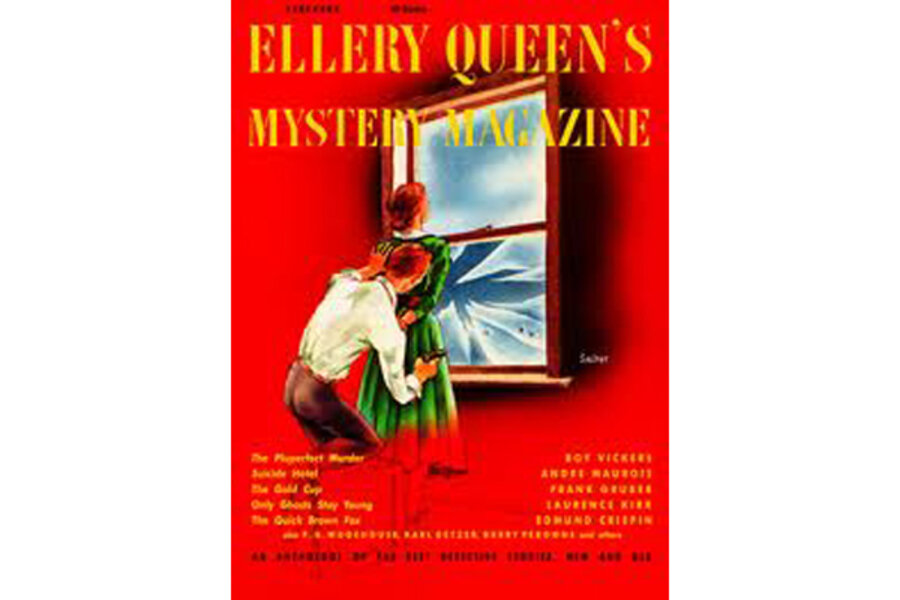

Mystery Magazine: At 70, Ellery Queen's publication still has a clue

Loading...

When Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine first appeared in 1941, the detective story was more read than respected, frowned upon by the fusty gatekeepers of the literary establishment.

Over the next seven decades, the mystery novel has clawed its way to a better reputation, although it still doesn't get invited to the best dinner parties. (Good thing: Knocking off the host is considered gauche.)

While they don't get as much attention, mystery short stories have tagged along for the ride to semi-respectability. In large part, that's thanks to what fans like to call EQMM. As always, it's a compilation of both new and classic mystery short stories along with columns about topics like books and, now, sites on the Internet.

The last couple of decades have been rough on the monthly magazine, which now has about a readership of about 30,000. But Janet Hutchings, its editor of 20 years, says the Internet era is boosting EQMM's profile and leading to a rebirth. In an interview this week, we talked about the evolution of mysteries, the long odds against getting your story published and the value of violating writerly rules.

Q: What do you like best about short stories?

It's so complete. You read it in one sitting, and the impact is different just because you're reading it all at once. That's what I enjoy the most.

Q: What was behind the founding of the magazine by Frederic Dannay, who with Manfred B. Lee created the pseudonymous author Ellery Queen and gave their detective the same name?

A: Dannay wanted to show the world that mysteries should be a respected genre. He believed that every great writer in history had written at least one mystery.

He also wanted the magazine to represent every aspect of the genre. When [detective story author] Dashiell Hammett got in trouble during the McCarthy era, Fred put out his books. It wasn't just his friendship. He wanted to keep that area of the genre going strongly.

Q: How has the magazine evolved?

A: It's changed with the times. The stories are edgier sometimes, and fewer people are writing traditional whodunnits. That's been the case at least since the 1980s, and then we lost Edward D. Hoch, the best of the puzzler writers. [Hoch, who passed away in 2008, wrote hundreds of stories for the magazine and became famed for his locked-room mysteries.]

But we're seeing more locked-room mysteries lately. It's starting to come back. And we're seeing a lot of diversity, as with the pure crime stories that Clark Howard writes.

Q: How are mystery novels changing?

A: The biggest change I've noticed is that there's a lot of use of sexual language and profanity. But that just isn't our readership.

Q: Female authors remain a major force in the mystery world, and the last few decades have cemented their place as writers of psychological thrillers and private eye novels instead of just classic whodunnits. Are women making inroads in short stories?

A: At least two thirds of our submissions are by men. I don't know why that would be. It seems to occur more with the short stories.

Q: EQMM's sister magazine is Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine, which is still around. How does it differ from your magazine?

They publish basically the same types of mysteries, although there's probably a little more emphasis on the supernatural –ghost stories – and they publish a humor issue.

We definitely publish more stories from other countries. Each month we run a story in translation, and for years about 20-30 percent of each issue has been from Britain.

Q: EQMM has a large stable of regular writers, but it also regularly publishes first-time authors. How many submissions do you get from newbies?

A: I'm getting about 250 a month, and we run about 10 first stories a year, so the odds are about 1 in 275. That's not bad compared to a lot of literary magazines, some of which get even more submissions.

Q: What advice do you have for wannabe EQMM writers?

A: In all these years and all the writers conferences I've gone to, I listen to the advice people get and think, for every rule they're told, someone will break it successfully. Like, "Have a great opening line or you won't grab an editor's attention."

The most popular theme, especially for new writers, is the spousal murder. I do get tired of seeing that unless it's done really cleverly. That's a scenario we could definitely see less of. And there are people who take things from news stories. There's not necessarily anything wrong with that, but you'll go through periods like when we were getting all sorts of stories about child abuse. It isn't a good subject for us.

Q: I was reading the current 70th anniversary issue and noticed modern touches like cell phones, email and even an assault weapon in a story about a bank robbery. Those, of course, weren't in stories when I read EQMM as a teenager. (Never mind when that was.) How has technology affected the stories themselves?

A: It's become a lot harder to plot stories, whether it's a book or a short story, unless you set a classical mystery in the past. With all the communication we have, it's harder to keep any kind of secret.

Q: How has technology affected the magazine itself?

A: The last 20 years were rough, or at least the last 15 of them. We lost American Family Publishers and Publishers Clearing House, the main agencies through which we sold the magazine. All magazines were affected.

Now, we have podcasts and e-editions, and I read submissions entirely on a Kindle. It's hard to think of anything that's being done that we're not into. It's changed everything. We've turned a corner, and I think this is actually a good time for the magazine.

Randy Dotinga is a Monitor contributor.