In Zimbabwe, hope behind the horror

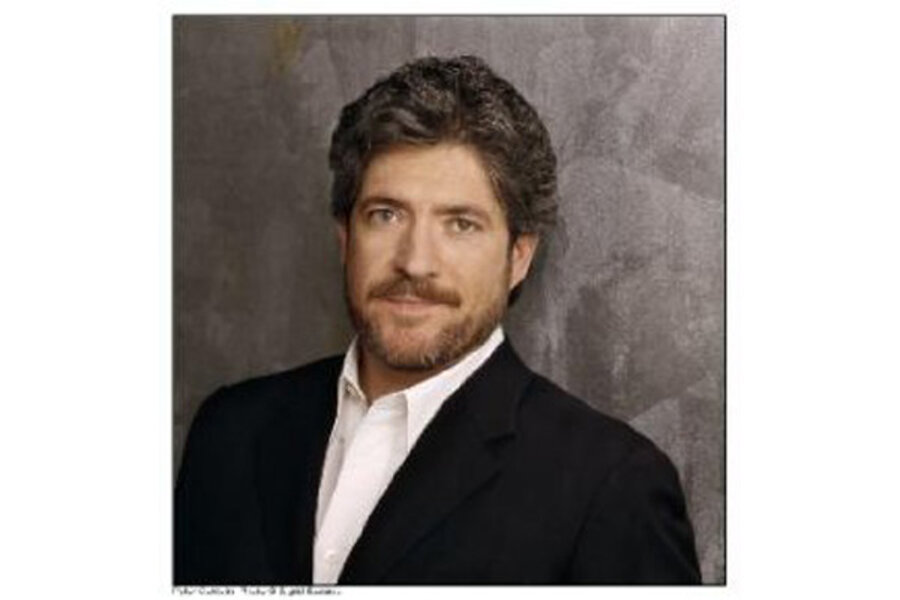

Author and journalist Peter Godwin returned to his home country of Zimbabwe to bid a bitter farewell – at long last – to the dictator Robert Mugabe. Instead, as he tells in his new book "The Fear," Godwin watched a crumbling African country reach new depths of violence and tragedy after the 2008 election, all beyond the vision of forbidden foreign journalists.

I found "The Fear" to be both immensely readable and overwhelmingly sad. Monitor reviewer Tracey Samuelson refers to Godwin's "heartbreaking journey of witnessing," saying "it becomes the reader's burden as well."

10 novels in translation you should know

For his part, Godwin refuses to accept the idea that Zimbabwe is a place without hope. In an interview he did with me this week, Godwin ponders the helplessness of victims of violence, recalls a US ambassador's breathtaking moment of decision, and looks forward to a better future for a place with a horrific present.

Q. You visit hospitals and talk to many victims of the Mugabe regime's political violence who had no way to fight back against gangs of men. This is in sharp contrast to, say, Libya, where rebels at least have some weapons. Do you think of the Zimbabwe victims as helpless?

Rather than the word "helpless," I might choose the word "vulnerable." They tried to make their voices heard and were very exposed and vulnerable. They couldn't fight back and didn't fight back. They didn't have weapons.

These are such important voices: they sort of shame us in a way, these people across the social, economic, and education spectrum. These are people who are sacrificing, ordinary people putting their heads above the political parapet for the first time. Many of them are not die-hard political activists for years and years. They're just ordinary folks who said it was enough.

Right from the beginning, they've made it clear that they are peaceful. They take pages from Gandhi and Martin Luther King. They've pretty much stayed to that, but when Mugabe turns on them and unleashes this furious violence, they are very vulnerable.

That seems to make them less deserving of international help. The message these Zimbabweans take away is that if you want the rest of the world to come to your aid, you have to start a civil war.

Q. Is there anything uplifting to be found in your book, which describes a devastated country?

When I went to Zimbabwe in 2008 and again in 2009, the people I met and their stories were so compelling that I actually find that I came away inspired. Once I'd spoken to those people, it never occurred to me not to write a book. I have to do everything to amplify their voices.

I felt it was a really important story, and one that really transcends the particulars. It's not just a little story about a little country in Central Africa. It's more than that: it's a story about the human condition, a really compelling story with an astonishing trajectory.

Zimbabwe was held out generally as the great hope for Africa. It was always cited as an example of Africa working, with the highest literacy rates and one of the highest GDPs. It worked: this was Africa at its best. Then it became Africa at its worst in an incredibly short time, really in 10 years.

It just beggared belief. It feels like something out of King Lear: you have this one person, Robert Mugabe, who becomes this icon and then refuses to go and would rather pull the pillars of the temple down on everyone's head than leave.

Q. At one point in the book, you wonder whether whites in Zimbabwe – who now make up a tiny portion of the population – should just leave.

In a moment of weakness, I said maybe the best thing for whites to do is get out of the way. But the people I was with, who were mostly black Zimbabweans, turned on me and said that's not the way it is.

For the last 10 years, the opposition has been fully multiracial. You have a kind of bonding across races, everybody being in the trenches together.

Q. The whites aren't universally popular, however.

Every time anyone sees a white face among the opposition, that gives grist to the mill among Mugabe's people. They accuse the opposition of being with the imperialists. We provide Mugabe with cheap propaganda points.

[Spoiler alert: If you plan to read "The Fear," skip this next section since it gives away a dramatic moment in the book.]

Q. You write about how you watched as Jim McGee, America's ambassador to Zimbabwe at the time, stood up to Mugabe's police forces and even dared them to shoot him. This happened while they tried to detain him and other diplomats during a tour of Zimbabwe areas hit by political violence. Was McGee – an African-American and veteran of the Air Force during the Vietnam War era – courageous or foolish or both?

That's the mold [McGee] is cast in: he's not a guy to shrink back. We'd spent the day talking to torture victims, and then when you first get sight of the people who are responsible for it, you've got this pent-up anger on behalf of all these victims.

In a sense, it may have been a little thing, but it was totemic and important. He's got diplomatic immunity, and he's the American ambassador. He was in danger. You never know, a junior soldier could have just shot him.

Jim knew that, but he was definitely pushing the envelope quite deliberately. At that point, we all felt hopeless. There was next to no media coverage about what was going on, and we were exasperated and frustrated and angry and feeling kind of powerless.

Q. Where do you see hope in Zimbabwe's situation?

The Zimbabweans have proven to be an amazing example of not giving up. The hope is in the pages of the book, in the people you meet. All the people want is free and fair elections. If democracy is restored, they can rehabilitate it amazingly quickly. The place has got such potential, and there are still institutional memories of how things work.

You realize that Zimbabwe doesn't need someone to come in and nation-build. It's got a nation. It just needs to express itself.

Randy Dotinga is a regular contributor to the Monitor's book pages.