Boston Marathon bombing: how it compares to the 1920 Wall Street attack

The bomb exploded in the very center of American capitalism on a weekday afternoon, just steps away from the New York Stock Exchange and the famed statue of George Washington at Federal Hall. Thirty-eight people died and hundreds were injured, several losing limbs to the explosive power of an estimated 100 sticks of dynamite.

As in Boston this week, the bomber had rigged the device to not only kill but maim through the spread of shrapnel packed into the bomb.

The United States would not see a deadlier attack of terrorism until a spring day in Oklahoma City.

Despite its horrific toll, the Wall Street bombing of 1920 is largely forgotten today. New York City instantly cleaned up the scene and moved on. No one was ever charged with the crime, and no memorial was ever built. Only the pockmarked stone of the former Morgan Bank building remains as a grim if subtle reminder.

The bombing is worth remembering. It reminds us of an era when terrorists horrified the world but had yet – until that September day – to make a point of targeting ordinary Americans in public. And it shows how the US refused to take the wrong path in the wake of tragedy.

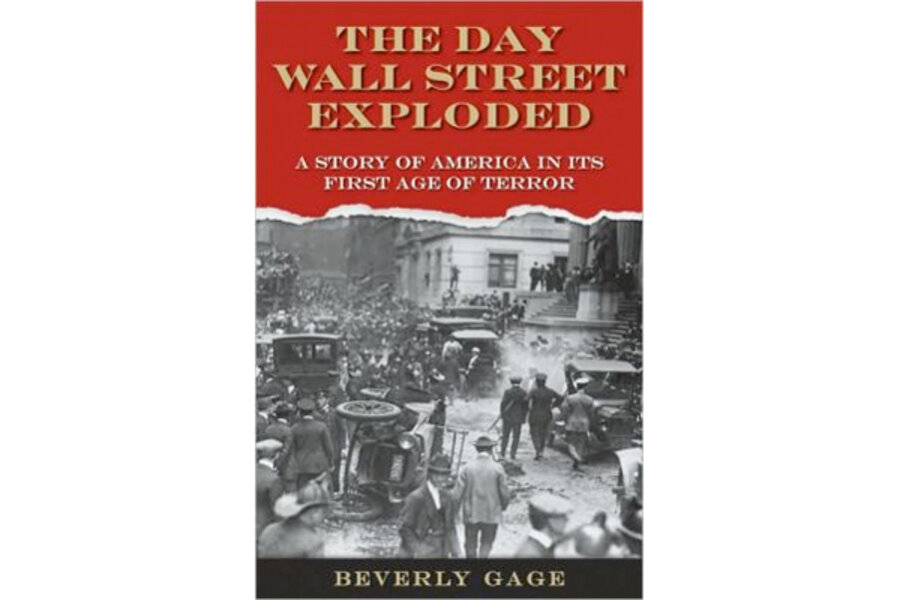

Beverly Gage, a history professor at Yale University, wrote the definitive book about the attack, 2009's "The Day Wall Street Exploded: A Story of America in Its First Age of Terror." I asked her to reflect on the similarities between the bombings in New York and Boston, the evolution of terrorism in the US, and the legacy of that distant but familiar day of horror.

Q: What struck you as you learned about this week's bombing in Boston?

A: We think of these kinds of mass bombings as being symptomatic of the terrible things about our own contemporary world, at least since Oklahoma City. But this kind of event has been going on as long as technology has existed to set off bombs in crowded places.

Q: Was this fact of history the reason you wrote the book?

A: I set out to write that book because I came across a mention of the 1920 bombing, which killed 38 people and injured hundreds more people, many of them quite seriously. I was shocked that I had never heard of this. What's going on that allowed this big event to be lost to history?

The other thing that surprised me was how many people at that time were saying "Ah ha! Of course. We all knew this would come."

I thought, "What? How did they assume that?"

I began to look not only into anti-Wall Street history but also the long history of anti-capitalist bombings that had been going on for 30 to 40 years, going back to the Haymarket bombing in 1866 [in Chicago], the most famous of them all, all the way up to the bombing of the Los Angeles Times in 1910, the bombing at a Preparedness Day parade in 1916 in San Francisco, and a series of coordinated bomb attacks in a number of different American cities, including the bombing of the US attorney general's home in Washington D.C.

Q: What made this bombing stand out as unusual?

A: A lot of the previous bombings had been much more targeted, very deliberate acts of assassination aimed at particular people. This one hit messengers, tourists, and several veterans of the first World War who had gotten jobs on Wall Street and were killed at home instead of on the fields of France.

This was one of the reasons people thought this really might be an accident. Even those few political revolutionaries who embraced terrorism most often were talking about deliberate acts of assassination or political violence. This level of mass violence was unusual and tragic.

Q: Had terrorism evolved from targeting specific types of people to the public at large?

A: Terrorism revolves around using targeted forms of theatrical violence to foster social instability. In modern form, it goes back to about the mid-19th century, when you began to get technologies like dynamite. You could plant a bomb and leave and wait for it to go off. As anarchists of the 19th century would have said, it allowed people to strike anonymously from afar.

But much of the discussion tended to be about targeting business and political leaders. One of the questions is: How did we get from that vision to where we are today?

Part of the story is that there's a certain kind of escalation built into terrorism itself to maintain the ability to shock and public attention.

Terrorism is fundamentally about capturing people's attention. One of the reasons 9/11 was so shocking is that we hadn't seen anything quite like it before.

Q: Who was behind the bombing?

A: The main suspects were either anarchists, who are the most likely culprits by the judgement of history, or communists.

The country had been through a whole series of crackdowns on political radicals already. The most famous was the Palmer Raids, a series of deportations that had been aimed at anarchists and communists. By the time the Wall Street bombing happened, there had been a pretty public backlash because those efforts had been poorly handled.

You got an elaborate effort to go beyond the Palmer Laws, to crack down, have elaborate arrests, and even outlaw criticizing capitalism. A lot of that doesn't come to much because they don't solve the bombing, and there's never a lot of certainty about what actually happened. Things end up remaining in this uneasy state, and people move on.

Q: Why isn't the bombing remembered today?

A: The generation of people who lived through this bombing all remembered it. The day after it happened, the first 17 pages of the New York Times were devoted to that event in particular.

But there was never a memorial, and the leaders of Wall Street were pretty serious about not wanting to bring it up or reference it. They had a pretty deliberate strategy of letting the event recede into the past.

There isn't really anybody, except the families of the victims, who had a lot of interested in maintaining the memory of the bombing. The radical left didn't want to remind anyone of this, as it was a hugely discrediting event. People on Wall Street didn't want to preserve that memory. And the police investigators who utterly failed to solve the Crime of the Century had very little interest in keeping this going.

Q: Is there something positive we can take from this story?

A: In many ways, it's a story about political restraint.

Even in the face of a really serious tragedy, great mourning and very heated discussion and suspicion, people for the most part avoided jumping to conclusions and engaging in the kind of most draconian reaction that was being suggested at that moment.

However, had the police actually arrested a genuine suspect and had a big show trial, the story of the consequences would have been very different.

Randy Dotinga is a Monitor contributor.