Who's your dead mentor?

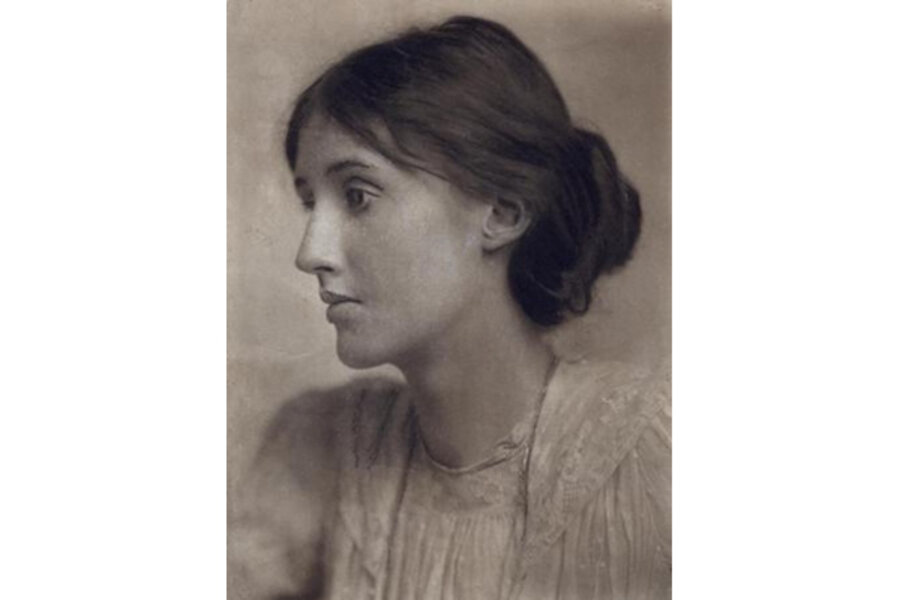

I have a great writing mentor – she encourages, she inspires, she challenges. Her name is Virginia Woolf, and she’s been dead for 70 years.

Here are a few reasons why all you writers out there should invoke the literary spirits of your own dead mentors…. or maybe, this Halloween, your dead mentor will find you.

1. Dead mentors help you see beyond the buzz

We’ve seen it time and again – one book’s success inspires a thousand emulations. Helen Fielding's "Bridget Jones's Diary" was a runaway bestseller; the popular new genre chick lit was born. Stephenie Meyers’s "Twilight" hooked readers of every age, promptly spawning the teen vampire lit multiplying on young adult bookshelves.

It’s easy to be dazzled by current success stories because they are, clinically speaking, hot. More often than not, though, hot trends cool. The fame of fewer and fewer books withstand the passing of time. After all, how many of us can name more than five authors – other than Shakespeare – from the Elizabethan era?

Focusing on an author from the past, even if her style is different, allows the writer to look at essential qualities of writing. A romance writer could improve dialogue by reading Jane Austen’s banter between Elizabeth and Darcy; a sci-fi writer could improve setting by reading George Orwell’s descriptions of Room 101. It’s not about who just scored the biggest deal from Random House. It’s about the truth and talent that transcend time.

2. Dead mentors are recession-proof

That eight week novel-writing class taught by a hip author might seem like the answer to all of your writerly prayers, but times are tough. Classes and conferences can be great, but they’re also expensive, and after a while, they add up.

Not only are dead mentors are free, but they are forever at your beck and call. No need to spend a month’s mortgage payment on a pricey class. Just jump in your sweats after dinner to find inspiration from "The Outsiders" and remind yourself that if S.E. Hinton can write a great book at 16 years old, so can you at 37.

3. Dead mentors help you help yourself

Though it’s tempting to throw a freshly written story at a mentor and plead, “What do you think? What should I change? What should I keep?”, it’s also a little self-serving. This places the burden of reflection on the mentor instead of the writer taking responsibility for her own work. Dead mentors can’t answer specific questions; rather, we can use their thoughts and words to answer our questions for ourselves.

Erica Wagner, literary editor of "The Times," does just that with her own dead mentor, Washington Augustus Roebling. “He once said that ‘[y]ou can’t get out of the work life lays on you,’ and that’s something I think of often,” says Wagner, who has most recently authored the novel "Seizure." “If I am struggling, if I feel like giving up on something – whether it is my writing or something in my life – I think of Washington and what advice he would give me. ‘Keep trying,’ he’d probably say. ‘You will find a way. Look clearly at your situation and work towards a solution.’”

In the same manner, Virginia Woolf’s diary is a lifeboat for those writers drowning in despair. “I foresee,” Woolf wrote regarding "Mrs. Dalloway" on June 13, 1923, “… that this is going to be a devil of a struggle. The design is so queer and so masterful. I’m always having to wrench my substance to fit it. The design is certainly original and interests me hugely. I should like to write away and away at it, very quick and fierce. Needless to say, I can’t. In three weeks from today, I shall be dried up.” Any writer can find solidarity in Woolf’s excitement and confidence mixed with insecurity. The benefit is twofold. We can read "Mrs. Dalloway," admire its strength, and strive to write as effectively as Woolf. Yet we also can connect to her as writers in reading her diary entry by sharing in the often confusing, uncertain process of writing. In this way, she becomes the best mentor, the best teacher: someone who sets standards of production high as well as someone from whom we learn the importance of process.

The job of the writer is to think, What would my mentor do in this situation? What would he say? and take ownership of her problems and solutions, as Wagner does with Roebling and as Woolf offers with her diaries and literature – as opposed to calling a living mentor with a frantic “Solve my plot problem now, today!”

4. Dead mentors help you to become a better reader

In her book, "The Faith of a Writer: Life, Craft, Art," Joyce Carol Oates writes, “[I]f you read, you need not become a writer, but if you hope to become a writer, you must read.” Translation: in addition to daily writing, working a day job, cooking dinner, and sustaining real-life relationships, writers are expected to read voraciously if they hope to succeed.

Living mentorship often takes place in the form of phone calls, emails, coffee dates, and time-consuming writing classes. Save your time and kill two birds with one stone. Looking to your dead mentor for advice means that, nine times out of ten, you’ll be reading. Whether it’s your dead mentor’s novels, poems, letters, diaries, or biographies, “interacting” with literary ghosts accomplishes two goals: you get your advice while honing your close reading skills – which, according to Oates, will make you a better writer.

5. Because the “prose” say so

Accomplished writers agree that leaning on the words of authors past is essential. “I have a zillion dead mentors,” says Helen Schulman, American novelist and recipient of numerous awards, including a Pushcart Prize. “That’s what a lifetime of reading does.” Francine Prose also makes the case for dead mentors in the first few pages of her book, "Reading Like a Writer: A Guide for People Who Like Books and for Those Who Want to Write Them." “Long before the idea of a writer’s conference was a glimmer in anyone’s eyes, writers learned by reading the work of their predecessors,” she writes. “They studied meter with Ovid, plot construction with Homer, comedy with Aristophanes; they honed their prose style by absorbing the lucid sentences of Montaigne and Samuel Johnson. And who could have asked for better teachers: generous, uncritical, blessed with wisdom and genius, as endlessly forgiving as only the dead can be?”

– Jessica Rosevear blogs at JessicaRosevear.com where she focuses on the intersection of teaching and writing.