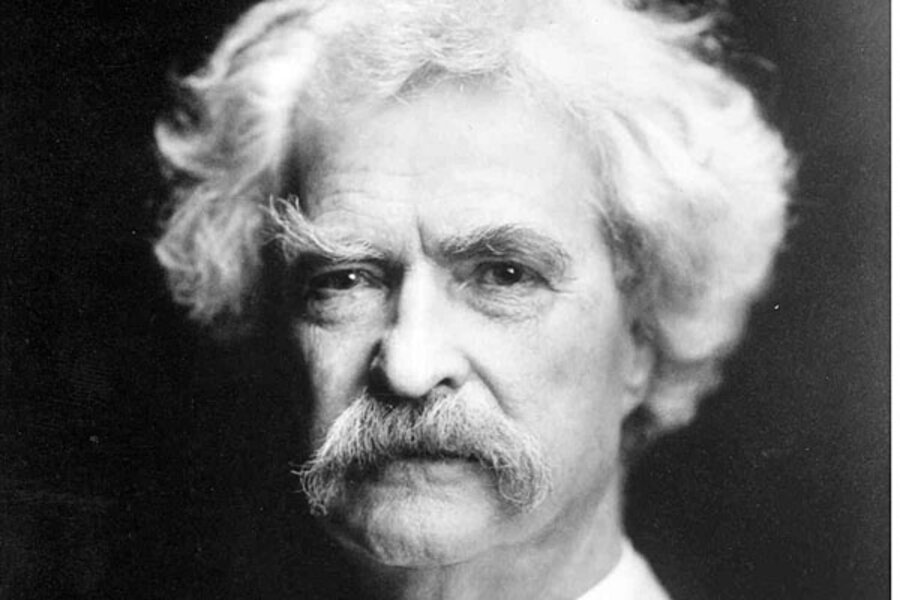

Huck Finn: Controversy over removing the 'N word' from Mark Twain novel

| MONTGOMERY, Ala.

Mark Twain wrote that "the difference between the almost right word and the right word is really a large matter." A new edition of "Adventures of Huckleberry Finn" and "Tom Sawyer" will try to find out if that holds true by replacing the N-word with "slave" in an effort not to offend readers.

Twain scholar Alan Gribben, who is working with NewSouth Books in Alabama to publish a combined volume of the books, said the N-word appears 219 times in "Huck Finn" and four times in "Tom Sawyer." He said the word puts the books in danger of joining the list of literary classics that Twain once humorously defined as those "which people praise and don't read."

"It's such a shame that one word should be a barrier between a marvelous reading experience and a lot of readers," Gribben said.

Yet Twain was particular about his words. His letter in 1888 about the right word and the almost right one was "the difference between the lightning bug and the lightning."

The book isn't scheduled to be published until February, at a mere 7,500 copies, but Gribben has already received a flood of hateful e-mail accusing him of desecrating the novels. He said the e-mails prove the word makes people uncomfortable.

"Not one of them mentions the word. They dance around it," he said.

Another Twain scholar, professor Stephen Railton at the University of Virginia, said Gribben was well respected, but called the new version "a terrible idea."

The language depicts America's past, Railton said, and the revised book was not being true to the period in which Twain was writing. Railton has an unaltered version of "Huck Finn" coming out later this year that includes context for schools to explore racism and slavery in the book.

"If we can't do that in the classroom, we can't do that anywhere," he said.

He said Gribben was not the first to alter "Huck Finn." John Wallace, a teacher at the Mark Twain Intermediate School in northern Virginia, published a version of "Huck Finn" about 20 years ago that used "slave" rather than the N-word.

"His book had no traction," Railton said.

Gribben, a 69-year-old English professor at Auburn University Montgomery, said he would have opposed the change for much of his career, but he began using "slave" during public readings and found audiences more accepting.

He decided to pursue the revised edition after middle school and high school teachers lamented they could no longer assign the books.

Some parents and students have called for the removal of "Huck Finn" from reading lists for more than a half century. In 1957, the New York City Board of Education removed the book from the approved textbook lists of elementary and junior high schools, but it could be taught in high school and bought for school libraries.

In 1998, parents in Tempe, Ariz., sued the local high school over the book's inclusion on a required reading list. The case went as far as a federal appeals court; the parents lost.

Published in the U.S. in 1885, "Huck Finn" is the fourth most banned book in schools, according to "Banned in the U.S.A." by Herbert N. Foerstal, a retired college librarian who has written several books on First Amendment issues.

Gribben conceded the edited text loses some of the caustic sting but said: "I want to provide an option for teachers and other people not comfortable with 219 instances of that word."

In addition to replacing the N-word, Gribben changes the villain in "Tom Sawyer" from "Injun Joe" to "Indian Joe" and "half-breed" becomes "half-blood."

Gribben knows he won't change the minds of his critics, but he's eager to see how the book will be received by schools rather than university scholars.

"We'll just let the readers decide," he said.