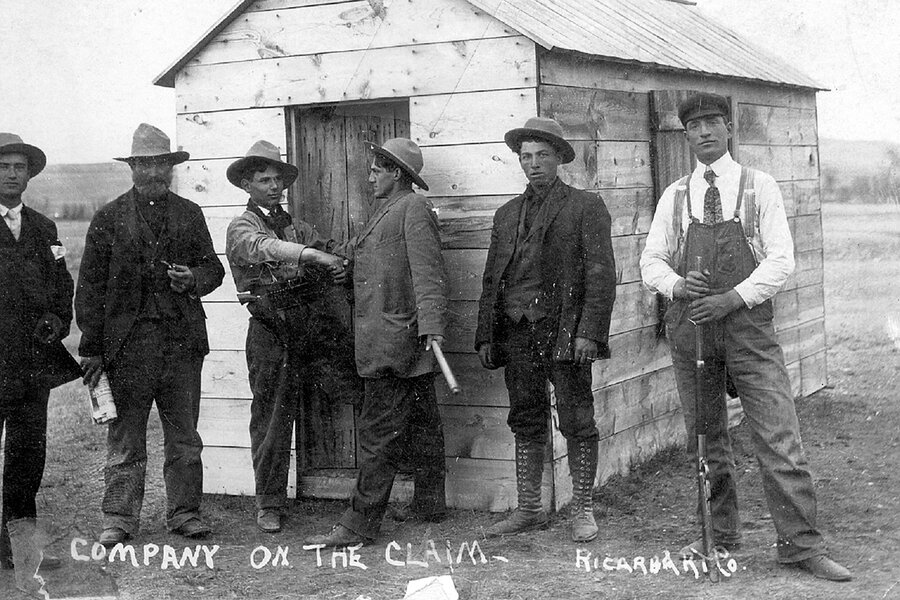

Clarren grew up hearing stories of how her relatives found new opportunities in the West at the turn of the 20th century. Like many immigrants at the time, they received 160 acres from the government, property they could keep if they could turn the wild prairie into farmland. The author writes, “Only after years of reporting in Indigenous communities did it dawn on me” that the acreage her ancestors were given, and which they expanded over time, had been home to members of the Lakota tribe for thousands of years.

Clarren began asking questions about what happened to the Lakota people before her family arrived. She researched firsthand Native American accounts of the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre, in which U.S. Army troops killed several hundred mostly unarmed Lakota men, women, and children. She interviewed present-day residents of the Pine Ridge Reservation, who attested to generations of harm that continues to affect their lives.

Clarren’s discoveries illustrate a repeating pattern of loss and tragedy for the Indigenous communities, in the face of President Andrew Jackson’s official declaration in 1834 that the prairie land west of the Missouri River would be “Permanent Indian Frontier.” For example, in 1877, a gold-laden landscape called He Sapa – known today as the Black Hills – was taken as U.S. property by means of an untranslated, convoluted treaty. The treaty was signed by the Lakota under coercion, which included threats of cannon fire and the withholding of food rations. When members of the tribe protested the illegal nature of the agreement, they were told by Indian Office bureaucrats that they “couldn’t pursue a claim of wrongdoing without Congress passing a law allowing such action.” In the 1920s, the mountains that are sacred to the Lakota community were carved with the faces of four U.S. presidents and became Mount Rushmore.

The Lakota people have long argued that the land was confiscated illegally and should be restored to them. In the 1920s, lawyers for the tribe filed suit, and in 1980, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the federal government owed the tribe $104 million for taking the land. But the Lakota rejected the settlement on the grounds that the land was never for sale. (The money was put into a trust, and the tribe has not touched it, on the grounds that acceptance would legitimize the government’s theft.) The tribe continues to call for the return of the territory. The legal battle for the Black Hills continues, one of the longest-running legal battles in American history.

Clarren’s book concludes with possible roads for healing. She points out that the practice of public truth-telling that appears in Jewish tradition is similar to Lakota customs. It’s a way of calling forth accountability and initiating repair.

Clarren’s research has now blossomed into a grassroots effort with the Indian Land Tenure Foundation to help Indigenous nations buy back their lands. In looking to the future, she writes that although “to wait for federal leadership on this issue is to delay justice indefinitely,” there’s hope that “Congress could be spurred to action if enough citizens lead by example.”