Biographer D.T. Max: getting inside David Foster Wallace's head

Loading...

David Foster Wallace, perhaps the biggest literary star of our era, didn't spend his childhood buried in a book. Instead, he watched TV. A lot of it.

It did not rot his brain.

Instead, Wallace would become fascinated by pop culture and spend his career trying to untangle its influence and power. He questioned ironical detachment and tried to write what he called "morally passionate, passionately moral fiction." He'd write mammoth novels, short stories and journalism.

Born near the cusp between the Baby Boomers and the denizens of Generation X, Wallace became a touchstone for both. But he couldn't vanquish the demons of mental illness and killed himself four years ago this month.

D.T. Max, a staff writer for the New Yorker, has spent the last several years trying to understand the enigma of a man who could embrace life so fully – and enlighten the rest of us about it – yet not wish to go on.

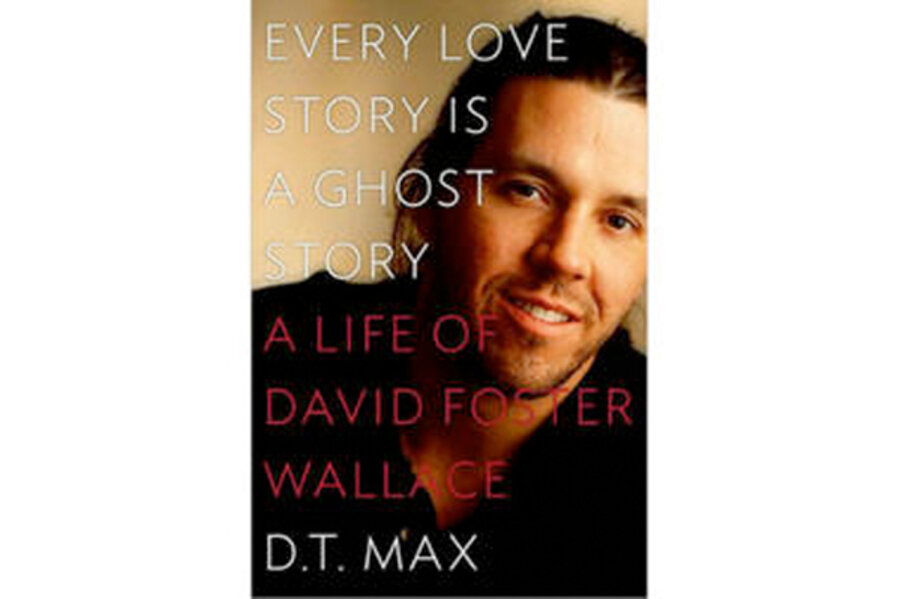

Max's new biography, "Every Love Story Is A Ghost Story: A Life of David Foster Wallace," is a hit with many reviewers. I met with Max near his home in northern New Jersey and asked him about Wallace's fascination with popular culture, his messages about life and the impact of his depression.

Q: What surprised you as you researched the book?

A: He has this image as "Saint Dave," this person who can show us how to live in a distressed world. After he died, there was this outpouring of grief from so many people, even those who hadn't read much of his writing. They knew him as a kind of hip homilist, a cultural sage.

The book obviously shows him to not be a perfect human being. The level of his imperfection was a surprise to me, but I also came to understand that the identification with him isn't that he's perfect. It's that he teaches something about life.

He had this deep concern for people in his writing and in his [famous] speech at Kenyon College. He cares whether the reader has a full life or not, whether they go through life awake or not.

He had this stance of being unironic but not simple minded, curious without being intrusive, empathetic without being sloppy.

Q: Did you feel like a detective trying to solve a mystery?

A: The mystery about David was about how someone so immensely talented, creative, and successful could feel so bad about himself no matter what. He hated criticism, but he also hated praise. He hated illness, but he also hated being well. I wanted to understand what that person was really like.

Q: I'm fascinated by his childhood and how much TV he watched. Some writers are proud of themselves for never having encountered pop culture. They don't own a TV, they don't watch TV. They act like they don't know what a TV is. But for Wallace, pop culture is all over the place. He's not superior to it. What can we make of that?

A: Not only was he was acquainted with pop culture, he thought he was addicted to it. He said his primary addiction wasn't to marijuana or alcohol, it was to television. David, with his anxiety and depression, found television fundamentally soothing: He was addicted to narrative. He said the narratives were too easy, too smooth, the endings too pat. But his sister says in the book that she didn't know anyone who had a need for TV like David had.

Q: Did the depression within him inspire his writing? Did he need it to give him inspiration?

A: I don't think so. I don't think he's that kind of writer.

The despair was something he feared enormously and ran from his whole life. It would be more accurate to say to say his tendency toward gags and humor writing – he was a very funny writer – was probably to some extent an attempt to outrun the despair.

He had that massive brain that always kept him company and always tormented him.

Q: What can we learn from David Foster Wallace?

A: He's not a cautionary tale about flying close to the sun. His story is much more about an insistence on never being content with who you are or what you've written.

Here's a guy who could have been a well-known literary author and lived in his little literary persona. Instead, David insisted on trying to reach people in this highly unusual and emotional way and show people, as he does in that Kenyon College speech, that he cares about them and how they live their lives.

For a guy like David who wasn't naturally caring, this shows that you can push the edges of your natural comfort zone in order to reach people.

Another lesson is that often it's the simpler truths that carry you forward, and the complex truths that hold people back. If you can simplify what you're here for and who you want to be for people, you can achieve far more than if you insist that life is so complicated.

Randy Dotinga is a Monitor contributor.