'On the Fireline' author Matthew Desmond recalls life as a wildland firefighter

A decade has passed since Harvard University sociology professor Matthew Desmond spent his college summers working as a wildland firefighter in northern Arizona. But he hasn't left the woods behind.

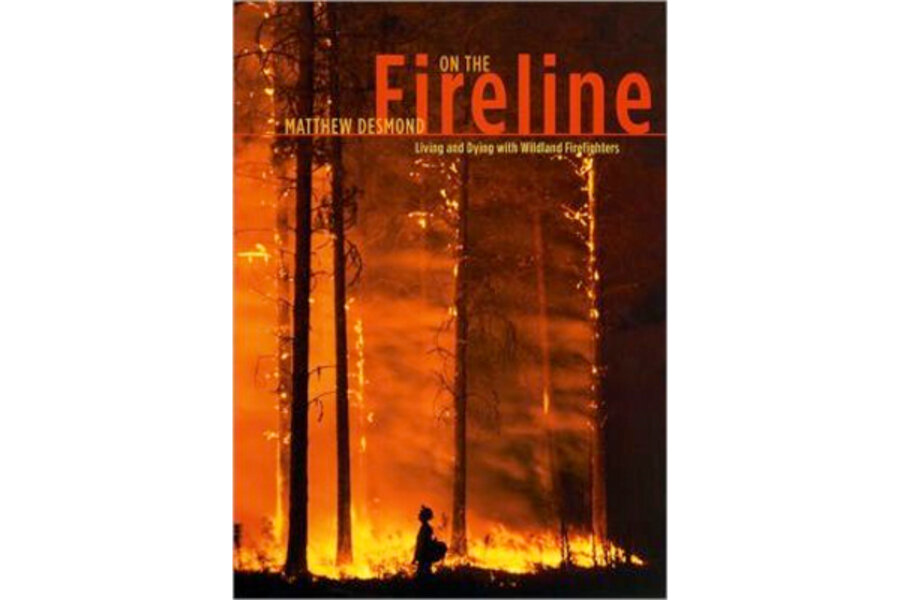

Desmond relied on his experiences to write his 2007 book On the Fireline: Living and Dying with Wildland Firefighters. And yesterday he found himself on the phone trying to reach his friends in the rugged land where he grew up. He wanted to know if they were OK.

Details are still emerging about the deaths of 19 firefighters near the Arizona city of Prescott. They were caught in a firestorm while trying to fight a wildfire that threatened the tiny town of Yarnell.

Desmond grew up in nearby Winslow, Ariz. (yes, the little town from the song) and spent many scorching summer months waiting to rush toward smoke on the horizon.

I asked him to describe the risk and appeal of a dangerous job. Rural firefighters like to complain that city firefighters have more "street cred" and attention from females, he says, but there's another side to the coin: "You feel like you own this piece of America."

Q: People think of Arizona as being a desert state, but you fought fires in the woods, not too far from a ski resort or two. What was the landscape like there?

A: Arizona has a lot of different climates. This area is a forest with many ponderosa pines. It gets snow in the winter, but it can dry out quickly, and Arizona has witnessed high temperatures and drought in the last few years. They've also experienced a massive beetle infestation, which dries out trees and makes them tinder sticks. Along with other things, these have all contributed to massive fires in Arizona over the past 10 years.

Q: How did you become a firefighter?

A: This was what a lot of us, mainly young men, did in the summers in northern Arizona. This is how I put myself through college. I fought fires in the summer, and then I went back and did it again when I went to graduate school.

Q: What was the appeal of this life for you?

A: At the station, it's 45 minutes away from the nearest anything. We live out there, we cook and eat out there, and when there's no fires and we get off at 5, you have the whole rest of the night to yourself. You feel like you own this piece of America in a way.

Q: What backgrounds do the firefighters have?

A: They tend to have rural, working-class backgrounds. Some folks' dads would be mail carriers, postmen, or work for the railroad in rural Arizona. Or maybe even high school teachers. My dad was a preacher.

Q: What would people do during the long off season?

A: You have college kids who go back to college and some guys who just collect unemployment and wait until the next season or take odd jobs like working in the family restaurant.

Q: How did firefighters deal with the tremendous risk they face?

A: We dealt with it by telling ourselves that if we're competent and follow the rules, it wouldn't happen to us. A lot of us who grew up in the country, hunting and fishing, being very familiar with the woods and dirt roads, have the skill set you need to fight fire. You come with that. It's your background.

You take all those skills and you're told about the 10 standard fire orders, which are like the 10 Commandments. You're told to follow those, and you'll be OK. But there's a cost to that.

These are young men in their early 20s. On one hand, getting young men to follow the rules and pay attention, emphasizing the mistakes that they can make, helps with a kind of situational awareness. On the other hand, it can cultivate a kind of culture where what's valued most is your individual competence.

Q: How is that a problem?

A: That kind of self-reliance is dangerous for firefighters. It could lead to a breakdown in the chain of command and leaders not being listened to. It can lead to poor teamwork.

Q: What do people misunderstand about what wildland firefighters do?

A: There's a narrative that these country kids do it for the rush and the adrenaline. There's something to that, but it fades over time. When you fight fires for a few seasons, you know what to expect. Your heart doesn't race as much as it did.

Some say it's for the money and the paycheck, that it's a good way to stock up. It's true that you're in the middle of nowhere and you can't spend that much money. And if it's a hard fire season, you're working overtime and getting hazard pay. But it's not really about that, either.

It's more about the land, about being able to work outside and not being behind the desk. "The desk" epitomized this terrible existence.

And it's a way to ply the skills you gained growing up in the country in a profession that values those skills, like how to wield a chainsaw and how to drive a four-wheel drive.

Q: Would you go back?

A: My life's very different now, but I miss it.

It's hard work and it's grueling, but it's also very rewarding and satisfying. Fire itself is very beautiful, and there's an attachment to fire that firefighters have.

It's not a pyromaniacal fascination but a kind of intimacy that you get after being around a lot of fire and seeing what it can do in a majestic way.

Randy Dotinga is a Monitor contributor.