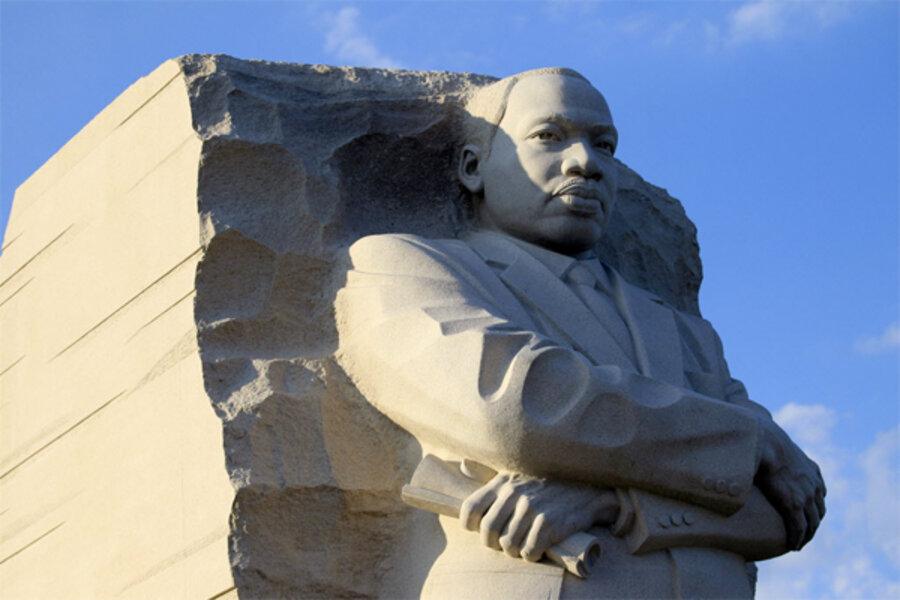

Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial and the danger of the misquote

In advance of the official date of the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington, workers scrambled to complete refinishing part of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial in Washington where a disputed inscription was recently removed. The repair job is a vivid reminder of the problems that can result from not getting a quote just right. It’s a lesson worth remembering for authors who must use quotation in their work.

The King monument included a paraphrase that read: “I was a drum major for justice, peace and righteousness.” Here’s what King actually said: “Yes, if you want to say that I was a drum major, say that I was a drum major for justice. Say that I was a drum major for peace. I was a drum major for righteousness. And all of the other things will not matter.”

Critics of the paraphrase argued that it made King sound egotistical, while his original quote was much more self-effacing. The paraphrase also lacks the appealing rhythm of King’s rhetoric, which had been refined by his years in the pulpit.

It’s easy for most of us to see that this mangling of King’s words was wrong-headed, but the larger lesson is that this kind of misquotation goes on all the time, most visibly in the work of sloppy writers and researchers. Thanks to the Internet, misquotation tends to spread more widely than it once did, becoming rooted in the popular discourse and taking on a life of its own.

Just ask Martha White, the granddaughter of the late author and essayist E.B. White, who compiled “In The Words of E.B. White,” a collection of her grandfather’s most memorable quotations. Part of her motivation for the project was the opportunity to correct the E.B. White misquotes frequently found on the Internet and in public presentations. “Quotations have a way of shape-shifting, and like the best shape-shifters in mythology or fairytales, they can unexpectedly take on the characteristics of the work entirely,” Martha White wrote in an essay on the phenomenon.

As a case in point, she mentioned this ersatz E.B. White quote that spanned a lecture screen at 2011 Harvard Business School Conference: “I get up every morning determined both to change the world and to have one hell of a good time. Sometimes this makes planning the day difficult.”

Here are E.B. White’s actual words: “If the world were merely seductive, that would be easy. If it were merely challenging, that would be no problem. But I arise in the morning torn between a desire to improve (or save) the world and a desire to enjoy (or savor) the world. This makes it hard to plan the day.”

To the casual reader, the basic sense of these quotes seems the same, but only the original conveys the careful way that White’s mind worked. The misquote expresses flippancy, while White’s real words capture his sublime method for sorting his way toward a small truth.

Such examples underscore why journalists and historians have a special obligation to quote their subjects correctly. But accurate quotation isn’t always a clear-cut matter of right versus wrong, as I discovered when I wrote a book about a pivotal season in the life of John James Audubon. English was a second language for Audubon, who grew up as a Frenchman, and his journals are thick with misspellings and grammatical lapses than can make his words tough sledding for the general reader.

In the interest of clarity, I usually cleaned up these mistakes when quoting Audubon, assuming that the famous bird artist obviously wrote in order to be understood, and that he would certainly agree with my editorial assistance.

But Audubon scholar Christoph Irmscher, who read a first draft of my manuscript, noted that Audubon’s imperfect English was an important part of his immigrant identity. Was I sanitizing this reality, even with the best of intentions?

I hit upon a compromise, retaining my edits to keep Audubon’s observations more readable, but including a note in my text alerting readers to what I had done, then referring them to the source material I had used in case they wanted to encounter Audubon in his unaltered form.

My dilemma points to a common challenge faced by journalists and other writers of nonfiction. Novelists and short story writers can have their characters say whatever the author wants. We nonfiction writers also like to shape our work to tell a compelling story. But in using quotation, we have to remember that we don’t get to choose what our subjects say; they do.

Danny Heitman, a columnist for The Advocate in Baton Rouge, is the author of A Summer of Birds: John James Audubon at Oakley House.